S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

13 Jan, 2021

By Brian Scheid and Polo Rocha

The short-term outlook for the U.S. economy may be dark, but bond investors see a bright future.

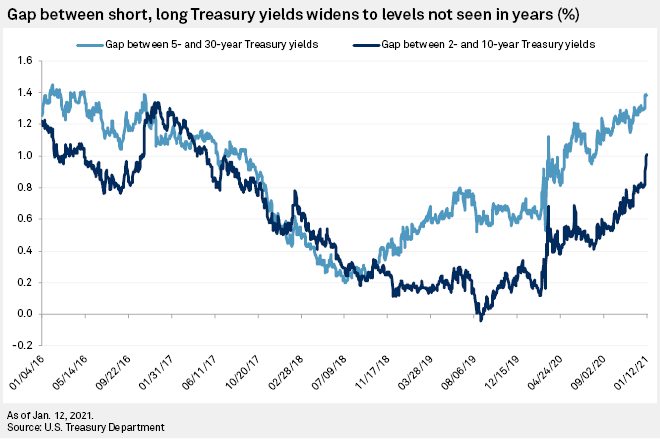

The U.S. Treasury yield curve has steepened to levels not seen since 2016, signaling that investors expect economic expansion and higher inflation in the coming years as coronavirus vaccines are distributed and incoming President Joe Biden and a Democrat-controlled Congress are expected to pass another substantial stimulus package.

The steepening curve is likely a sign of economic recovery, said Michael Crook, deputy chief investment officer at Mill Creek Capital. "It's very possible we're on track for a period of above-trend economic growth unlike anything we've seen in the last two decades, but it won't happen all at once."

The fly in the ointment could be the Federal Reserve, where regional presidents have begun weighing the possibility of reducing the bank's $120 billion in monthly bond purchases if the economy sees a boom later this year. Should the Fed stay on course, the yield curve would likely steepen further as short-term rates remain pegged as growth and inflation accelerate.

Nominal Treasury yields have moved in "near lockstep" with rates on Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities over the past week, an indication that the climb's main driver was growth expectations, Crook said.

Inflation expectations

A steep yield curve — when there is a large spread in interest rates between shorter-term Treasury bonds to longer-term bonds — often precedes a period of economic expansion, as investors bet that a central bank will be forced to raise rates in the future to tamp down higher inflation. The opposite is true of inverted yield curves, which suggest investors see the need for lower interest rates to prop up slowing inflation.

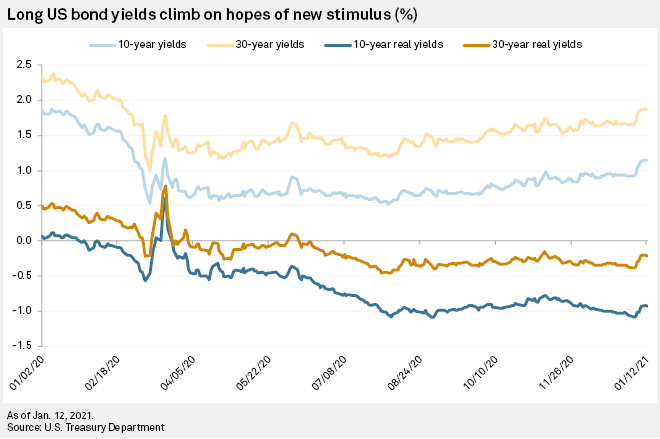

The U.S. Treasury 10-year yield settled at 1.15% on Jan. 12, up 19 basis points from Jan. 5, when Democrats won the races for Georgia's two Senate seats and tilted the balance of Congress. The 10-year yield has risen 34 basis points in the roughly two months since the U.S. presidential election and is now at its highest level since March 18, 2020, when the early days of the coronavirus pandemic caused wild swings in bond markets.

Yields on 10-year Treasurys should reach 1.5% by the end of 2021 as the rollout of the coronavirus vaccine, additional government stimulus and overall economic recovery expectations push long bonds' yields up in the first half of this year, Bruno Braizinha, a rates strategist with Bank of America Securities, said in a Jan. 12 note.

The 30-year yield has surged 32 basis points since November's Election Day, settling at 1.88% on Jan. 12, its highest close since Feb. 21.

Meanwhile, the gap between the five- and 30-year yields climbed to 138 basis points on Jan. 12, its highest point since November 2016. The gap between the two- and 10-year yields closed at 101 points on Jan. 12, its highest point since May 2017. Those gaps remained the same Jan. 12.

"The steepening signals that inflation expectations are rising," agreed Mike O’Rourke, chief market strategist at JonesTrading.

The 10-year breakeven rate, a measure of market inflation expectations, settled at 2.06% on Jan. 11, its highest level since November 2018.

