Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

13 Oct, 2022

By Brian Scheid and Umer Khan

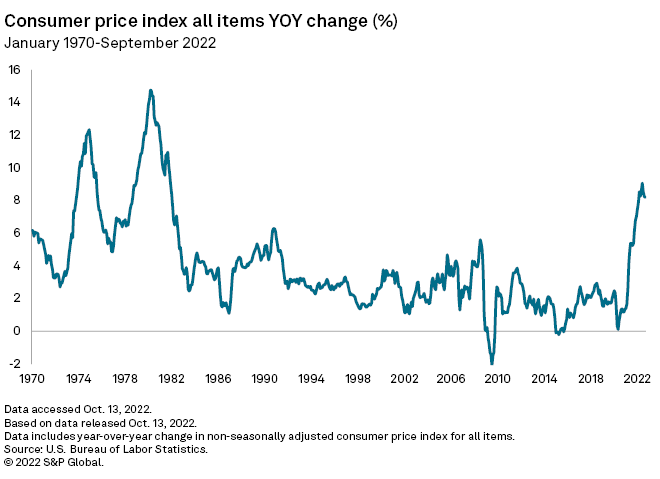

A key U.S. inflation measure surged in September to its highest level in more than 40 years, indicating that prices in the U.S. may not have peaked yet.

The core consumer price index, which excludes food and energy from the broader government measure of price changes, increased 6.6% from September 2021, the largest annual increase since August 1982, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported Oct. 13. Economists expected the figure to increase by 6.5%, according to Econoday.

The broader index, the market's preferred measure of inflation, jumped 8.2% from September 2021 to September 2022, just above economists' expectations of 8.1%, according to Econoday.

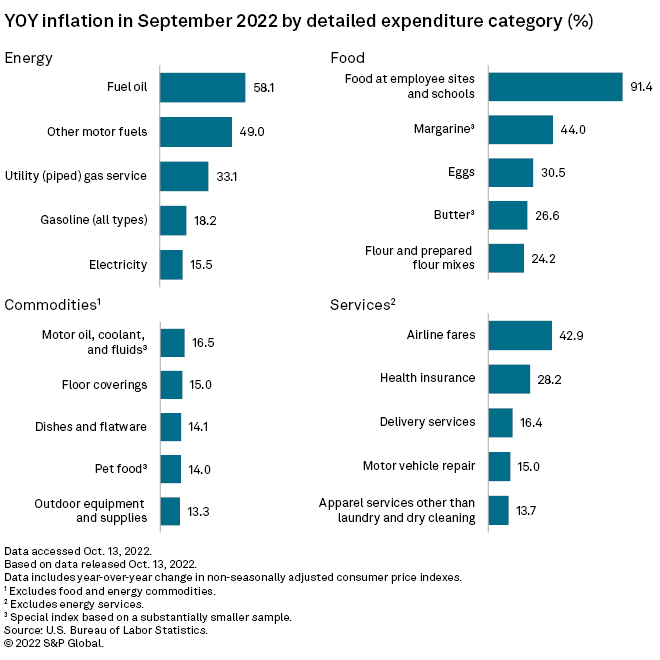

Energy prices continued to record large year-over-year increases, with fuel oil up more than 58% from September 2021. Services also saw big jumps, with airline fares, for example, rising nearly 43% and health insurance up over 28% from a year ago.

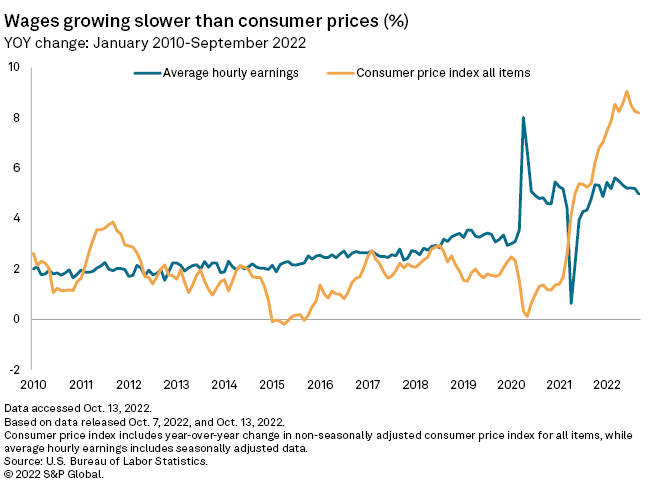

Average hourly earnings grew by 5% from September 2021 to September 2022, down from 5.2% in August and the slowest pace of yearly growth since December 2021.

