S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

15 Sep, 2021

By Brian Scheid

New vehicle prices have jumped by record highs as a global semiconductor shortage has dropped inventories to historic lows.

Source: Monty Rakusen/Image Source via Getty Images

On a typical day, the Monroeville, Pa., Kia dealership has about 150 new sedans, SUVs and sports cars on its lot just outside Pittsburgh.

"Right now, we have 14," Jeff Iwanowski, the dealership's executive general manager, said in a Sept. 14 interview.

Faced with a global shortage of semiconductors and other needed parts, dealerships like Iwanowski's are facing a historic inventory shortage as demand for new cars climbs from pandemic lows. Cars are selling before they are even taken off delivery trucks, dealers are paying as much as $10,000 over retail prices at auction, and Iwanowski and other dealers have few options but to wait for supply to rebound.

"Demand is exceeding supply ... so we've had to become better at our job," Iwanowski said.

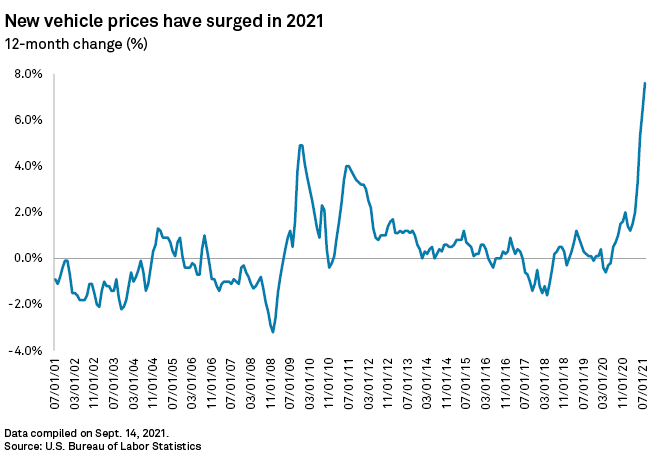

On Sept. 14, the U.S. Labor Department reported that new vehicle prices in August climbed 7.6% from 12 months earlier, the largest annual percentage increase in more than 40 years. New vehicle prices have climbed an average of 3.4% each month from December 2020 through August 2021 and have not declined on a year-on-year basis since June 2020, the data shows.

According to Kelley Blue Book, the average price of a new vehicle hit an all-time high of $43,355 in August, an increase of 10% from a year ago.

Prices are expected to continue to soar, economists said.

"Demand is strong and there is no supply, so consequently there are none of the usual discounts to be had on a list price, meaning prices are up on last year," said James Knightley, chief international economist with ING. "Unfortunately, I don't see things easing up quickly."

Low volumes

Despite healthy demand, total automobile sales in August were just below 1.1 million, the lowest volume since the height of the pandemic in April 2020 and among the lowest monthly totals in roughly 10 years, according to Kelley Blue Book. An average of 1.4 million vehicles were sold each month in 2019, according to data from Cox Automotive, the parent company of Kelley Blue Book.

"With the ongoing inventory challenges that auto manufacturers are facing across the board, coupled with historically low incentive spending, car shoppers end up being the ones paying the price, quite literally," Kayla Reynolds, an analyst for Cox Automotive, said in a Sept. 14 note.

Dealerships tend to want to average 60 to 70 days worth of new vehicles on their lots, but the national average by the start of August was just over 30 days, according to Cox Automotive data.

The dearth of supply stems from a shortage of semiconductors, or microchips, which, among multiple other uses, powers a new car's onboard computer system.

Pat Gelsinger, Intel Corp.'s chief executive, has warned that the shortage could persist well into 2023 and several automakers have slowed or halted production in response.

In early September, General Motors Co. and Ford Motor Co. idled nearly all their North American assembly plants. Meanwhile, Nissan Motor Co. Ltd. shut down its manufacturing complex in Tennessee and Toyota announced it was slashing its production for September and October by about 40% each month.

But supply-side challenges extend beyond the chip shortage and now include shortages and high prices for some raw materials, hiring obstacles, and shipping delays, particularly for ocean freight, said Oren Klachkin, lead economist with Oxford Economics.

Those issues will likely drag on as COVID-19 and its variants continue to spread, Klachkin said.

"We do anticipate these headwinds to start very slowly dissipating over the coming months, but it will take a considerable amount of time to fully clear the backlogs," Klachkin said.

Driving inflation up

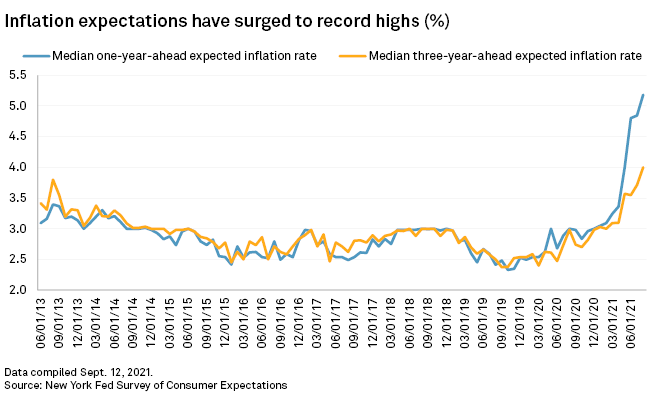

The rise in new vehicle prices has contributed to the ongoing rise in inflation.

In its August Survey of Consumer Expectations, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York said consumers expect inflation to climb 5.2% a year from now, up from 4.8% in July. Consumers see inflation to be at 4% in three years, up from the 3.7% they expected a month ago.

The U.S. Labor Department reported Sept. 14 that its consumer price index, the market's preferred inflation metric, rose 5.3% year over year in August.

New vehicle prices have a relatively limited impact on the index, accounting for about 3.8% of the index's weight, compared to food, which has 13.9% weight, or shelter, which accounts for 32.6% of the index's total weight.

Still, new vehicle prices are impacting used car and truck prices, which have seen a record increase this year and may not lessen due to the ongoing supply shortage for new vehicles.

"With inventories at record lows relative to sales, new vehicles prices are likely to continue to climb higher, which will limit how much ground used car prices end up giving back in the coming months," said Sarah House, a senior economist with Wells Fargo.

Together, used and new vehicle prices account for about 7.3% of the index's total weight. Used car and truck prices were up nearly 42% in July from a year earlier, but seem to have peaked, falling to under a 32% increase in August from a year earlier.

Falling used car prices, along with declines in other prices, such as airline fares, may signal that the rise in inflation may be short-lived, said Augustine Faucher, chief economist of The PNC Financial Services Group.

"Overall I think inflationary pressures are easing, despite the increase in new car prices," Faucher said. "In addition, new car prices will eventually come down as supply chains normalize and production picks back up, and the higher prices discourage some sales."

The demand for new cars may ease as car rental firms, which off-loaded their stocks during the pandemic, slow their frenzied buying and overall demand dips into the winter, Knightley with ING said.

"Consequently, I think we may see the intensity of price pressures in this component start to moderate a little, but I think we are a long way off any possible price declines," Knightley said. "In the meantime, price pressures are building elsewhere as companies increasingly feel able to pass higher costs onto customers."