Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

31 May, 2023

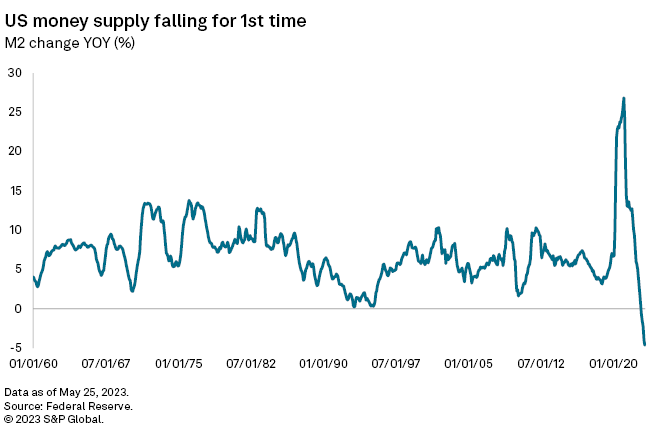

The supply of money in the US economy is dropping at the fastest rate ever, potentially helping slow stubbornly high inflation.

Cash, personal savings and market accounts accessible to consumers — collectively referred to as the "M2" money supply — fell to $20.673 trillion in April, a drop of $1.031 trillion from a peak in July 2022, according to the latest Federal Reserve data. On a year-over-year basis, the 4.6% drop in April 2023 is the largest decline since the Fed began formally tracking M2 in 1959.

The unprecedented decline in M2 is being fueled by the Fed's aggressive monetary policy tightening, including lifting interest rates from near zero to over 5% since March 2022, a decline in credit availability, turmoil in the banking sector and the end of COVID-19 government stimulus efforts. The pullback leaves consumers with less cash to spend on goods and services, which may help further pull inflation from its current highs, and is fueling nascent but growing fears that prices will soon start to fall.

"The decline in the M2 money supply means that inflation is likely to fall over time," said Steven Anastasiou, an economist at Economics Uncovered, in an interview.

M2 decline

Much of the fall in M2 is due to the end of the federal government's efforts to prop up the economy during the pandemic by pumping in trillions of dollars through stimulus checks and loans. From March 2020 to the peak in July 2022, the M2 supply increased by $5.725 trillion.

M2's fall is additionally being driven by not only a decline in savings rates but also the ways Americans are saving their money. The highest interest rates since 2007 have motivated savers to move billions of dollars from demand deposits, or money in bank accounts that can be withdrawn at any time, to time deposits, which are interest-bearing accounts with maturity dates, such as certificates of deposit.

Small-denomination time deposits, those with balances of less than $100,000, have increased by more than 18 times over the past year, rising from $36.6 billion in April 2022 to $674.8 billion in April 2023, according to Fed data. Large time deposits, which are not included in M2, have increased by about $417 billion over that stretch, a nearly 29% increase in a year.

This is all money that cannot be immediately spent, effectively slowing consumer spending and curbing inflation growth, said Donald Luskin, chief investment officer for Trend Macrolytics, in an interview.

Nudging inflation down

As long as M2 is in decline, inflation will likely be as well.

Personal consumption expenditures excluding food and energy — the "core" inflation the Fed is trying to bring down to 2% — increased 4.7% from April 2022 to April 2023, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported May 26. This was up from the 4.6% yearly increase in core inflation in March, but below the peak of 5.4% in annual growth, reached in February 2022.

Though it is contributing to the pullback in inflation, M2's fall likely will not last that long, said Lyn Alden, a macroeconomist and independent investment strategist.

"The Fed can probably maintain destruction of M2 for another quarter or two, but the longer it goes on, the harder it gets," Alden said. "Such highly indebted systems have trouble maintaining sustained destruction of money, but it can be done for periods of time."

If the broad money supply is not rising, then asset prices are unlikely to rise as well, causing federal tax receipts to stagnate and the fiscal deficit to widen, Alden said. In order to address that growing deficit, the government will likely issue a lot more bonds, which will increase M2.

M2 remains $5.223 trillion above where it was pre-pandemic, and it likely will never return to where it was in early 2020.

Deflation spiral

The decline in M2 will likely assist in causing inflation to fall over time. If the money stock continues to fall, however, it could lead to "outright deflation," where prices will start to generally decline and the rate of inflation will fall below 0% for the first time since the Great Recession, Economics Uncovered's Anastasiou said. Deflation, wherein inflation rates go negative and prices fall throughout the economy, can lead to diminished purchasing power and a rise in unemployment.

"There's a very good reason that declines in the M2 money supply are generally avoided," Anastasiou said. "For a fractional reserve, debt-driven economy, declines in M2 are akin to economic starvation."

Declines in M2, as the US is seeing now, have been correlated with economic depressions and panics, Anastasiou said.

However, during the Great Recession, from December 2007 to June 2009, the last time deflation occurred, M2 actually increased by roughly $1 trillion, rising from $7.472 trillion to $8.441 trillion, even as annual prices fell by 2%.

While many economists believe that the Fed is unlikely to reach its 2% inflation goal anytime soon, Luskin of Trend Macrolytics believes that the ongoing decline in M2 will have a significant impact on prices and, combined with the lagged effects of the Fed's rate hikes, trigger deflation as soon as January 2024.

"This is unknown territory," Luskin said.