Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

3 Nov, 2022

By Corey Paul

|

The November midterm elections will decide control of the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. |

Stalled efforts to reform the federal permitting process for energy infrastructure could resurface after the Nov. 8 U.S. midterm elections even if Democrats lose one or both chambers of Congress.

|

But the tight contest for control of the federal legislature also carries important implications for how and when the next crack at passing permitting legislation might take shape.

Nonpartisan public polling suggests close races for control of the evenly divided U.S. Senate as well as the House of Representatives, where Democrats have an eight-vote majority. If Republicans win the House, as election forecasters project, some Washington observers still see the possibility for a compromise measure.

"It's pretty close to a jump on permitting reform in the current political dynamic," Rob Rains, senior energy analyst with independent research firm Washington Analysis, said in an interview. "It is going to depend on the outcome of the election."

Lawmakers from both major parties released proposals for permitting bills that offered a sense of policy priorities and potential battle lines. U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., tried unsuccessfully to pair permitting policy updates with a continuing resolution to fund the government in September. Seventy-two House Democrats had opposed that approach.

Still, there was talk about the potential for compromise between Manchin's proposal and a more aggressive proposal by Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, R-W.Va., which most Senate Republicans favored.

Each package aimed to streamline permitting and speed up federal reviews for a range of energy projects, and both Manchin and Capito expressed a willingness to negotiate a new version of a reform bill.

The stakes for the energy sector are significant.

Electric transmission projects face serious permitting obstacles that come with building interstate infrastructure in the U.S., and Democratic lawmakers want to help site transmission projects in support of the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act, with its billions in energy and climate spending. Republicans, and some Democrats including Manchin, also want to streamline the permitting process for interstate gas pipeline companies and other infrastructure developers under the National Environmental Policy Act and the Clean Water Act, after a series of major legal setbacks for oil and gas projects upended billions of dollars in spending in recent years.

Window for compromise

If Democrats return to Washington, D.C., on Nov. 14 having lost both houses of Congress, they could feel greater pressure to pursue permitting reform in the lame duck session before the 118th Congress begins January 2023, according to Christi Tezak, managing director at ClearView Energy Partners. Potential vehicles could be an omnibus spending bill after the midterm elections or a defense authorization bill.

"If chambers turn over, then the Democrats would have the motivation to move something this session in order to say that's been done already, so we won't need the Republican Congress to do permitting reform," Tezak said. "You would get something milder. For exactly that reason, Republicans would want to find a way to stymie it so that they could do more and possibly attach it to something they feel that Biden would be able to veto."

Washington Analysis pegged "just-above-even odds that a deal may be struck to allow permitting reform to go forward."

"We recognize that the window is small and, depending upon the outcome of the elections, Republicans may have no desire to negotiate a compromise measure, instead opting to wait until after the 2024 presidential election, when the party may hold trifecta rule," Rains said in a recent note to clients.

'A possible future for permitting reform'

Manchin's proposal had sought to limit environmental permitting reviews to two years, shorten the timeline for public comments, and curb states' ability to hold up pipeline projects over water quality issues.

Capito's proposal called for writing into the law Trump-era reforms that sought to rein in state water quality reviews under the Clean Water Act that some states such as New York have used to oppose pipeline projects. The Republican permitting reform bill would have also codified a 2020 regulation that sought to limit the scope of environmental reviews and, like Manchin's proposal, established a two-year deadline for the reviews. The Biden administration moved to reverse the regulation in June.

Another provision in Capito's proposal would seek to give states more control over oil and gas leasing on certain federal land within their borders.

The separate permitting packages had also called for expediting approval of the long-delayed Mountain Valley Pipeline LLC natural gas transportation project, a priority for both West Virginia senators. The Mountain Valley provisions represented "a recognition that the biggest single issue is unending court reviews of these projects," according to James Coleman, an energy law professor at Southern Methodist University.

S&P Global Ratings also described litigation as the "most meaningful source of construction delays and cost increases" for the midstream sector. Ratings said that "any reforms that can be passed into law" would be unlikely to prevent litigation against projects. But Ratings nonetheless described Manchin's proposed permitting overhaul as a more "immediate and impactful driver of midstream credit quality" than the Inflation Reduction Act.

"It illuminates a possible future for permitting reform, one that limits the scope and time frame of environmental reviews of major energy projects such as pipelines, transmission lines, and wind farms," Ratings said.

Mountain Valley

One controversial provision for Republicans in Manchin's permitting reform push was a section meant to speed the siting of electric transmission. Some Republicans raised concerns that the bill would override state authorities by giving federal regulators power over transmission projects around the country.

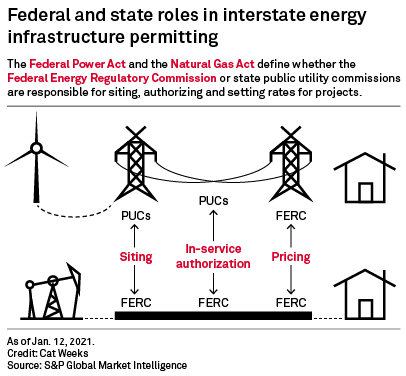

The federal government closely regulates the siting of gas transportation infrastructure under the Natural Gas Act. The government does not have the same authority over siting electricity infrastructure, which is mostly left to the states under the Federal Power Act, although large transmission lines often require some sort of federal permitting.

"Both the Capito bill and the Manchin bill seemed to be shuffling around authorities," Coleman said in an interview. "A real permitting reform bill that would actually get passed would have to be more thoroughgoing."

The recent drive for permitting changes nonetheless presented a promising sign for the long-term prospects of permitting reform because it showed that "it is not just industry or market-oriented voices saying we need to speed up permitting," Coleman said. Provisions of the permitting package had also been applauded by grid expansion advocates and some clean energy groups.

"If it is not addressed this Congress, it will certainly be a priority for the 118th Congress, regardless of who is in charge," Kellie Donnelly, former chief counsel for the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, said during an event at Columbia University's Center on Global Energy Policy days after Manchin's bill faltered.

"But this a big priority for the Republican caucus," Donnelly said.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.