S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

26 Oct, 2022

By Ben Dyson

|

Gilt yields have been volatile in recent weeks as investors |

The U.K. pensions insurance market is expecting a surge in deal activity in 2023 after sharp rises in U.K. government bond yields greatly improved pension schemes' funding positions. That in turn has increased their ability to transfer their defined benefit pensions liabilities to insurers.

"We're expecting next year to be extremely busy. It could be the busiest year on record," Charlie Finch, a partner at consultancy Lane Clark & Peacock LLP, or LCP, said in an interview.

Defined benefit pension schemes pay pensioners a set amount for the remainder of their lives, and so place a heavy financial burden on companies that still have them. Many companies opt to buy so-called bulk annuities from life insurers to cover all or part of their obligations to pensioners. Bulk annuities either pay the scheme, known as a buy-in, or the pensioners directly, known as a buy-out. Drug company Sanofi, for example, insured £760 million of its U.K. pension scheme liabilities with Legal & General Group PLC in a buy-in transaction in October 2021.

The market could bring in £30 billion "or a bit more" in 2022, Finch said. While precise 2023 volumes are unclear, "I think we could see it being 50% bigger next year." The previous record was 2019's £43.8 billion, according to LCP.

Speed boost

Covering defined benefit schemes has been big business for the U.K.'s large life insurers in recent years. According to LCP, buy-ins and buy-outs totaled £27.7 billion in 2021. Aviva PLC led the market in 2021, transacting £6.2 billion of that business, according to LCP data. Standard Life Assurance Ltd. and Legal & General Group ranked second and third that year with £5.5 billion and £5.3 billion, respectively.

A pension scheme's ability to afford the premium for a bulk annuity depends on its funding position — how adequately its assets cover its liabilities. The calculation of the funding position is influenced by government bond yields, and recent yield rises mean that many schemes are now much better funded. "We've got schemes that have been able to bring forward their journey plans by four or five years relative to what they were expecting in terms of buy-out affordability, which is obviously great news for those pension schemes," Shelly Beard, U.K. head of pensions transactions at Willis Towers Watson PLC, said in an interview.

At the same time, the prices pension funds pay for buy-ins and buy-outs are falling because of widening credit spreads, stiff competition between insurers and lower costs for reinsurance purchased by insurers to lay off some of the longevity risk they assume when taking on pension scheme liabilities. LCP has revised its pricing estimates down twice in 2022 in response to lower-than-expected pricing.

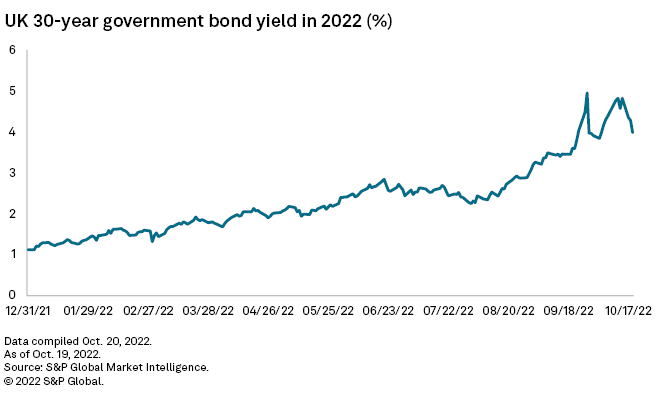

Yields on 30-year U.K. government bonds were volatile in late September and October following a package of tax cuts announced by the U.K. government Sept. 23. A Bank of England bond-buying program launched Sept. 28 sought to calm the markets, and yields have since fallen from a peak of 4.95% on Sept. 27 to 3.76% on Oct. 26, the day Rishi Sunak was declared the U.K.'s next prime minister. But they are still far higher than 1.12% at the start of the year and better than the 2.27% level at the beginning of August.

Most of the schemes whose paths to buy-out have been accelerated already achieved most of the improvement in funding levels before the latter half of September, Beard said, and so the yield spikes were "the icing on the cake," and more recent falls "won't have materially affected those pension schemes."

Short-term pain

The surges in yields have not been all good news for the schemes or their insurers. The yield spikes caused a short-term liquidity crisis for U.K. pension funds that used liability-driven investment, or LDI, strategies. The rises triggered collateral calls on the interest rate hedging derivatives the schemes held to protect themselves against falling interest rates. Pension schemes' liquidity buffers were smaller than those of insurers that used similar hedging strategies, and so, unlike insurers, they had to sell bonds to meet the calls.

Some schemes no longer had the liquidity in their investment portfolios to execute the buy-ins they were planning because of recent yield movements.

Because schemes are in a position to consider insurance sooner than they expected, they are struggling to sell the illiquid assets, such as real estate and infrastructure, on their portfolios in preparation for buy-in or buy-out. "It's been very challenging to sell illiquid assets on the secondary market and the haircuts that you have to take if you do want to get out of those illiquid assets are much higher than we previously experienced," Beard said.

The increase in the number of schemes being ready for buy-in and buy-out is putting a strain on insurers' resources. The main limiting factor in the short term is the number of people able to work on deals at insurers, brokers and pension administrators, according to Joanna Carter, a partner in risk settlement at consultancy XPS Pensions Group PLC. "There is a limited pool of experience across the market. Growing that experience takes time," Carter said in an interview.

The recent upheaval has also alerted companies to the risks contained in their defined benefit schemes. "This is just another reason to put in the money to move it to an insurance company," Finch said. "And if that money is less now than it was six months ago, then that's all the more reason to think about doing that."