S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

11 May, 2021

Recovery in the labor market is the key to determining whether inflation will be temporary as unleashed consumer demand on the back of increased COVID-19 vaccinations is pressuring prices upward, economists say.

The massive supply of money created to counter a sharp drop in spending during the pandemic is making its way into the economy and has contributed to concerns that the economy will reheat as consumer spending increases.

The Federal Reserve is banking on a jump in inflation — albeit a transitory one — as one of many factors that will decide when to tighten its ultra-loose monetary policy. But while stimulus checks have boosted discretionary spending for poorer households, the effect will be temporary unless employment picks up.

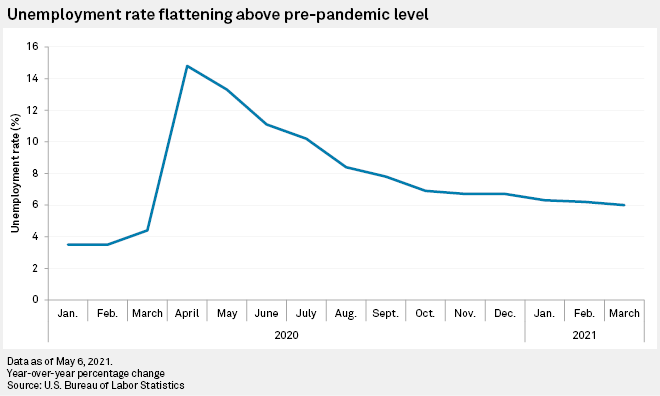

The U.S. remains well behind pre-pandemic job levels despite employment gains every month so far in 2021.

"Implicit is the Fed's belief that the massive slack in the U.S. labor market will keep structural inflation depressed," Dhaval Joshi, a strategist at BCA Research, said in an email, noting some 10 million people remain underemployed.

Surge in money supply

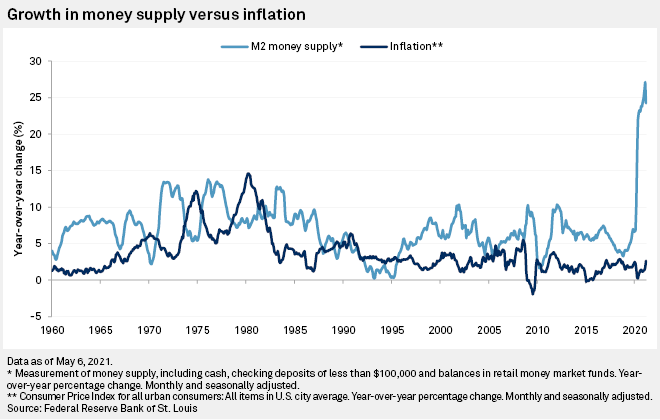

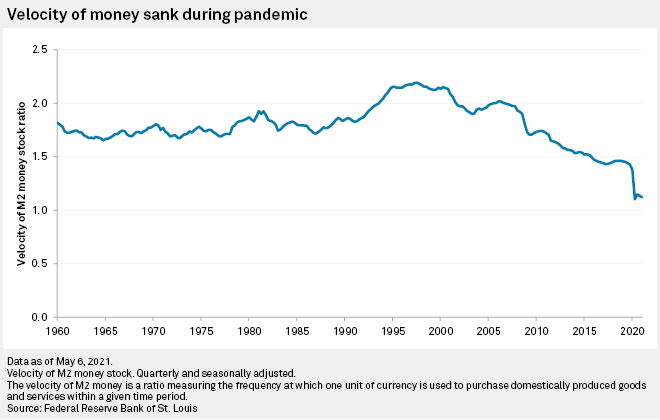

The injection of trillions in stimulus into the economy by the Federal Reserve and U.S. government have pushed up the supply of money to record levels, up 24.2% year over year in March to $19.896 trillion. So far, that increase has not pushed inflation up as its velocity — a measure of how often it is used to purchase goods or services within a period — sank to a record low of 1.1.

"If that money starts to circulate and velocity of money picks up, then inflation could follow — or so the theory goes," said Russ Mould, investment director at AJ Bell, in an email.

But America is spending again. Consumer expenditure rose 4.2% between February and March, supported by a record 21.1% monthly climb in personal income as stimulus checks arrived. This contributed to a 6.4% increase in GDP in the first quarter.

The increase in demand and higher energy prices boosted the consumer price index by 2.6% in March, an increase of 0.9 percentage points in a month. The core personal consumption expenditure price index — the Fed's preferred measure of inflation that strips out food and energy prices — rose 1.8% year over year in March after a 1.4% jump in February. The Fed wants the core price index to run at 2% over the longer term.

