Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

11 Mar, 2021

Proposals to form a national clean electricity standard have become a central focus of climate change legislation in the new Congress as U.S. President Joe Biden pushes for a carbon-free power sector.

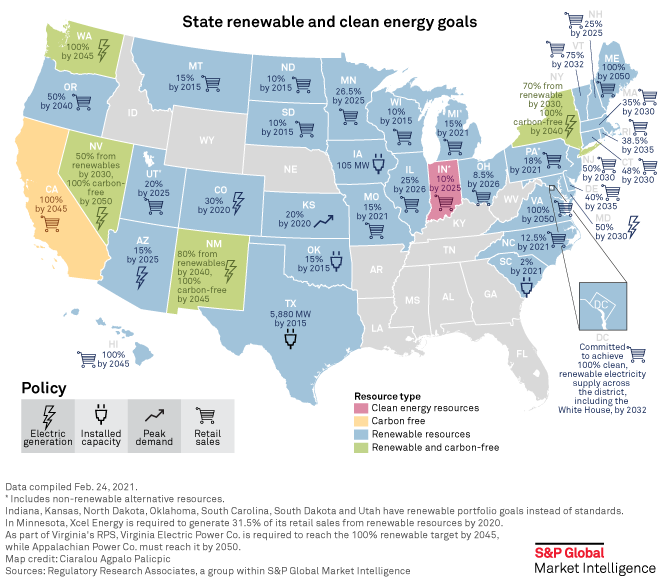

The concept has support from Democrats and Republicans, with nearly 40 U.S. states already adopting renewable or clean energy goals or standards, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. But lawmakers backing a clean electricity standard, or CES, still need to resolve differences over when the U.S. power sector would need to decarbonize, among other issues.

Those matters may need to be decided soon, with Democrats hoping to work on infrastructure legislation that could contain climate measures now that the lawmakers have completed work on another coronavirus relief bill.

A clean electricity standard "should be the center of an infrastructure plan that we look forward to working on after we get through the [COVID-19] recovery package," U.S. Sen. Tina Smith, D-Minn., who is preparing to reintroduce CES legislation, said during a recent event on pathways for enacting a CES.

Biden is targeting a zero-emissions power sector by 2035, in part through the formation of a CES. In response to that goal, Democrats in the U.S. House Energy and Commerce Committee introduced a broad climate bill in early March that included a CES aiming for 100% carbon-free power by the same year. CES bills in Congress have generally made room for a wide range of qualifying technologies, from renewable energy to nuclear power and coal- and natural gas-fired plants equipped with carbon capture.

Although Democrats control both chambers of Congress, the party is not entirely unified on its climate and energy agenda.

U.S. Rep. Kurt Schrader, D-Ore., co-authored a bipartisan CES bill in late 2020 with Rep. David McKinley, R-W.Va. The bill targets an 80% reduction in power-sector carbon dioxide emissions by 2050. In exchange for the mandate, the legislation would prohibit the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency from enforcing greenhouse gas performance standards for power plants under Title 1 of the Clean Air Act unless emissions rise by more than 6%, clean energy research programs authorized under the legislation are not fully funded or the clean energy standard is not being enforced.

Some utilities could decarbonize before 2050, but a nationwide goal of zero emissions by 2035 "is pretty unrealistic," Schrader said during a March 2 webinar hosted by the Bipartisan Policy Center. "We're willing to work with folks, but we want to be realistic."

Those intraparty divisions could also extend to the Senate, where Democrats hold a narrow majority. Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., who chairs the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, has defended the role of fossil fuels in power generation and criticized some of Biden's more aggressive clean energy actions during his early days as president.

Although Manchin has said he is open to a wide range of climate policies, he has made it clear that any legislation he supports cannot exclude fossil fuels.

"I think that we can do [the clean energy transition] and move forward, but we're not going to eliminate," Manchin said March 10 at a policy forum hosted by the American Council on Renewable Energy. "You can't just say we're going to eliminate using all fossil and coal's going to be out, oil's going to be out, everything else, gas is going to be out of it."

Democratic leaders, including Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., have said they could move a big infrastructure bill through the reconciliation process, which allows legislation to pass the Senate with support from a simple majority rather than the 60 votes needed to avoid a filibuster. But even if Congress considers CES legislation with later and more flexible targets, Smith acknowledged the obstacles to enacting such legislation, particularly in a narrowly divided Congress.

"We live in a hyper-partisan environment. I'm not naive about that," Smith said at a separate event hosted by the Carbon Capture Coalition. "But I think from a policy perspective, [my proposal] has the makings of a bipartisan bill."

| To view the map in a higher resolution, click here |

Negotiations

House Democrats' 2035 CES proposal came from the Energy and Commerce Committee, which will play a key role in shaping climate legislation from the lower chamber. But committee leaders may have to balance their bill against other CES proposals to broaden political support.

McKinley and Schrader said they are working to address Republican and Democratic concerns with their proposal in Congress. McKinley said he would like to see revisions to the EPA's performance standards for new and modified power plants to make upgrades easier while not upsetting environmental interests that want robust emissions standards for those facilities.

"We're negotiating how we can best find a new new-source standard that [overcomes] the objections or how we can get past some of the objections that could be out there," McKinley said.

Smith's bill could also offer a fresh chance at bipartisan agreement. She plans to reintroduce her CES legislation along with fellow Sen. Ben Ray Luján, D-N.M., who had co-sponsored a companion bill to Smith's proposal when he was a House member last Congress.

Previously, Smith proposed a clean electricity standard that would achieve zero net carbon emissions by 2050. She has not said whether she will move up that timeline but emphasized that her approach would give states and utilities flexibility in how they grow their percentage of clean energy generation.

That flexibility will be key, according to utilities. Xcel Energy Inc., which aims to decarbonize by 2050, supports legislation from Rep. Diana DeGette, D-Colo., that would establish a federal clean energy standard requiring utilities to achieve net-zero emissions by midcentury. The bill would award a credit for every carbon-free megawatt-hour of electricity utilities produce and for each ton of carbon removed from the atmosphere through carbon capture, utilization and storage.

But the bill would move up the net-zero deadline to 2037 if technologies to achieve that target are developed sooner. Whichever CES proposal goes the furthest, Xcel has said states, most of which already have renewable and clean energy goals, must play a key role in fulfilling the policy's requirements.

"It's really got to keep states in the driver's seat on resource planning," Xcel's director of energy and environmental policy, Jeff Lyng, said at the Bipartisan Policy Center event.