The rise in inflation expectations, strategists said, will likely only reinforce the Fed's plan to keep interest rates lower for longer and try to run inflation above 2% to average out the years below that target threshold.

"The Fed states it won't do much until it is confident inflation will run above 2% for a period of time," O'Rourke said. "So for now, I don't expect them to take any action."

The Fed's preferred inflation gauge, the core personal consumption expenditures price index, rose by 1.4% in November 2020.

Patrick Leary, chief market strategist and senior trader at Incapital, said that in addition to more stimulus, which would be funded through borrowing, Treasury yields are also rising on optimism of a coronavirus vaccine and the release of pent-up demand later this year as social distancing mandates are eased or dropped entirely.

Fed far from a shift

Despite the recent rise, the 10-year yield remains at a historically low level. A 1.15% yield would be unlikely to impair growth nor impact Fed policy, Leary said.

"I don't think it is necessarily about a level that the Fed would consider shifting its bond purchases but more about the reason yields are rising, and what effect that rise is having on financial conditions and more specifically the stock market," Leary said. "If the stock market hangs in there, I don't expect the Fed to change from their current pace of bond purchases."

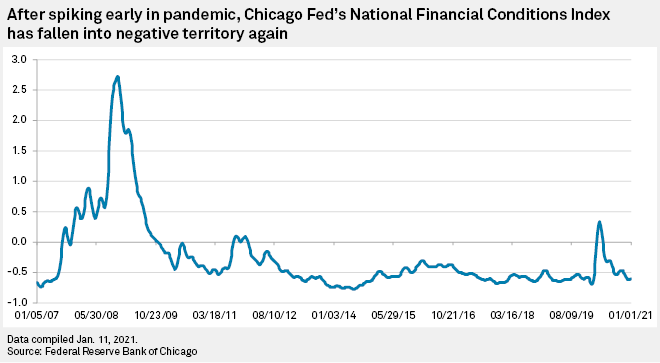

Financial conditions appear to be roughly the same as they were in mid-February, with the Chicago Fed's National Financial Conditions Index clocking in at -0.62. The weekly index measures risk, credit and leverage conditions in money markets, debt and equity markets and shadow banking systems. A negative value indicates that financial conditions are looser — borrowing and spending are easier — than average, while a positive value indicates tighter-than-average conditions. The index has fallen from a recent spike to 0.33 in early April, largely due to the Fed's accommodative monetary policies.

The Fed, in order to keep the economic recovery on track, needs to keep financial conditions loose, said Gennadiy Goldberg, senior U.S. rates strategist with TD Securities. An increase in real rates would signal tightening conditions and could draw a reaction from the Fed.

"There isn't an exact rubric on where the Fed would step into the market, but we think they would step in to prevent rates from rising excessively," he said. "If they rise too dramatically in a short span of time and if that increase is driven by expectations that the Fed would be less supportive to the US economy, we think the Fed would signal their displeasure and push back."

The 10-year real yield, which is adjusted for expected inflation, settled at -0.93% on Jan. 12, up 15 basis points in a week.

But Goldberg said it would like to take a 50-basis-point increase in real 10-year rates over several months to prompt a rethink of the Fed's policy stance.

"The Fed is keen to avoid repeating the Taper Tantrum of 2013, which set the recovery back significantly by prematurely tightening financial conditions," he said.

During a Jan. 8 presentation before the Council on Foreign Relations, Richard Clarida, the Fed's vice chairman, said he was "not concerned" about the 10-year yield's rise above 1%.

"The way that I look at the bond market and yields is: You have to try to understand why yields are moving up," Clarida said. "And if yields are moving up because people are more optimistic about growth, about a vaccine, are more confident, that we'll be able to achieve our two percent inflation objective, then that is not something that that that troubles me in the context of the overall picture."

Optimism about 2021 growth has also raised the prospects that the Fed could start to pull back the pace of its bond purchase program earlier than expected. The Fed is buying $80 billion in Treasurys and $40 billion in mortgage-backed securities each month.

Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic told Reuters on Jan. 4 that he hopes the central bank could "start to recalibrate" the program if the economy rebounds strongly later this year, a sentiment shared by a few other regional Fed presidents.

For his part, Clarida said his outlook suggests the Fed should keep the program as-is throughout the rest of the year. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell will also have a chance to push back on talk of an early tapering during a Jan. 14 appearance at Princeton University.

Crook with Mill Creek Capital said in spite of the potential spike in demand in the second half of this year and the likelihood of more fiscal stimulus from a Democratic Congress, unemployment remains well above full employment giving the Fed "plenty of breathing room" to keep rates near zero and its accommodative policy in place.

"I believe the mistakes of the last cycle loom large at the Fed, and they will be very cautious about restricting policy before it is absolutely necessary," Crook said.