Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

6 May, 2021

By Brian Scheid

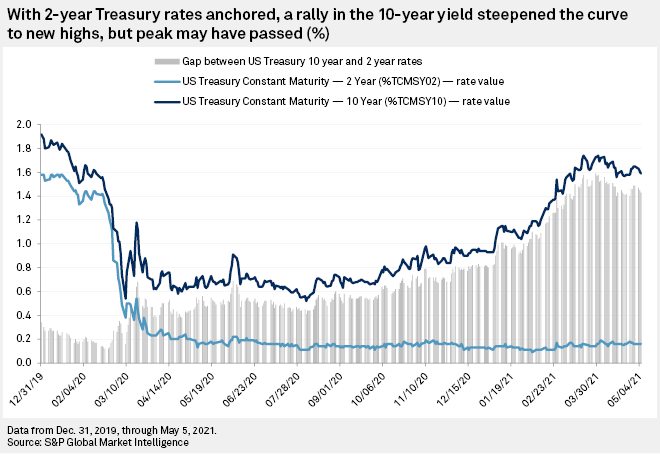

A stagnant U.S. government bond market in the face of a warming economy in recent days has fixed-income analysts wondering if the peak in yields has already come and gone.

Less than a month ago, analysts expected record supply and rapidly improving economic data to push the 10-year Treasury yield to 2% for the first time since July 2019. The benchmark 10-year yield serves as both a broad indicator of investor confidence and a proxy for mortgage rates.

But bond yields, which move inversely to bond prices, have instead slipped, with the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield settling at 1.59% on May 5 and trading as low as 1.56% on May 6, down 18 basis points from its March 19 peak.

"Nothing it seems can move U.S. Treasury yields much higher than they are now," said Antoine Bouvet, a senior rates strategist with ING, in an interview.

Investors continue to seek the relative safety of government bonds even as the domestic jobs picture improves and new highs are set in equity markets. As of the May 5 close, the S&P 500 was up about 11% on the year, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was up 11.8%, and the Nasdaq Composite Index was up 5.4%. All three indexes settled at new record highs in April.

But rather than waning as the domestic economy eases into a post-pandemic recovery, demand for the safety of bonds has persisted despite rallying equities, promising jobs data and other factors that analysts expected would drive up yields.

"Markets are not playing by the projected playbook," said Andrew Brenner, head of international fixed income at National Alliance Securities, in a May 6 note. "With employment rising and economic numbers soaring in many instances, treasuries are not going down."

Brenner said yields could get some lift from the Bureau of Labor Statistics jobs report on May 7 if it exceeds expectations. The agency last reported that 916,000 nonfarm payroll jobs were added in March, and expectations for the April jobs number have been as high as 2.1 million, Brenner said.

Another strong jobs number could put further pressure on the Federal Reserve to tighten its ultra-loose monetary policy, put in place in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has repeatedly said the central bank will not raise rates nor begin discussions of tapering bond purchases until its employment and inflation goals are met.

Bond yields have been kept down as the Fed has given no indication it is backing off its current course, including its monthly purchases of $80 billion worth of Treasury securities and $40 billion worth of mortgage-backed securities.

Bouvet with ING said yields may remain steady until the Fed indicates a shift in this policy.

"In reality, better job numbers and continued inflationary pressure are going to be hard to ignore by the Fed, so data still matter," Bouvet said. "This being said, they've stuck to the line so far, and it seems like some Treasury bears have thrown in the towel and will probably have another go in the summer."

The Fed's dovish policy has anchored the Treasury two-year bond yield at an average of 0.14% this year, down from 0.35% in 2020. And with the 10-year yield rising earlier this year, the yield curve, which can indicate an economy's path from recession, has steepened. The gap between the two- and 10-year yield was a high as 159 basis points on March 29. It closed at 143 basis points on May 5.

Despite the recent dip in the 10-year yield, the yield curve has more room to steepen, said Kathy Bostjancic, chief U.S. financial economist with Oxford Economics.

"We believe the faster GDP and inflation, moderate rise in inflation expectations and tapering of [bond purchases by the Fed] will lift 10-year yields higher," Bostjancic said in an interview.

Bostjancic forecasts that the 10-year Treasury yield will rise to 2% by the end of 2021 and to 2.45% by the end of 2022.