Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

22 Sep, 2021

|

Workers install solar panels on a home in California. The Solar Energy Industries Association said thousands of jobs could be lost if the Commerce Department imposes tariffs on cells and panels imported from Southeast Asia by some of the world's biggest manufacturers. |

The latest feud over trade policy in the U.S. solar industry comes at a critical moment for President Joe Biden, who hopes to turn the country into a leading manufacturer of green energy technology while ensuring that efforts to limit climate change are not hamstrung by soaring prices or equipment shortages.

The push for tighter trade restrictions once again pits solar manufacturers demanding more protection from foreign competition against some of the country's biggest project developers, who warn that raising import costs will threaten growth.

The conflict heated up three months before international climate negotiations in November and as the Biden administration faces a high-wire act in Congress, with Democrats trying to hold together the moderate and progressive wings of their caucus behind a massive spending bill that would advance many of the president's policy objectives.

The U.S. Department of Commerce is expected to initiate an October investigation into allegations that Chinese manufacturers have "unlawfully" avoided import taxes by moving some production to Southeast Asia. The claim was brought by a group of unnamed companies that have called for antidumping and countervailing duties on Chinese solar products to be expanded to cells and panels imported from Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam by some of the world's biggest manufacturers.

The Solar Energy Industries Association, or SEIA, said Sept. 22 that the requested tariffs are "massive" and would put at risk nearly 30% of the solar capacity that is expected to be installed through 2023.

"Our nation's ability to effectively address climate change and fuel sustained economic growth relies on rapid deployment of solar and clean energy in the next 2-3 years," the group said in a letter to Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo that was signed by 200 companies. "The petitions put this growth at severe risk and threaten the livelihoods of more than 230,000 American solar workers."

The Commerce Department investigation is likely to be followed in January by an extension of another set of tariffs that were imposed in 2018 on most imported solar cells and panels, analysts at Roth Capital Partners LLC said in a Sept. 16 research note.

Adding to the concerns of project developers, equipment orders have been hung up at American ports as U.S. Customs and Border Protection, or CBP, started detaining imports linked to alleged labor abuses.

Perfect storm of trade problems

The current set of trade issues poses unprecedented challenges for the domestic solar market, John Magnus, president of TradeWins LLC, a trade law and policy consulting firm, said on a Sept. 15 conference call hosted by Roth.

"Each one in a normal time would be a major trade policy challenge for an administration, and Biden has them all on his plate simultaneously," said Thomas Prusa, an economics professor at Rutgers University who has testified before the U.S. International Trade Commission, or USITC, on behalf of SEIA. "How this works out will be a major test for their commitment to green energy."

Tariff proponents have dismissed SEIA's warnings, pointing to a report the group recently published in which analysts raised their growth projection for the U.S. solar market through 2026.

"Clearly, there are certain parts of the industry that benefit from the status quo and being able to import stuff from China that's made on the cheap," said Nick Iacovella, communications director for the Coalition for a Prosperous America, which represents manufacturers including First Solar Inc. "[But] I don't think that [solar] demand is going anywhere except for up."

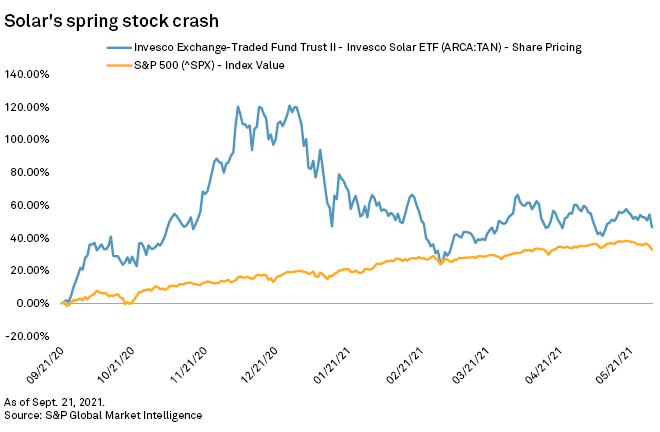

The solar industry roared into 2021 amid record growth forecasts and new commitments from governments and businesses to limit climate change. By spring, investors had begun to doubt whether the industry could deliver projects profitably and on time as prices for key raw materials rose and COVID-19 upended global supply chains.

Then, over the course of two months this summer, the trade problems came to a head.

'Administration is in a bind'

In June, CBP said it would begin detaining imports that contain material from Hoshine Silicon Industry Co. Ltd., a leading raw-material supplier to the solar industry. The U.S. government said it obtained evidence that workers at Hoshine factories in China's Xinjiang region were threatened, intimidated and denied freedom of movement.

