Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

16 Apr, 2021

By Brian Scheid

The Federal Reserve's grand experiment to let inflation run above 2% has begun to play out in government bond markets and the yield response so far seems to be defying expectations.

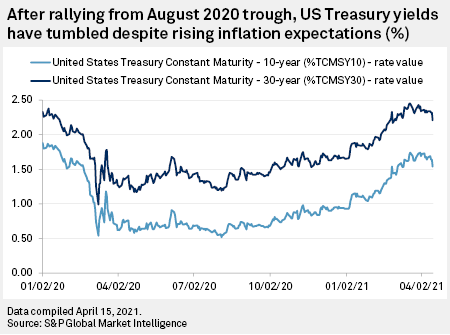

The Labor Department reported on April 13 that its consumer price index, a key measure of U.S. inflation, climbed 0.6% from February to March and 2.6% in the year since March 2020. Meanwhile, the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield dropped to 1.56% on April 15, from 1.73% on April 5.

That movement — contrary to analyst expectations that bond yields would rise as inflation does — has raised questions over whether bond investors were overlooking inflation risk and whether they had overpriced it into the market weeks earlier.

And with Fed officials offering few clues on just how long and just how high they will allow inflation to rise before they hike rates or announce another shift in the Fed's pandemic monetary policy, bond yields have become unmoored from predictions.

"The next few months could be very interesting on the inflation front … especially how the market reacts to it," said James Rossiter, head of global macro strategy at TD Securities, in an interview.

March's CPI gain was the largest yearly jump since April 2018 and slightly above most analysts' expectations.

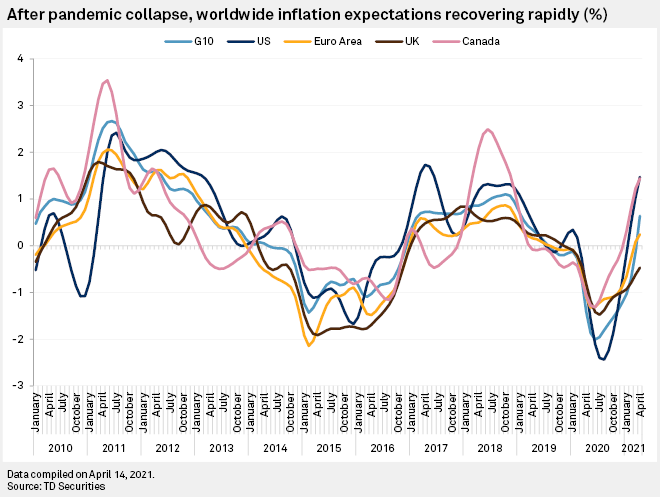

Inflation expectations have largely recovered globally, according to estimates from TD Securities which are based on roughly 100 different measures of inflation expectations across all G10 countries.

In the U.S., inflation expectations have reached 1.47% in April, up from 1.02% in March and up 390 basis points from the measure's trough in August 2020 when expectations fell to negative 2.43%. Inflation expectations are currently the highest they have been since May 2017 when they hit nearly 1.7%, according to TD Securities' estimates.

Fixed-income analysts had cautioned that a significant increase in inflation expectations could trigger a sizable run-up in bond yields, as a red hot economy in recovery could drive investors away from the relative safety of bonds to riskier markets, particularly equities. Bond yields move inversely to prices so a run-up in bond yields would indicate a corresponding decline in demand.

But bond markets have thus far shrugged off the latest inflation estimates, potentially due to fears about a rise in COVID-19 cases and issues over vaccine distribution. The market may also believe that the upward trend in inflation may be short-lived.

"The Fed and the administration have been putting on a full-court press to convince people that the rise in inflation is only temporary, and … the market seems to be convinced," said Marshall Gittler, head of investment research at BDSwiss Group.

Treasury yields had grown earlier this year, rising 106 basis points year over year as of April 5, before falling in the last few days.

"We're not 'inflationistas' by any stretch but we do think the bond market is getting too sanguine about inflation risks," said Win Thin, global head of currency strategy with private investment bank Brown Brothers Harriman, in an April 14 note.

The current rise in inflation is not only unique due to the unprecedented pandemic the global economy is attempting to emerge from, but because it will be moving with the Fed's policy to now allow inflation to run hot during the rebound.

"We seek inflation that is modestly above 2% for some time," Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said during an appearance at the Economic Club of Washington, D.C., on April 14. "That's our objective."

Powell has made this comment repeatedly since initially detailing the Fed's inflation stance in August, but he has yet to define what he means by "modestly," nor just how long "some time" might last.

"There's a lot of gray area until we can know exactly how they're going to react," said Eric Stein, chief investment officer with financial services firm Eaton Vance, in an interview.

Rather than specify inflationary benchmarks or dates when the central bank would work to end this policy, Powell stressed that his concern was over just how difficult it has been to get back to 2%.

The price index for core personal consumption expenditures, or PCE, which strips out food and energy prices and is the Fed's preferred inflation measure, was at 0.2% in February, down from 0.3% in January, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. March's PCE data is expected to be reported at the end of the month.

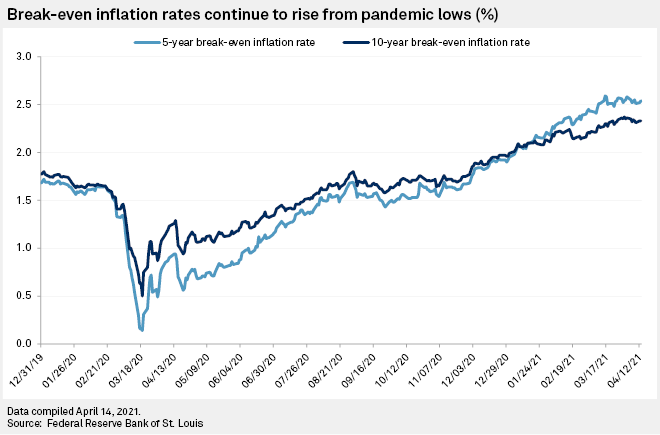

While bond markets have largely snubbed inflationary concerns this week, break-even prices — yields on regular Treasury bonds minus yields on Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities — have soared since dipping in March 2020 to their lowest levels since the 2008-09 financial crisis. The 10-year break-even rate, for example, settled at 2.33% on April 14, up 104 basis points from the same point a year earlier. The 5-year break-even inflation rate settled at 2.56% on April 14, up 162 basis points from the same point a year earlier.

This increase in breakevens is being driven by a "triple tailwind," said Rossiter with TD Securities, which includes creating scarcity through Fed monthly purchases of $120 billion in bonds, fiscal policy bolstering the recovering economy and the Fed's push to overshoot inflation.

"How much of that actually materializes is, of course, a very important question, and we'd argue that some of this will be temporary and it will take time for the Fed to achieve its target, in particular," Rossiter said.

But that target, Stein with Eaton Vance said, may ultimately prove to be little more than a temporary rise.

"I don't think the market fully believes in the Fed's average inflation targeting framework," Stein said. "They believe the Fed will be more patient than last cycle, but I don't think the market really thinks that the Fed is going to wait until we get there."