Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

25 Aug, 2021

|

Container ships at the Port of Los Angeles, with the Port of Long Beach in the distance. An import restriction on Hoshine Silicon Industry Co. Ltd., a major raw-material supplier to the solar industry, is disrupting the flow of equipment to the U.S. market. |

America's leading solar lobby wants the U.S. government to change how it enforces a ban on imports linked to alleged labor abuses as the trade group tries to contain the fallout from a recent crackdown.

George Hershman, president of Swinerton Renewable Energy and chair of the Solar Energy Industries Association trade group, said in an interview that solar panel importers should be required to document their supply chains back to polysilicon producers rather than having to account for raw-material suppliers further upstream.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, or CBP, should deprioritize enforcement for importers that meet that standard through audited tracing programs — and that can show they adhere to corporate responsibility codes of conduct — the solar group says.

The organization, which has spent $830,000 this year lobbying on various issues, according to OpenSecrets.org, is having "ongoing discussions with the government about our proposal," said John Smirnow, the group's general counsel and vice president of market strategy.

"We're not saying 'stop enforcement,'" Smirnow said. "As Customs looks at 100 importers of solar panels, if 50 of those can establish that they meet these ... principles, then set them aside in Customs enforcement targeting and focus on the companies who aren't able to establish a verifiable commitment" to eliminating forced labor.

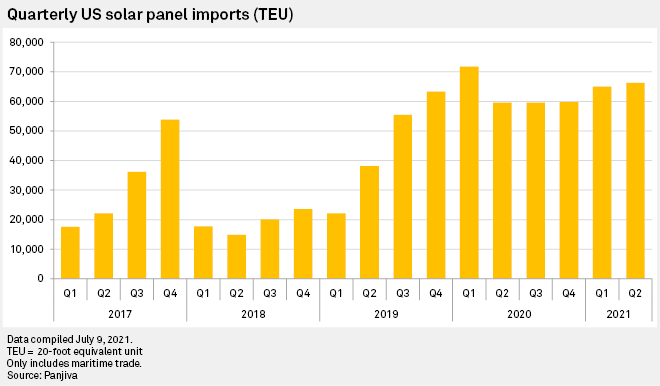

The U.S. solar industry has been hit by a wave of detentions since CBP said in June that it would begin stopping imports that contain material from Hoshine Silicon Industry Co. Ltd. and its subsidiaries. CBP said it had evidence that workers at Hoshine factories in China's autonomous Xinjiang region were subjected to threats and intimidation and were denied freedom of movement. Beijing denied allegations of forced labor.

Hoshine supplies silicon metal to some of the world's biggest producers of polysilicon, a key ingredient in most solar panels, according to analysts.

The detentions are disrupting the flow of equipment to the U.S. solar market, creating "big challenges" for project developers, Hershman said.

"There is more opportunity now than ever" to grow America's solar sector with the support of a presidential administration and business community that have prioritized investments in green energy to limit climate change, Hershman said. "We don't have the time to waste on these issues."

Analysts at ROTH Capital Partners LLC said it could be a year before the industry is able to document the origin of the silicon metal in an individual solar panel. Detentions so far have jeopardized more than $2 billion of solar project investments, the analysts said in a research note Aug. 21.

Hoshine did not respond to messages seeking comment.

A spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington, Liu Pengyu, said in a statement that allegations of forced labor in Xinjiang are "a flat-out lie."

"Restricting Chinese products because of a lie violates international trade rules and market principles, and undermines global industrial and supply chains," the statement said. "Bashing Xinjiang's photovoltaic industry will not only hurt the clean energy industry in China and the U.S. but also undermine our joint efforts to deal with climate change."

The White House did not respond to a request for comment.

"U.S. importers have a responsibility to exercise reasonable care and to ensure that their supply chains are free of forced labor," a CBP spokesperson said in an email, citing the 1993 Customs Modernization Act.

'Casting a broad net'

In the two months since CBP said it would target imports linked to Hoshine, the agency has acknowledged "casting a broad net into their detentions," Richard Mojica, a Customs expert at Miller & Chevalier Chartered, said Aug. 19 on a conference call hosted by ROTH.

"CBP is requesting unprecedented cooperation from upstream suppliers," Mojica said. "I think as the situation becomes bigger, as more companies report detentions and as more developers are also vocal about these detentions, the Biden administration will have to act."

"I think Customs actually has flexibility to change its enforcement so that it matches … what is commercially reasonable while also achieving the goals of ensuring that there is no forced labor," Mojica added. "Modifying the enforcement does not necessarily mean not caring about forced labor. It just means that, at the moment, CBP is taking a very aggressive approach to detaining everything."

Mojica did not respond to a message seeking comment on the changes proposed by the Solar Energy Industries Association.

Mark Widmar, CEO of First Solar Inc., a U.S. manufacturer that is not exposed to China's polysilicon industry, criticized efforts aimed at "selectively sanitizing the solar supply chain."

"It's unfortunate that some find themselves painted into a corner due to their over-reliance on China's solar industry, which has proven to be an unreliable and risky partner on multiple accounts," Widmar said in an emailed statement. "And it's disappointing if they are now essentially advocating against holding China's solar industry accountable for possible human rights violations at stages of its supply chain that are most vulnerable to abuse and the hardest to audit."

Smirnow said that because most of the silicon metal produced in Xinjiang is used by polysilicon plants in the region, proving that a solar panel is free of Xinjiang polysilicon "is going to dramatically lower the risk of forced labor in the solar supply chain."

Elise Shibles, a Customs and trade lawyer at Sandler Travis & Rosenberg PA and former import specialist at CBP, said on the ROTH call that CBP has a "very high bar" for the amount of evidence necessary to prove goods were not made with forced labor. "I have not seen them modify their approach to make it easier to respond to these detentions," Shibles said.

Shibles said it is unclear whether the White House would intervene on behalf of the solar industry in this case since the Biden administration said it will not compromise on human rights issues in order to achieve its climate goals.

"The environmental goals are a priority for this administration," U.S. Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said at a June news conference announcing the import restriction on Hoshine. However, "our environmental goals will not be achieved on the backs of human beings in a forced-labor environment."

At the same event, CBP Executive Director Ana Hinojosa said the agency is "trying to be very responsible in ensuring that we don't unintentionally stop legitimate trade [for which] we don't have a clear connection to" Hoshine or alleged labor abuses.

Earlier this year, the Solar Energy Industries Association published guidance to help companies trace their international supply chains. While the industry's initial efforts to avoid potential labor abuses focused on polysilicon suppliers, companies that follow the tracing guidance also would be able to "show where the silicon metal comes from," Smirnow said in June.

However, getting visibility that deep into the solar supply chain is proving difficult.

The silicon metal market "is a little more convoluted, and it's not quite as straightforward" as other parts of solar supply chain, Andy Klump, CEO of the China-based consulting firm Clean Energy Associates LLC, said on the ROTH call.

Klump said it is difficult to say how long it will take the solar industry to trace silicon metal, but "I don't think it takes six or 12 months. I think it's just a question of [manufacturers] having the motivation" to comply with auditing programs.

Hershman said companies in the U.S. urgently need a resolution to the risk and uncertainty in the market or "investment capital will go elsewhere."

"Time is not on our side on this," Hershman said.