S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

28 Jun, 2021

| Electric shovels on a road at the Escondida copper mine in Chile where lawmakers are debating new copper taxes. |

Latin America could be on the verge of a mining bonanza. Governments and businesses all over the world are rushing to cut their greenhouse gas emissions, and the region is a critical supplier of the minerals that underpin solar panels, wind turbines and electric vehicles.

But extracting those minerals is expensive and creates its own set of environmental and social consequences.

"People want to stop climate change," Juan Carlos Jobet, Chile's minister of energy and mining, said. "That requires copper. But they don't want more copper mining." Chile provides about one-fourth of the world's copper supply. Copper is used in electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels and electricity networks, such as transmission lines.

Under the Paris Agreement on climate change, nearly every country on earth pledged to limit global warming to "well below" 2 degrees C compared to preindustrial levels. To achieve that goal, the supply of minerals such as copper, lithium and zinc to the green-energy industry will need to grow fourfold in the coming decades, according to the International Energy Agency. Getting to net-zero emissions by 2050 would require six times more minerals.

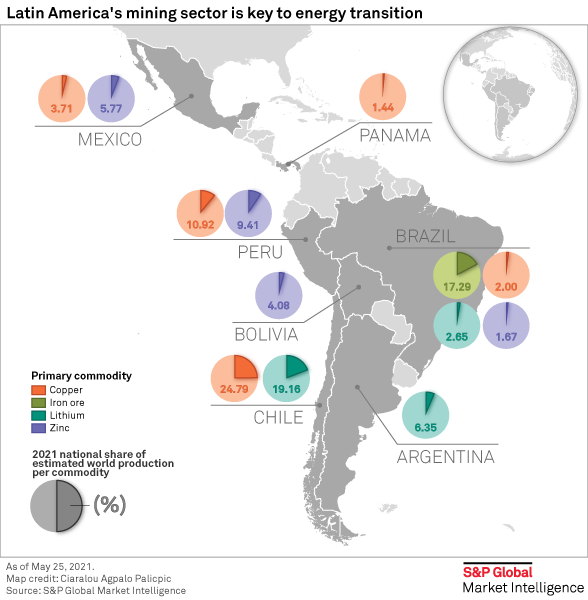

For Latin America, a big jump in minerals demand could fuel an economic boom: Mines in Chile, Peru and Mexico account for nearly 40% of estimated global copper production this year, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. More than 25% of the world's estimated lithium production is located in Chile and Argentina, while Peru, Mexico and Bolivia account for an estimated 19% of zinc production.

However, dramatically increasing production in Latin America faces serious challenges. Bureaucracy and a lack of local investment hindered exploration and development, according to Synergy Resource Capital, and the region's mining sector "remains underfinanced," Paola Rojas, a managing director at the firm, said. Recently, international mining companies have been spooked by growing social and political risks in major markets such as Chile and Peru, and there are questions about whether parts of Latin America are even open to new mining ventures.

Yet without more supplies from the region, the green-energy industry could find itself short of critical minerals.

|

|

"What we are seeing here [is] many groups [are] opposing more investment in mining because of its environmental impact, because of the impact it has on some local communities," Jobet said in May at a conference hosted by Columbia University. "Also, the political turmoil or the social unrest [is] hurting the long-term investments in mining."

Since 2019, Latin America has been roiled by demonstrations over what researchers call an "inequality crisis." When the coronavirus struck, a region already struggling with a slowing economy plunged into disaster, Mauricio Cárdenas, Colombia's former energy and finance minister and a visiting senior research scholar at Columbia University's Center on Global Energy Policy, said. Gross domestic product in Latin America and the Caribbean fell by an estimated 7.7% in 2020, the largest contraction in 120 years, according to the United Nations, as unemployment jumped to 10.7% and the poverty rate climbed to "unprecedented" levels.

Meanwhile, some governments in Latin America are looking to grab a larger share of mining profits, unsettling producers as local opposition to the industry grows.

In Chile, a debate over copper taxes has gripped the mining sector. "The whole industry is following the situation very closely," Kathleen Quirk, CFO of Freeport McMoRan Inc., which is considering expanding the El Abra copper mine high in Chile's northern desert, said at an investor conference in May. "The project ... could be a $5 billion, $6 billion project. And so making that investment requires that we understand what the rules are."

If Freeport-McMoRan decides to move forward with the El Abra expansion, executives say the development would take at least six to eight years, due in part to permitting requirements.

"It seems like, in some cases, permitting is nearly impossible" in Chile's mining sector, Christopher LaFemina, a senior equity research analyst at Jefferies LLC, said on a Freeport-McMoRan earnings call in April.

Those challenges underscore a wider risk that shortages of critical raw materials could stymie worldwide efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In May, the IEA said existing supply and investment plans for many critical minerals "fall well short of what is needed to support an accelerated deployment" of clean-energy technology. Any shortfall, the agency warned, could delay the transition to a zero-carbon economy in order to limit the effects of catastrophic climate change.

On June 8, the Biden administration outlined its plan to bolster domestic battery manufacturing and critical-mineral supplies. "America is in a race against economic competitors like China to own the [electric-vehicle] market — and the supply chains for critical materials like lithium and cobalt will determine whether we win or lose," U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said earlier this year. "If we want to achieve a 100% carbon-free economy by 2050, we have to create our own supply of these materials, including alternatives, here at home in America."

