Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

4 May, 2021

By Brian Scheid

Inflation is on track to rise to levels not seen in 14 years and the Federal Reserve is betting heavily that the stay at these heights will be brief.

But if this substantial jump is not temporary, or "transitory" as Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has frequently said, the consequences could be dire for the domestic economy's post-pandemic rebound, analysts said.

If rising inflation has staying power, bond and equity markets could be upended, consumer spending may collapse and, as the U.S. slips further into a recession, the Fed might be forced to end $120 billion in monthly bond purchases and hike interest rates far earlier than anyone expected.

"The risk is that you end up behind the curve and you have to tighten policy more quickly than you'd prefer," said Michael Pugliese, an economist at Wells Fargo Securities, in an interview. "It would be a sharp, sudden slamming on the brakes."

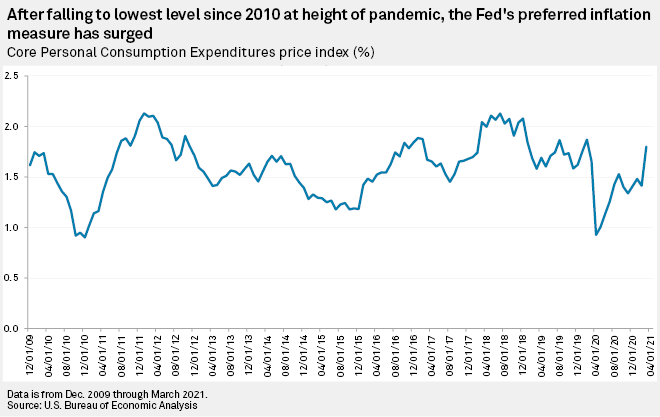

On April 30, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that the core personal consumption expenditure price index, the Fed's preferred measure of inflation, hit 1.8% in March 2021, compared to the same month a year earlier, when the majority of U.S. pandemic lockdowns began. The index, also known as core PCE, was up from 1.4% in February 2021.

The figures still lag the Fed's long-term target of core PCE inflation above 2%. In a May 1 note, economists with Goldman Sachs said they expect core PCE to exceed 2.4% in April, the highest year-over-year increase since February 2007 when the figure was at 2.5%.

Powell, and many others, attribute the anticipated increase to base effects, or the extreme difference created when comparing economic data from the height of the pandemic, and current bottlenecks in the global supply chain.

Supply shortages

"Right now, demand has picked up, but supply is not available for many things," said Kathy Jones, senior vice president and chief fixed-income strategist at the Schwab Center for Financial Research.

Shortages of everything from computer chips to copper have upended markets, causing a surge in global demand and a spike in inflation.

"There's going to be this lag because some things can't just pop out of the woodwork right away," Jones said in an interview. "The feeling at the Fed is that we're getting this demand surge, supply has not caught up. But they'll soon find an equilibrium and go back."

But the question of how soon looms large over global markets and has raised concerns that Fed officials are discounting the risk sustained inflation poses to the rebound.

James Knightley, ING's chief international economist, said the ongoing supply capacity shortages in the U.S. may be a signal that "inflation pressures could be more sustained than the Fed is publicly admitting," he wrote in an April 29 note.

"The Fed remains comfortable playing the biggest game of 'chicken' with inflation that any of us have ever seen," said Tom Essaye, a trader and founder of financial research firm The Sevens Report, in an April 29 note. "And, they better be right, because if they are wrong about inflation being transitory, then the end of 2021 [and] start of 2022 could be very painful."

Lagging employment

The Fed has signaled it will not deviate from its loose monetary policy until its employment and inflation goals have been met, objectives Powell has not defined in order to give the central bank flexibility going forward.

Employment, which still lags its pre-pandemic level by 8.4 million jobs, needs to see multiple months of million-job growth before Fed officials earnestly begin discussions of tapering bond purchase, analysts said.

During an April 28 press conference, Powell dismissed concerns that inflation could continue to rise without a corresponding increase in employment.

"It seems unlikely, frankly, that we would see inflation moving up in a persistent way that would actually move inflation expectations up, while there was still significant slack in the labor market," Powell said.

Since 2007, wages have not kept pace with the Fed's inflation and productivity targets. Average hourly earnings in March hit $29.96 per hour in March, compared to the Fed's goal of $33.41 per hour, a $3.45 per hour difference. The gap is the widest since March 2020 when it was a differential of $3.54 per hour.

That gap between wages and Fed targets

If inflation continues to climb "consumers have to be able to absorb higher prices and that's hard to do unless wages keep up," she said. "If inflation accelerates but wages don't, purchasing power will get squeezed causing demand destruction."

Inflation has risen largely due to fiscal injections into the domestic economy, particularly stimulus checks, she said.

"So, once the last round of checks is spent, employment will once again become the dominant driver of income and spending," Markowska said.

Wage growth

But wages may increase faster than the Fed expects, according to Andreas Steno Larsen, global chief strategist with Nordea Bank.

U.S. workers are in a far better position to negotiate wages with employers due to lowered labor mobility caused by border closures and COVID-19 fears, Larsen said in an interview. In addition, stimulus checks and expanded unemployment benefits during the pandemic have contributed to an inability for employers to hire new workers for lower-paying positions.

"We may see wage growth coming along much earlier than in previous cycles, which could turn out to be a big surprise for the Federal Reserve," Larsen said.

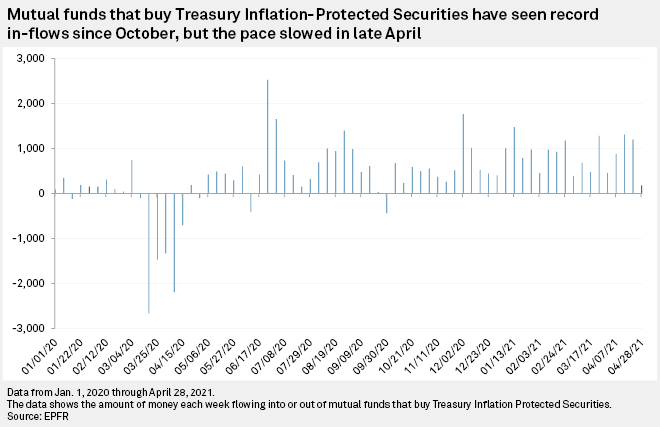

Expectations for sharply higher inflation have caused a surge of investors to pour billions in inflation-protected government bonds.

Since the start of August, roughly $22.5 billion has flowed into mutual funds that buy Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS, according to EPFR, which tracks fund flows and allocations. Funds that buy the bonds have seen 30 straight weeks of inflows, the most in over a decade.

But the rise in inflation-protected investments may have peaked, possibly due to the Fed's repeated assurances that inflation increases were only temporary.

After averaging nearly $1.13 billion for the first three weeks of April, just $184 million flowed into mutual funds that buy TIPS during the last week of April, according to EPFR's latest data.

According to Jones with Schwab, the U.S. economic recovery is now being guided by a Fed willing to tolerate higher inflation and fiscal policies focused on stimulus aimed at boosting spending from lower-income households. This view will likely lead to inflation between 2% and 3% in the near future. Core PCE has not averaged above 2% since April 2012.

"We know that central banks have the ability to squash inflation, right now it's the willingness to do it," Jones said. "If, indeed, they have miscalculated and it looks like this inflation is going to be more long-lasting then they'll probably have to play a game of catch up."