Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

27 Sep, 2021

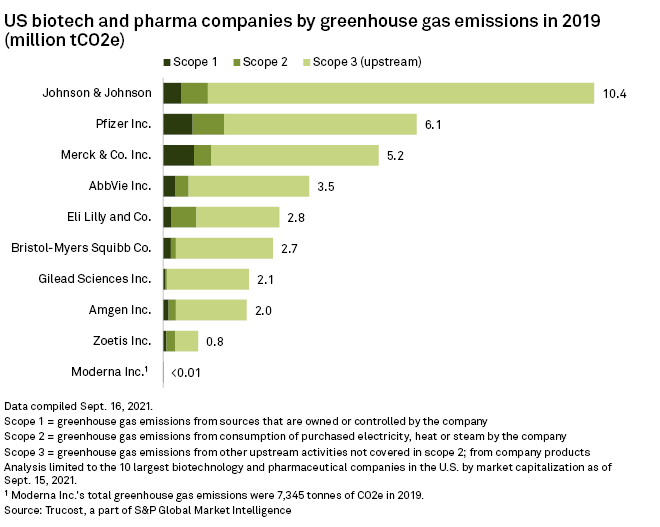

The largest U.S. drugmakers have all committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the near term as a global economic forum drew attention back to the sector's growing carbon footprint.

The healthcare sector overall contributes 4.4% of global emissions. As one of the fastest-growing industries in the world — in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic — that footprint is forecast to triple by 2050 if left unchecked, COP25 High Level Climate Champion Gonzalo Muñoz told delegates at the World Economic Forum's Sustainable Development Impact Summit on Sept 22.

But biopharmaceutical companies, along with medical technology developers, have taken a step forward in their commitments to reach carbon neutrality, said Muñoz, pointing out that 28% of the sector by revenue has joined the United Nations' Race to Zero commitment to reach net-zero carbon emissions by midcentury. Investor pressure is driving some of these actions.

"These ESG topics are far from being extracurriculars or distractions — these are part of the value-making process, and that's what we've heard from investors," Jim Greffet, head of environmental, social and governance strategy at Eli Lilly and Co., said in an interview.

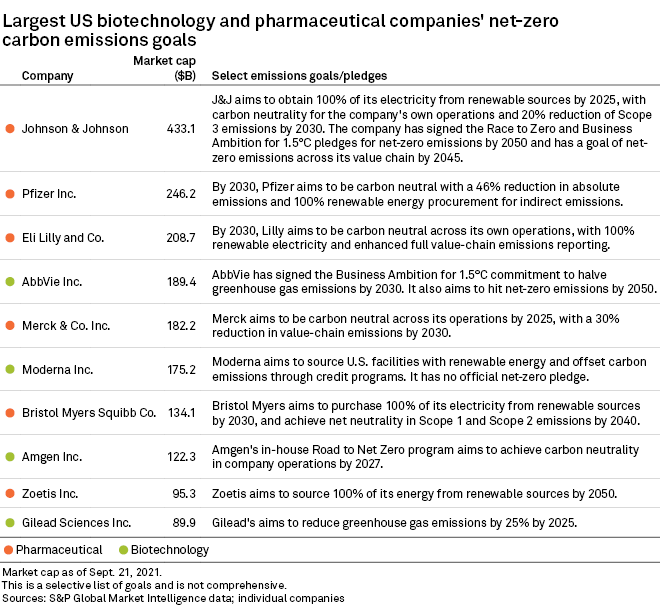

Johnson & Johnson is seen as one of the leaders in environmental stewardship among its U.S. peers, according to the environmental nonprofit Health Care Without Harm. Half of the electricity the company uses already comes from renewable sources, and J&J has committed to reaching 100% by 2025. The pharmaceutical giant has also set a goal of net-zero emissions across its vast supply chain by 2045.

Other drugmakers have invested in renewables as part of a push toward net-zero. Merck & Co. Inc. has secured several contracts with wind and solar power providers to accelerate its own goal of 100% renewable energy by 2025, while Lilly entered a joint venture with Enerpower in July to open the largest solar farm in Ireland, which will power its nearby drug manufacturing plant.