Bottlenecks in global supply chains have forced a rise in the price of key goods such as semiconductors, industrial metals and lumber, catching the attention of big business. The Procter & Gamble Co. and Berkshire Hathaway Inc. are among the companies warning that the prices of their products will increase.

"We're seeing very substantial inflation. It's very interesting. I mean we're raising prices. People are raising prices to us, and it's being accepted," Berkshire Hathaway's Chairman Warren Buffett told investors in a May 1 call with shareholders.

Warning signs that the economy will overheat has spooked investors, who are demanding higher yields for U.S. Treasurys in expectation of rising interest rates. The five-year breakeven rate — a closely watched measure of expected inflation — is up to 2.7%, the highest it has been since the build-up to the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

The Federal Reserve is insistent that the effects of the price rises will be transitory as bottlenecks in supply chains ease and the effects of the stimulus wear off. But others believe the inflation impact will be larger.

A temporary jump in the consumer price index to 6%-7% is possible and, importantly, a structurally higher level could be sustained, according to Martin Enlund, global chief FX strategist at Nordea Bank.

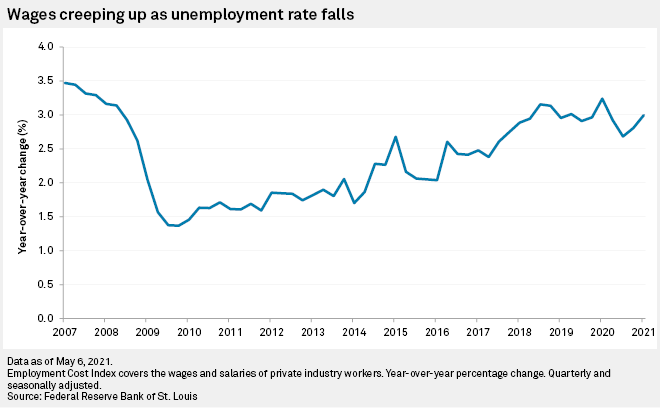

"To bring these inflation measures sustainably to 4% — as orthodox economists will see it — we probably need either a surge in wage growth or a drop in productivity growth. We would argue that we are likely to get a bit of both," Enlund said in an interview.

Labor market

Inflationary pressures on traveling and dining at restaurants have remained low during pandemic-related closures. Even as those pressures lift during reopenings and higher rates of travel, price increases in both categories will have limited impact.

Eating at restaurants contributes just 3.2% of the overall consumer price index inflation weighting, while airline fares count for just 0.6%.

Costs of shelter — primarily rent — contributes to 33.3% of the consumer price index basket and 42% of the Fed's favored core index.

Rents rise when a tight labor market pushes up wages, according to BCA Research's Joshi.

But that level is much higher than the 3.5% prevailing pre-pandemic, and Joshi expects structural changes in services sectors will mean many lost jobs will not come back.

It takes years for slack in the labor market to disappear after a recession, Joshi said. For example, it took four years for excess labor to be absorbed after the "dot-com bubble" in 2000, and that gap grew to six years following the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

Wage growth

Yet wage growth is accelerating. Private-sector wages rose 3% year over year in the first quarter, according to government data.

The Fed's own "Beige Book" reports, issued eight times per year, in addition to responses to business surveys offer evidence that labor shortages are triggering wage rises, according to Paul Ashworth, chief North America economist at Capital Economics.

"The focus has been on raw materials and intermediate inputs, but labor is also in short supply," Ashworth wrote in an email.

Ashworth said that while some people will be shielding from COVID-19, and others will be disincentivized from working due to enhanced unemployment benefits, a large number are retiring.

A tighter labor force and the desire of some Democrats in Washington to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 is also a growing concern for companies.

Structurally low inflation

Fears of a structural increase in inflation are misplaced, and mild deflation or price stability is "the steady state of any economy," Joshi said.

Double-digit inflation in the 1980s was an aberration caused by tight labor markets, an increase in unionization that gave labor massive bargaining power and a massive expansion of private debt, Joshi said.

"As long as we no longer have the rare star alignment that was the aberration, it is unlikely that we will have a structural inflation," Joshi said.

But others warn that inflationary signals will persist and the Fed will be forced to change its tune if the data continues.

"I'd argue that the April meeting may have been the last meeting in which the chairman could afford to be this dovish," Nordea's Enlund said.