A recent run-up in metals prices offers a glimpse of the problems that future bottlenecks could cause. Renewable energy executives and analysts warned of potential disruptions to project development schedules as prices for iron ore and copper hit record highs, causing stocks of wind and solar companies to slump even as the world moves more aggressively to limit climate change.

| A solar photovoltaic plant developed by Total and SunPower in Chile's Atacama Desert. Copper is an essential input for solar panels. Source: TotalEnergies |

Tax questions

Mining companies are expected to increase spending on exploration in Latin America by about 20% in 2021 after investment fell by 21% last year amid COVID-related lockdowns, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. However, looking beyond the rebound analysts foresee in the next year or two, the long-term trend is concerning, said Kevin Murphy, a principal research analyst at Market Intelligence.

"Financing multibillion-dollar mines isn't how you necessarily build [shareholder] value," Murphy said, and "getting approvals these days for massive new developments is very difficult." As a result, Murphy said the industry is "focusing less and less on early-stage assets" in favor of adding production at or near existing mines, a cheaper and less onerous alternative. But some policymakers worry that the lack of grassroots exploration could hurt future production.

Increased investment is critical as existing mines approach peak output due to declining ore quality and dwindling reserves, the IEA said. Extracting metal from low-grade ore creates more waste and requires more energy, which increases costs and environmental damage. More than 80% of Chile’s copper, for instance, is produced in water-stressed areas. Water usage is also a flashpoint in the lithium industry, which is estimated to use nearly 2 million liters of water to produce one ton of lithium, according to the United Nations. In 2020, approximately 82,000 tons of lithium were produced outside of the U.S., which withheld production data.

"Projects today around the world, geologically, are more difficult," Freeport-McMoRan Chairman and CEO Richard Adkerson told analysts in January. The company's Cerro Verde copper mine in the desert highlands of southern Peru, for example, is a "big, low-grade" project requiring "huge investments in infrastructure and equipment and mill processing," Adkerson said. "And then you have these barriers to production that keep some attractive projects around the world from going forward."

The political winds in Latin America are particularly concerning for miners, Brian Menell, CEO of mining investor TechMet, said. "You have a serious risk in Chile and in certain other countries like Peru ... of a kind of populist-socialist backlash against the growing disparities and inequalities and aftermath of the present pandemic," Menell said. "It's not impossible you get nationalization of massive lithium resources."

Peruvian voters rattled the mining industry June 6 when they elected as president Pedro Castillo, a socialist who proposed new royalties on mineral sales and suggested renegotiating existing tax deals. In Chile, the government is trying to pare back a proposed copper tax after analysts warned it would stifle production.

"We have to see how Chile plays out, obviously, but we're still hopeful that that's going to proceed down the path where people understand the importance of maintaining stability and the importance of being able to attract capital,” Mike Henry, CEO of BHP Group, the majority owner of the Escondida copper mine in Chile's Atacama Desert, said in May at an investor conference. "Because, of course, Chile has fantastic copper resources, but for the big, ongoing investment into the country, the fiscal settings have to be attractive."

Freeport-McMoRan CFO Quirk echoed Henry. When asked about recent developments in Chile and Peru, Quirk told investors June 10 that "the industry is unlikely to take on substantial investments currently until there's more clarity around the fiscal regime there."

| Technicians completing construction of a new wind turbine in Israel's Golan Heights. An onshore wind farm requires nine times more minerals than a natural gas plant, according to the International Energy Agency. |

The 'contradiction'

Adding to the uncertainty is the increasing focus on environmental, social and governance issues among investors and corporate executives. Paradoxically, the technologies the world needs to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions are a product of mining, a notoriously dirty business that is often conducted in high-risk areas.

To date, that dynamic has played to the advantage of Chinese companies, which face less scrutiny on ESG issues than their western peers and have gone to "enormous lengths to increase ownership of and access to" critical minerals around the world, according to Wood Mackenzie, an energy research and consulting firm.

In its June 8 report, the Biden administration recommended that the U.S. government work with the private sector and nongovernmental organizations to "encourage the development and adoption of comprehensive sustainability standards for essential minerals," such as lithium and copper. The report noted that China processes 39% of the world's copper and "a large majority" of its lithium.

International mining companies said they share the Biden administration's ESG goals. "Growing demand must be met more sustainably," Henry of BHP told investors in May. "Better alignment will enable the transition to be achieved more sustainably, quickly and cost-effectively. Conversely, a lack of alignment will result in poor sustainability outcomes and slower and more costly progress on the energy transition."

|

|

Mauricio León, officer of economic affairs in the natural resources division of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, said existing legal and regulatory frameworks should be reviewed "to correct flaws or vices that discourage sustainable investment."

"Fiscal regimes should also be reviewed to improve revenue collection through instruments that make the system more progressive, equitable, and efficient and through capacities and mechanisms to minimize evasion and illicit flows," León said in an emailed statement. "The contribution of the mining sector to the mobilization of domestic resources needs to be strengthened in the short term for the post-COVID-19 recovery but without losing the long-term vision and delaying the required efforts to make the sector more sustainable to support ... the development of mineral-producing countries."

As countries in Latin America vie to attract investment, some worry there could be a race to the bottom on ESG standards, Rebecca Ray, a senior academic researcher at Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center, said.

"These countries have market share that is sufficient to be able to set standards and enforce them and not lose investment to other countries," Ray told the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, which monitors relations between the two countries, during a May hearing on China's activities in Latin America. "But they don't have the institutional support and capacity to carry it out in reality, which means our investors may be out-competed in these areas because of our standards."

With billions of dollars already invested in infrastructure, Latin America will remain an important minerals supplier as producers continue to operate existing mines and add incremental capacity where possible, Market Intelligence analyst Murphy said. But "the real question is going to be those potential massive new developments," the analyst said. "Will those be at risk?"