"The administration is in a bind," Stacy Ettinger, a partner at K&L Gates LLP who focuses on international trade, said on Roth's September call. "... [There's] no way to sort of meet the requirements in terms of what data to provide or what information to provide in terms of tracing … the products back to the mining activity in Xinjiang."

The Chinese government denies allegations of forced labor. Neither the Chinese Embassy in Washington nor Hoshine responded to messages seeking comment.

In August, manufacturers Auxin Solar Inc. and Suniva Inc. asked the USITC to recommend that Biden extend tariffs that former President Donald Trump imposed on most imported solar cells and panels in 2018.

Days later, Commerce Department officials met with representatives of First Solar, Q.Cells North America and LG Electronics USA to discuss how tariffs on Chinese imports were affecting business. The companies logged in to a videoconference Aug. 11 as members of the American Alliance for Solar Manufacturing, which has accused Chinese firms of selling cells and panels at below market value despite antidumping and countervailing duties that Washington imposed on Chinese imports in 2012.

Also on the call was Timothy Brightbill, a partner at Wiley Rein LLP and lawyer for the alliance who has been at the center of the solar industry's long-running trade feud. Shortly after the meeting, Brightbill filed a petition with the Commerce Department on behalf of unnamed companies seeking to expand Chinese tariffs to some manufacturers in Southeast Asia.

Fearing retaliation, the group — American Solar Manufacturers Against Chinese Circumvention, or A-SMACC — is trying to keep its members' identities a secret. The demand for anonymity has outraged domestic project developers.

Brightbill said in an email that China's dominance of the solar supply chain has given Beijing and the country's manufacturers "much greater" ability to retaliate than they had in previous trade bouts. "For this reason alone, the companies' identities are entitled to proprietary treatment under Commerce's regulations," Brightbill said.

Brightbill said Chinese manufacturers' alleged circumvention of tariffs "was not a focus of the discussion" during the meeting between the American Alliance for Solar Manufacturing and the Commerce Department.

Asked whether LG is an A-SMACC member, John Taylor, a senior vice president at the company, said in an email, "Our participation in some activities should in no way imply participation in others. To insinuate as much would be false."

Q.Cells did not respond to a message seeking comment. First Solar declined to comment about A-SMACC.

|

President Joe Biden, shown here at the United Nations General Assembly on Sept. 21, entered office with economic and climate strategies that rest, in part, on domestically manufacturing more of the products the world needs to reduce carbon emissions. |

Trade tension has staying power

For U.S. solar companies fighting the latest round of tariff requests, further supply chain disruptions may be unavoidable.

If, as expected, the Commerce Department opens an investigation of A-SMACC's claims, that could be enough to shut down imports from companies listed in the complaint since the tariffs could be applied retroactively, Roth analysts said.

Both sides agree that tariffs alone are not enough to support U.S. manufacturers up and down the solar supply chain. The Democrats' reconciliation package, which is being negotiated in the House of Representatives, includes provisions to incentivize clean-energy manufacturing, but a tax credit that U.S. producers say is crucial to attracting and supporting an entire supply chain is in doubt.

The credit proposed in the Solar Energy Manufacturing for America Act is the right design, Rhone Resch, president of Solarlytics and SEIA's former president and CEO, said on Roth's investor call. "So, I think they're going to push pretty strong for it," Resch noted.

With moderate Democrats pushing to trim the package's $3.5 trillion price tag, however, Resch said the solar industry has other, more urgent priorities than creating a new manufacturing incentive.

In an industry where most jobs are in project development, lobbying efforts have long focused on incentivizing construction. That approach, some argue, is the best way to attract manufacturing over the long term.

"Nobody has ever built a manufacturing market of any note without being one of the top couple of dominant demand players," said Neal Dikeman, a partner at Energy Transition Ventures LLC. "And the second condition is, your companies have to get to scale, and they have to continue to remove costs at several percent a year, every year, until the end of time."

The U.S. is already a top solar market, but after years of tariffs, the country still does not make enough solar panels — or their underlying materials and components — to meet domestic demand.

In a recent report, the Department of Energy said there are cost advantages in manufacturing outside of the U.S. due to "different labor standards and regulations abroad."

Increasing automation can help American producers compete, the DOE said, as can government policies.

"It's clear what needs to be done" to create a domestic solar supply chain, Rutgers University's Prusa said. "The question is whether the incentives, financial incentives, are enough, because the capital investments are so high."

If the U.S. fails, Prusa added, these type of trade tensions could easily continue for not just the next three or four years but for the next 20 years.