S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

20 Aug, 2021

By Camille Erickson

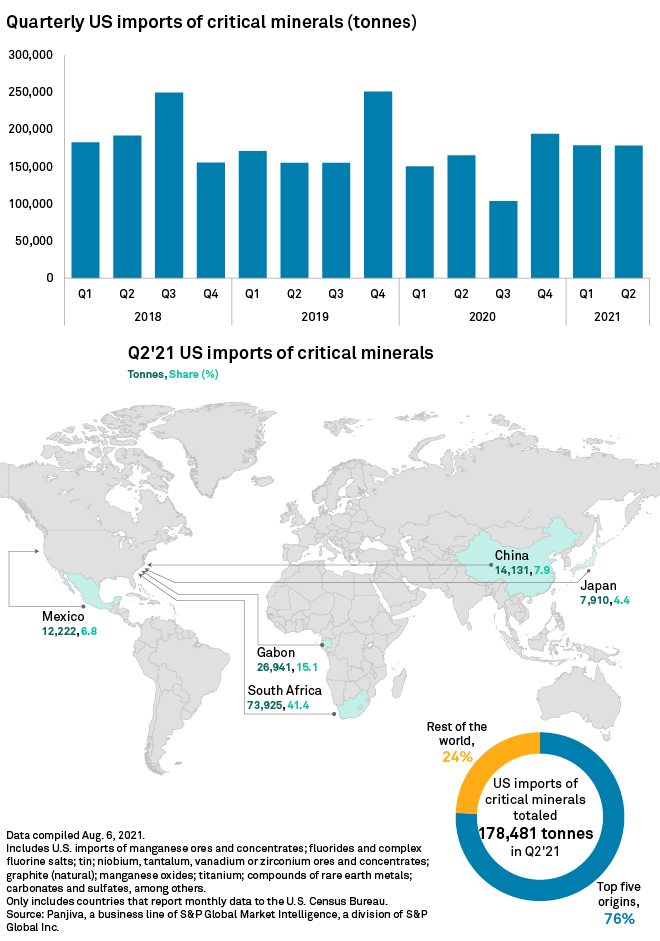

U.S. imports of critical minerals increased 7.9% in the second quarter on a year-over-year basis, while staying relatively flat quarter over quarter, according to an analysis by S&P Global Market Intelligence.

The volume of critical minerals flowing into the country in the first half of 2021 surpassed the 316,108 tonnes imported in the first six months of 2020 by 41,209 tonnes, according to the data.

Roughly three dozen materials fall under the U.S. Interior Department's list of critical minerals deemed to be important to national security and the economy. That includes the manganese and graphite used in electric vehicle batteries, the rare earth elements installed in the magnets used in wind turbines and EV motors, and several other materials required to build clean energy technology.

The majority of the critical minerals imported during the quarter came from South Africa, with 41.4%, and 7.9% were shipped from China, according to Market Intelligence data. Gabon, Mexico and Japan were also among the top sources of critical minerals for the U.S.

"We are dependent upon different countries, most notably China, for a number of our critical mineral resources," said Abigail Wulf, director of critical minerals strategy for Securing America's Future Energy, a group advocating for greater U.S. energy independence. "We are 100% import-reliant on 13 of the 35 critical minerals that the Department of Interior has classified."

The Biden administration has been working to boost the country's control of critical mineral supply chains and bring clean energy manufacturing to U.S. shores. The effort is an attempt at overcoming reliance on other nations not only for supplies but for infrastructure and processing capacity, according to industry experts.

China maintains a firm grip on the processing of several critical minerals. For instance, the country processes approximately 90% of the world's rare earth elements, along with 50% to 70% of lithium and cobalt, according to the International Energy Agency.

Furthermore, a lack of sufficient midstream infrastructure in the U.S. means critical minerals often must undergo various chemical processes — such as concentrating, refining and smelting — elsewhere. Battery anode, cathode and electrolyte production infrastructure is also lacking in the country.

However, Wulf lauded the recent infrastructure package passed in the Senate for dedicating $6 billion in funding to a new U.S. Energy Department loan and grant program aimed at advancing battery material processing, as well as battery manufacturing and recycling.

"We see that as being really critical to bringing back some of the crucial midstream components that we are very much lacking here in the U.S. and North America more broadly," Wulf said.

'We are stuck'

The Biden administration has made repeated calls to secure critical mineral supply chains. The administration wants to diversify the sourcing of the materials needed to "help combat the climate crisis," it said in early June.

"If we want to have more secure supply chains, that means thinking about having more or most of the supply chain in the U.S. or in allied countries," said Ian Lange, an economist at the Colorado School of Mines. Lange also was a White House economist under former President Donald Trump.

On June 8, the Biden administration released a 100-day review of supply chains and called for greater investment in "sustainable domestic and international production and processing of critical minerals," with a particular emphasis on pivoting away from "adversarial nations" such as China.

Current permitting regulations can also hinder the expeditious development of more mining and processing infrastructure, Lange explained.

Although the Biden administration has considered ways to potentially expedite offshore wind energy or transmission line permitting, "there hasn't been the same sort of discussion around mining or smelters," Lange said. "That's certainly one of the issues."

Focusing on just the critical mineral imports does not tell the entire story of what is happening to supply chains either. "It's important to recognize the difference between importing the actual mineral product itself and having that mineral product embedded in something else," Lange said.

Many critical minerals are imported into the U.S. after being installed in a product such as a solar panel or an EV battery. While U.S. imports of critical minerals have remained relatively unchanged in recent years, imports of batteries and solar panels have surged.

That makes the U.S. potentially vulnerable to supply disruptions and trade restrictions, Lange said.

"If somebody doesn't want to sell us that product, we are stuck in some sense," Lange said. "We don't have another way to get it. You could just import the mineral itself, but we also don't have many production facilities to take that and put that into a product, like solar panels or wind turbine motors."