S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

22 Sep, 2022

Regulatory measures aimed at curtailing China's access to cutting-edge chips risk eating into profits for U.S. semiconductor companies, policy and tech experts warn.

The Commerce Department's Bureau of Industry and Security, or BIS, implemented new restrictions in August that limit the ability of U.S. companies to export technologies used in the design and manufacturing of advanced semiconductors without prior approval from the department. The restrictions cover two specific types of semiconductors often used for military purposes, as well as the specialized software used to make transistors 3 nanometers or smaller.

While the export rules apply broadly, China is expected to be among the countries facing the most practical impact due to concerns about U.S. technologies potentially being used in Chinese military equipment. The Biden administration is also expected to block U.S. companies from exporting chipmaking equipment to Chinese factories that produce advanced semiconductors.

Limiting access to Electronic Computer-Aided Design, or ECAD, chipmaking software in China could hamper the country's efforts to produce next-generation chips. But the export control measures may also have adverse effects on U.S. companies that rely on Chinese manufacturing facilities and sales.

"The U.S. government is trying to leave no stone unturned in terms of obstructing China's development of nascent emerging technological advancements that may or may not end up being fruitful," said Sarah Kreps, a nonresident senior fellow and expert in foreign policy and emerging technology at The Brookings Institution and director of the Tech Policy Institute at Cornell University.

Unintended consequences

Cadence Design Systems Inc., the world's leading ECAD software provider, Advanced Micro Devices Inc., Applied Materials Inc., Synopsys Inc. and NVIDIA Corp., among others, all stand to be impacted by the export ban.

"[The export controls] are fairly big for both AMD and Nvidia," said Byron McKinney, product management director for trade finance and compliance solutions at S&P Global Market Intelligence. "China was a big market for them, and there's a lot of manufacturing in China around the kind of civilian purposing of those chips into various consumer goods."

AMD executives downplayed the risk, saying at a Sept. 15 investor conference that the export controls would have a "minimal" impact on its business.

Nvidia in an Aug. 26 regulatory filing said about $400 million in sales to China

AMD did not include a geographic breakdown of its revenue in its latest quarterly results.

The impact of the export control rules could be especially substantial if the Biden administration takes additional steps to codify existing restrictions and enact broader regulations to restrict the sale of advanced chipmaking equipment and select artificial intelligence computing chips to China.

"While we are not in a position to outline specific policy changes at this time, we are taking a comprehensive approach to implement additional actions necessary related to technologies, end-uses, and end-users to protect U.S. national security and foreign policy interests," a Commerce Department spokesperson said. "This includes preventing China's acquisition and use of U.S. technology in the context of its military-civil fusion program to fuel its military modernization efforts, conduct human rights abuses, and enable other malign activities."

U.S. semiconductor manufacturers can apply for licenses from the Commerce Department to skirt the restrictions and export certain technologies to China. An August report by The Wall Street Journal found that 88% of such applications were approved in 2021, compared to 94% in 2020.

"These barriers are kind of pseudo barriers, and it's adding paperwork for these companies," Kreps said. "In almost all cases, they're approved."

Nvidia said in an Aug. 31 SEC filing that the U.S. government would allow the company to continue its development of H100 integrated circuits in China, though sales of the chip are still banned in China and Russia. An Nvidia spokesperson declined to comment in an email to S&P Global Market Intelligence. Spokespersons for AMD, Applied Materials and Cadence did not respond to requests for comment.

Synopsys has been working with industry groups and engaging with government representatives since February to examine the Wassenaar Arrangement, an export control regime comprised of 42 countries whose members exchange information on transfers of dual-use goods and technologies. The company will participate in the upcoming BIS public comment period, a company spokesperson said.

Working as designed

Chris Miller, a Jeane Kirkpatrick Visiting Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, said the high acceptance rate for licenses from the Commerce Department should be considered in context.

"It means that policy is clear and has been tightening over the past couple of years," Miller said.

BIS will likely implement new licensing requirements for specific software tools and machinery used in chipmaking, as well as for different types of chips in the near future, Miller added.

Policy and tech experts said the export control measures intended to temper China's chipmaking capability are likely to succeed.

"China really would struggle to find any alternatives to [the technologies] and would probably end up using less efficient and lower-grade chips and technologies," McKinney said. That could impact both the civilian and military technology in the country, McKinney noted.

The loss of ECAD software is a particular blow to the Chinese semiconductor industry.

"To actually design those chips is really difficult," said Edward Anderson, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin's McCombs School of Business. "You have to automate the design because no human being can design the billions of circuits that go on an individual semiconductor."

Chipping away at market share

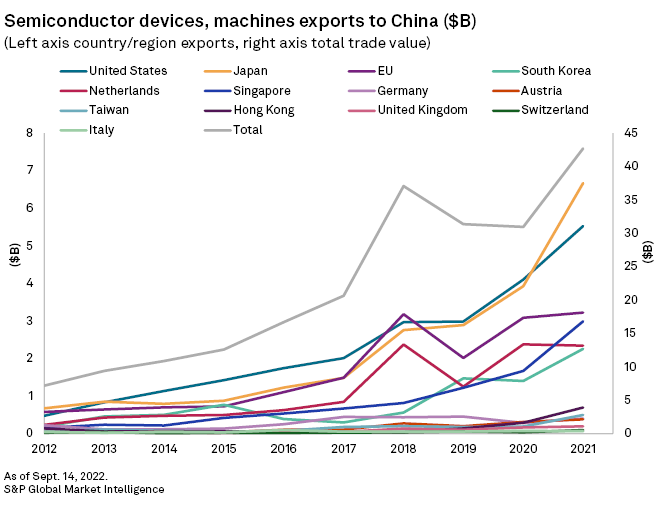

While Taiwan produces more than 90% of advanced semiconductors, the U.S. is second only to Japan in terms of the value of semiconductor-making machines it exports annually to China, which is why the Biden administration's efforts to curb China's access to this technology is significant, analysts said.

Even incentives for ramping up domestic production now reflect the increasingly global nature of the semiconductor supply chain, Kreps noted.

In the U.S., the CHIPS and Science Act, signed into law Aug. 9, includes incentives for foreign companies like Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. Ltd., which provide most of the chips used in the U.S. for commercial and military applications. The two companies have invested billions in building plants in Texas and Arizona, respectively.

"Samsung sort of paused and said, 'These [facilities] are becoming a lot more expensive than we anticipated. And why should we not benefit from these incentives?'" Brookings' Kreps said. "If they would have otherwise employed their own workers in Taiwan or South Korea, why shouldn't they benefit from that?"

In response, South Korea, where Samsung is headquartered, passed its own subsidy package for the semiconductor industry.

"Do we end up in this tit-for-tat protectionism race to the bottom where everyone does what they think is sensible at the individual level?" Kreps asked.

The CHIPS Act may not solve all of the industry's problems, but it is consequential enough that it will result in market share growth for U.S.-based companies as supply chain capacity comes online, said UT-Austin's Anderson.

The industry still has work to do to reduce the cost gap between manufacturing in the U.S. and manufacturing abroad, said AEI's Miller. That could be aided by a tax credit provision included in the CHIPS Act for investment in semiconductor production facilities, Miller said. The provision creates a 25% tax credit for investments toward the manufacturing of semiconductors or of the specialized tools required in the semiconductor manufacturing process. The credit is applicable to production facilities available for use after Dec. 31, 2022, and for which construction starts before 2027.

"Manufacturing abroad is often cheaper because their government subsidies are larger," Miller said. "That ought to be addressed either by pressuring other countries to reduce the subsidization of their chip industries or by taking our own steps in the tax code, if necessary."