But the top U.S. pharmaceutical companies have fallen behind their European counterparts in making commitments and acting on them, with the likes of the U.K.'s GlaxoSmithKline PLC and AstraZeneca PLC, Denmark's Novo Nordisk A/S and Switzerland's Novartis AG years ahead, said Health Care Without Harm's international climate policy Director Sonia Roschnik.

Roschnik, formerly director of the Sustainable Development Unit of England's National Health Service, placed the blame partially on the timing of politics, pointing out that the U.K. has had climate change legislation in place since 2008.

"The U.S. is only just coming back into the discussion again," Roschnik said in an interview. "My sense, though, is that in this catch-up the U.S. has got some shining examples, certainly in terms of healthcare institutions that are wanting to push play and wanting to push their supply chain. So I suspect it won't be long before a whole load more are party to that."

Putting technology to use

One of the long-time environmental leaders on the U.S. side is Amgen Inc., which has reduced carbon emissions by 33% since the drugmaker began its environmental sustainability program in 2008. The Thousand Oaks, Calif.-based company has not joined the global pledges for net-zero emissions but now has an in-house goal called Road to Net Zero to achieve carbon neutrality in its own operations — which cover Scope 1 and 2 emissions — by 2027.

|

|

"The importance of having done this since 2008 is that it set a path where we've been reducing our footprint since then," Jim Weidner, executive director of Amgen's Engineering Technical Authority division, said in an interview. "So when we started doing our Road to Net Zero in 2020, we're building on successes we've had in the past to reduce our carbon as well as waste and water footprints."

The process of developing new medicines can in itself be a major drain on resources and require massive amounts of energy, Fanny Yuen, principal scientist of nonprofit Green Your Lab, told S&P Global Market Intelligence.

"The huge carbon footprint starts in the drug discovery and drug development phase — the lab procedures are complex, unforgiving, and both time and resource consuming," Yuen said. Given the low success rates of clinical trials, pharmaceutical companies do not want to invest in the sustainability of a new drug before it has gone to market, Yuen added.

The strict regulatory approval regime for medicines means it is tricky to change manufacturing processes even if the end result is reducing the carbon footprint, Yuen said.

Amgen has tried to tackle this problem by developing new ways to manufacture biologic drugs, which are derived from cells and produced under controlled conditions in bioreactors.

While traditional methods of manufacturing biologics like Amgen's blockbuster arthritis treatment Enbrel require 20,000-liter bioreactors, high-yielding cell lines allow Amgen's Singapore site to use 2,000-liter bioreactors to produce the same amount of product, Weidner said. The result is a 73% reduction in energy consumption and a 69% reduction in carbon footprint compared to a typical manufacturing plant. More planned facilities in Ohio and North Carolina will be built with a reduced carbon footprint in mind.

Lilly, which makes large biologics such as monoclonal antibodies to treat COVID-19 as well as other infectious diseases, has also been overhauling its manufacturing processes.

"We can produce the same quantity and quality of medicine, but using a smaller footprint, smaller plant, smaller energy consumption and smaller impact on the physical environment by making the process more efficient," Lilly's Greffet said.

Beyond Scope 1 and 2 emissions, which cover a company's own operations, a third scope of a company's carbon footprint are the suppliers and external operations across their supply network.

With large, international supply chains, drugmakers can find these emission goals harder to track, requiring management and lengthy monitoring, Lilly's Greffet said. "We need to get our arms around what it is, and there are reasons why it's more challenging."

Lilly is a major manufacturer of insulin, for example, which requires low temperatures during transport and has historically been moved by air. An early success for the company was to build temperature-stable containers needed for sea shipment, cutting carbon emissions on the logistical side in half, Greffet said.

As part of its own plan to reduce Scope 3 emissions, Amgen now assesses the sustainability of new suppliers before contracting them, Weidner said.

Carbon collaboration

The similarity between Amgen and Lilly's carbon strategies reflects a more collaborative attitude than is typically seen across the pharmaceutical industry, Greffet noted.

Health Care Without Harm's Roschnik agrees that there is a "common enemy" approach to collaborating in the face of the climate crisis, particularly between drugmakers and healthcare providers.

"My hope is that by actually everybody working on this agenda together, we could sort of recognize that we're all in the same boat," Roschnik said. "And some of the best solutions might be where you come up with a product that suits your needs — it's identified across [the industry] and that's an innovation for the future.