While the unemployment rate remains relatively low, at just 3.5% in September, and U.S. businesses have more than 10 million job openings they are unable to fill, wage increases have begun to dip, remaining well below the pace of inflation.

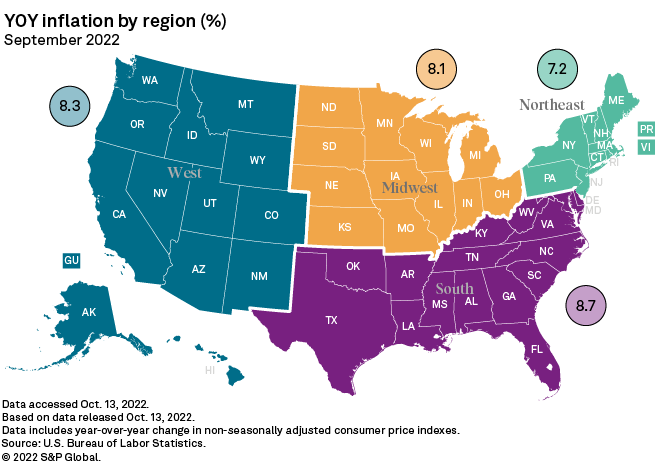

Inflation continues to impact regions differently. Year-over-year inflation grew by 7.2% in the Northeast, but 8.7% in the South.

Fed staying aggressive

The higher-than-anticipated increase in inflation threw more cold water on any hopes that the Federal Reserve's aggressive pace of rate hikes will slow anytime soon.

"Today's inflation data keeps pressure on the Fed to continue raising interest rates aggressively," said Ken Matheny, executive director for U.S. economics at S&P Global Market Intelligence. "Any Fed pivot is at least 18 months away."

The Fed has raised its benchmark federal funds rate by 300 basis points since March and increased rates by 75 bps at each of its past three Federal Open Market Committee meetings. After the release of the inflation data, the odds of another 75-bps hike at the Fed's November meeting were at about 99.8% as of 11:42 a.m. CT on Oct. 13, according to the CME FedWatch Tool, which measures investor sentiment in the fed funds futures market. The odds of a 100-bps increase were at about 0.2%.

"Any thoughts that U.S. inflation might be starting to settle down have been dashed," said Michael Hewson, chief market analyst with CMC Markets. "Any prospect of a pivot looks further away than ever."

With inflation remaining at historically high levels and the labor market staying persistently tight, the majority of the futures market now sees the Fed hiking rates another 175 bps over its next three meetings. This would bring the federal funds rate from its current range of 3% to 3.25% to 4.75% to 5% by February 2023, likely further increasing mortgage and other borrowing costs.

The rate has not been that high since 2007.

Future market expectations for the path for the fed futures rate may ultimately prove to be modest as inflation remains sticky in coming months, said Michael Crook, chief investment officer at Mill Creek Capital Advisors. Benchmark interest rates will climb above 5% before central bank officials consider easing from their policy push, Crook said.

The latest inflation data will likely continue to weigh on the sagging equity market, push bond yields higher, particularly shorter-dated yields, and accelerate the ongoing U.S. dollar rally.

The Treasury yield curve is likely to steeply invert — a recession signal where yields on short-term bonds rise higher than those for longer-dated debt — in the first quarter of 2023 as the Fed continues to raise rates, Crook said.

"At that point, we'll have spent down excess COVID savings and declining home prices will be weighing on households," Crook said. "It will be very difficult for consumers to keep up in real terms."