Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

5 Jan, 2021

By Saqib Shah and Gaurang Dholakia

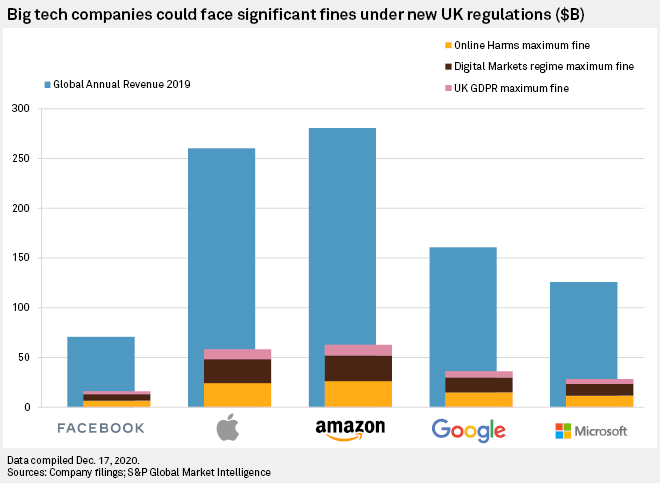

The coming year could be a challenging one for large tech companies operating in the U.K., as a raft of regulation aimed at the sector is set to take effect.

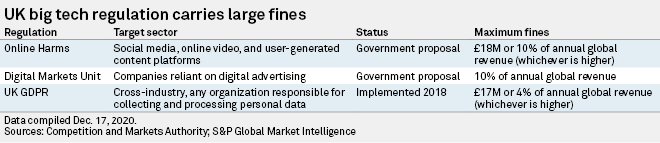

As they adjust to post-Brexit rules on data protection, firms also face a new U.K. competition regime aimed at digital markets, and local content moderation laws.

The U.K.'s proposals place the onus on social networks to remove harmful content, and seek to level the playing field between big tech and smaller would-be rivals through data-sharing and increased scrutiny of mergers and acquisitions.

Competition

The U.K. government said it would consult in early 2021 on legislation that allows for the creation of a dedicated supervisor for big tech, known as the Digital Markets Unit. Working within the mergers regulator, the DMU will apply a code of conduct to companies with a "strategic market status."

The new rules are expected to apply to Facebook Inc., Alphabet Inc.-owned Google LLC and a "handful" of additional firms, according to Lesley Hannah, a partner at law firm Hausfeld, who focuses on competition litigation and consulted on the digital markets proposal.

Provisions will seek to fill gaps in the current regulatory framework, specifically in the sharing and exchange of data between dominant services and their smaller rivals across the social media, e-commerce, and search sub-sectors, Hannah said.

Theoretically, the code could see Amazon.com Inc. required to share its trove of information on the purchasing habits of online shoppers with a new market entrant that would otherwise struggle to cater or advertise to potential customers, Hannah explained.

In Facebook's case, it could be asked to share data on which posts users interact with on their timelines. Google, meanwhile, could be forced to offer its search history data to alternative search engines. Its smaller rivals would then know how common it is for people to search for a popular term or query such as "COVID-19" for example, Hannah said.

"Google, Amazon, and Facebook have more than a decade's worth of the public's purchasing, social and search data," Hannah said. "If that info is made available to others, the rationale is that it would improve competition."

The new rules would also make it mandatory for mergers and acquisitions to be notified to the U.K.'s Competition and Markets Authority, or CMA.

The U.K. proposals suggest the country is aiming to introduce a "hybrid" version of the EU's Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act, establishing a "more stringent regime," Anthony Rosen, a legal director who advises clients in the digital and communications sector for law firm Bird & Bird, said. The DMU will not be able to break apart big tech as those powers have long been available to the CMA under the market investigation powers pursuant to the Enterprise Act, he added.

Content moderation

The U.K. is expected to make swift progress in 2021 on its draft law targeting material considered harmful on social media after criticism in Parliament over its delay.

The Online Harms bill – first announced in 2018 – is going to be a "big priority" for the government as it has bipartisan support and sits well with the public due to its focus on the wellbeing of younger internet users, Jo Joyce, senior associate, commercial tech and data, at law firm Taylor Wessing, said.

The proposal would impose a statutory duty of care on services that host user-generated content, ranging from Facebook to YouTube and gaming services, to remove unlawful material and implement measures for the reporting and removal of content that is harmful, but not necessarily illegal. Communications regulator Ofcom has been tasked with enforcing the law.

The regulation will not cost much to implement and can be portrayed as a "revenue raising tool," though the chances of large fines being levied are unlikely, Joyce said, pointing to the "reluctance" of GDPR regulators to hand down major penalties for data breaches amid the pandemic.

U.K. data regulator the Information Commissioner's Office in October reduced its GDPR fines for British Airways and Marriott by almost 90% and 81%, respectively, to £20 million and £18.4 million. The decisions were due to the impact of COVID-19 and the steps taken by the companies to mitigate the impact of the data breaches. The fines remain the largest for GDPR violations in the U.K. to date.

Despite eagerness to push the Online Harms bill through next year, it will be "hotly contested" every step of the way, according to Joyce. "As soon as it is introduced it will see legal challenges around its risks to freedom of expression," she said.

The government has already backtracked on some aspects of internet regulation, ditching plans to introduce age checks for adult sites and recently admitting that a provision in the Online Harms bill to include criminal sanctions for senior management would require secondary legislation.

Officials may have an easier time pushing the measures through if they better define what constitutes an online harm, Joyce said. They will likely work on broadening the scope of what is considered damaging to include misinformation and disinformation, in order to circumvent resistance around freedom of speech, she noted.

Data privacy

With the above changes to prepare for, tech firms in the U.K. likely breathed a sigh of relief that the country managed to agree a trade deal with the EU days before it exited the bloc on Dec. 31.

The deal gives companies extra time to ensure they comply with post-Brexit data protection law.

The U.K., along with other EU member states, incorporated the bloc's data privacy regulation, the GDPR, in 2018. Experts do not expect U.K. lawmakers to diverge from the GDPR in the coming year, but the way the rules are interpreted by the local regulator and courts could differ from their EU counterparts in the future, they said.

"The government has shown no inclination of departing from the GDPR," Joyce said. "There is no incentive in pursuing anything that makes it harder for companies to do business," she added.

Looking ahead, the two distinct regimes could result in different decisions from the U.K. and in the rest of Europe for cases that impact both territories, Seaton Gordon, a legal director within law firm Clyde & Co.'s London cyber team, said. As the U.K. no longer falls within the Court of Justice of the European Union's jurisdiction, the court would no longer be able to ensure consistency in decision-making, he added.

In practice, that means if there is a potential data breach involving the U.K. and France, "you could have two sets of investigations taking place, because you have two sets of regimes, two sets of data privacy regulators looking at the same facts, albeit through a national lens, and therefore you could get two different results," Gordon explained.