S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

10 Nov, 2022

By Brian Scheid

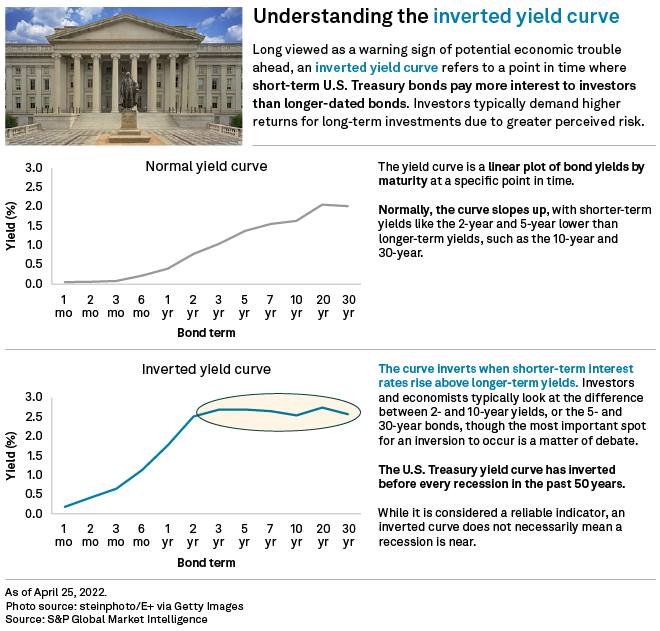

The cries of recession from the U.S. government bond market are getting louder.

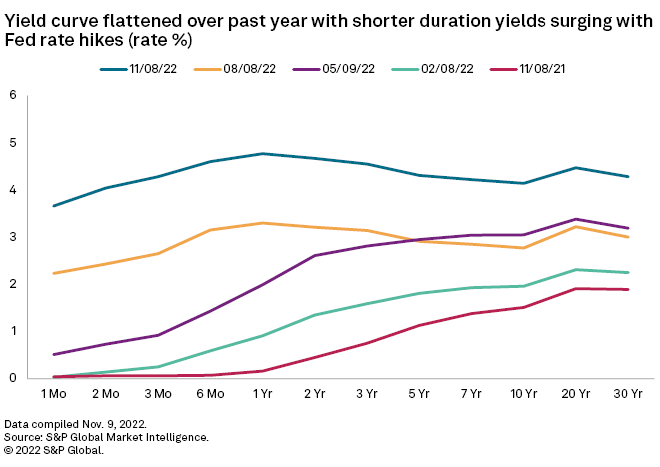

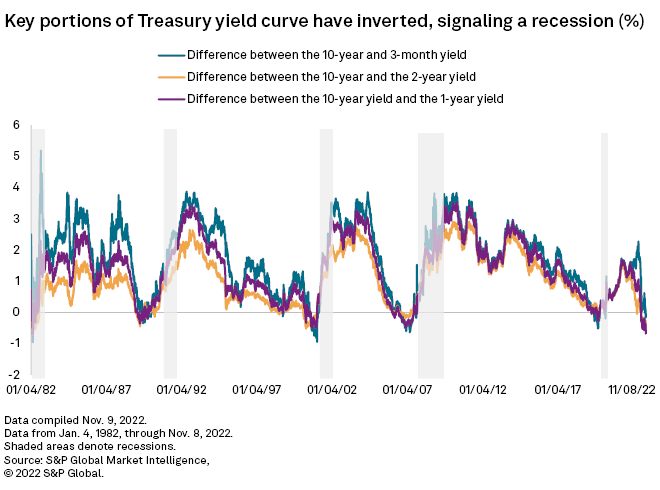

Shorter-term Treasury yields have skyrocketed more rapidly than longer-dated yields as the Federal Reserve has hiked rates at the most aggressive pace in decades in its push against soaring inflation. That has caused key portions of the yield curve to invert to levels not seen since the early 1980s, while the market's top recession indicator has fallen to depths not seen since the early days of the pandemic.

The yield on the 1-year Treasury bill, for example, has increased more than 460 basis points over the past year, compared to the 10-year yield, which is up just over 260 basis points. The sustained and faster rise of short-term bond yields relative to long-term yields reflects, at least in part, a market view that the Fed will need to loosen monetary policy in the future after current higher rates trigger an economic slowdown.

"Nothing is certain in these markets but yes, I think it is a strong clue of a recession ahead," said Antoine Bouvet, a senior rates strategist with ING.

'Forgone conclusion'

On Nov. 7, economists with S&P Global Market Intelligence revised up their real GDP growth projections for 2023 from -0.5% to -0.2% with a forecast for a mild recession, beginning late in the fourth quarter of 2022.

On Nov. 3, the 2-year Treasury yield was 57 bps higher than the 10-year, the most inverted that portion of the curve has been since 1982. On Nov. 1, the 1-year yield was 68 bps higher than the 10-year, also the largest inversion in about 40 years.

In addition, the 3-month yield has been higher than the 10-month since Oct. 25. Inversion between yields on those two bonds is viewed by many economists as the most accurate indicator of a coming recession.

This portion of the yield curve will likely need to remain inverted for at least two months in order for this to be a clear recession signal, said Beth Ann Bovino, chief U.S. economist with S&P Global Ratings.

"Daily inversions have too many false positives to say that it's a signal," said Bovino. "This is largely because daily rates are influenced by other factors, not just recession concerns."

With many portions of the curve already inverted for months, a recession may be a "foregone conclusion," said Gennadiy Goldberg, a senior rates strategist at TD Securities.

With the Fed expected to continue to hike rates into 2023, Goldberg said he expects some curve inversion to persist for most of the first half of next year.

"The curve tends to re-steepen only several months prior to rate cuts, so for the time being the curve may continue to languish in inverted territory," Goldberg said. "And the more harshly the Fed overshoots on rates to bring inflation down, the more likely the curve is to invert further."

Yield curve inversions will persist into 2023 and may not reverse until a recession forces a shift in monetary policy, said Bouvet with ING.

"The second half of 2023 will look different," Bouvet said. "A recession and a sharp drop in inflation should allow the Fed to contemplate cuts. This in turn should re-steepen the curve quite sharply, but we'll have to wait for a drop in inflation … which might take some time."