Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

14 Mar, 2022

By Karin Rives

Rising energy costs and political uncertainty in Europe sent carbon allowance prices on a roller coaster over the last three weeks, but the turbulence has not yet affected U.S. carbon credit prices.

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative's quarterly auction of allowances held March 9 resulted in the highest clearing price the 24-year-old program has registered: $13.50 for a ton of carbon dioxide. The auction brought in nearly $294 million for the 11 states participating in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern cap-and-trade market, the RGGI announced March 11.

The RGGI auction followed another record result set by the Western Climate Initiative's quarterly auction in February, where allowances cleared at $29.15. The California-Quebec-Nova Scotia cap-and-trade program has been operating since 2011.

Investors are flocking to the carbon credits in anticipation of more stringent federal and state climate policies that could increase demand for allowances. A review of the RGGI market to help increase the credit price, which was finished in 2017, also boosted investor interest, observers said.

The strong U.S. markets stand in contrast to the EU market's turmoil. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February and the subsequent energy crunch sent the EU carbon price tumbling from near record-highs of 95 euros per tonne on Feb. 24 to 58 euros on March 7. Prices have since recovered to levels seen in late fall.

Proceeds from carbon credit auctions are used for energy-efficiency programs, public transit and other initiatives to decrease greenhouse gas emissions. A significant portion of the EU revenue is also earmarked for energy infrastructure upgrades in developing member states.

Ukraine invasion's market impact

Because of the regional and national implications of carbon markets, climate change economists on both sides of the Atlantic are now closely watching prices that, for years, barely moved.

"Wars generate huge uncertainties, in particular when they involve energy," Valentina Bosetti, a climate change economics professor at Bocconi University in Italy, wrote in an email.

Before the invasion upended the energy landscape in Europe, carbon prices began to rise in 2021 and spiked after the Glasgow, Scotland, climate summit in November 2021.

Prices soared on investor expectations that fewer allowances will be made available as the continent's climate policies become more stringent in coming years, Bosetti said. High natural gas prices also pushed up allowance prices as European utilities used more coal and thus had to purchase more carbon allowances, Bosetti added.

The European cap-and-trade market is expected to generate more than 1 trillion euros over the next decade, more than the EU's entire pandemic recovery budget, according to Sandbag, a climate policy think tank in Brussels. The market is the cornerstone of the continent's ambitious climate plan.

A sensitive topic

Power plants and other polluters covered by cap-and-trade programs buy an allowance for each short or metric ton of carbon they emit, a mechanism created to incentivize investments in cleaner energy sources.

But when utilities pay more for releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, the cost may be reflected in higher consumer bills. Conversely, U.S. states or EU nations participating in carbon markets receive less revenue when prices dip.

"Price sensitivity is something we're going to have to be aware of," Joseph Majkut, director of the Center for Strategic and International Studies' energy security and climate change program, said during a March 10 webinar hosted by Resources for the Future.

"The political messaging can easily write itself, so analysts need to think carefully about ... the outcomes for consumers and firms in a carbon pricing environment on top of current conditions," Majkut added.

But Majkut noted that policymakers can cap high carbon prices and use market proceeds for consumer rebates to offset higher energy costs. "We don't have similar tools for volatile energy prices."

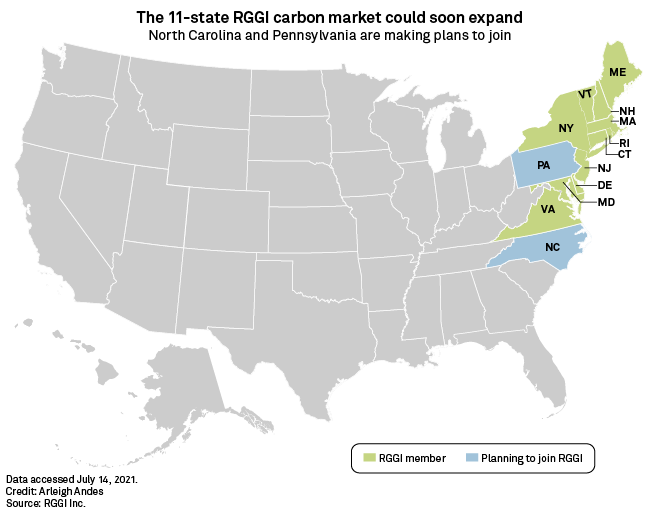

Carbon pricing cost and benefit concerns are on display in Virginia, where a newly elected Republican governor has pledged to remove the state from the RGGI, and in Pennsylvania, where Republican state lawmakers are trying to stop the state from entering the program in 2022.

While RGGI opponents decry any added costs, RGGI supporters note that the program works as intended by reducing emissions while raising revenue that helps states further mitigate and adapt to climate change. And that money can be substantial: Virginia received $230 million in allowance proceeds in 2021, its first year with the program.

The RGGI carbon market has been credited with helping New England and mid-Atlantic states reduce emissions faster than the country as a whole and was once viewed as a model for a nationwide program.

Carbon dioxide pollution from power plants in RGGI states dropped 47% between 2008 and 2017, according to an often-cited study by the nonprofit Acadia Center, a proponent of carbon markets. So far, RGGI allowance auctions have raised just under $5 billion in proceeds for the states.

Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont and Virginia participate in the RGGI market.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.