Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

16 Mar, 2021

Wall Street has fallen in love with blank-check companies, which, in turn, love the technology, media and telecom markets.

|

This is the first installment of a three-part series focused on tech SPACs. The full series can be found here: Tech and SPACs: A dance of Wall Street darlings Tech and SPACs: Too much of two good things Tech and SPACs: Feeding the frenzy |

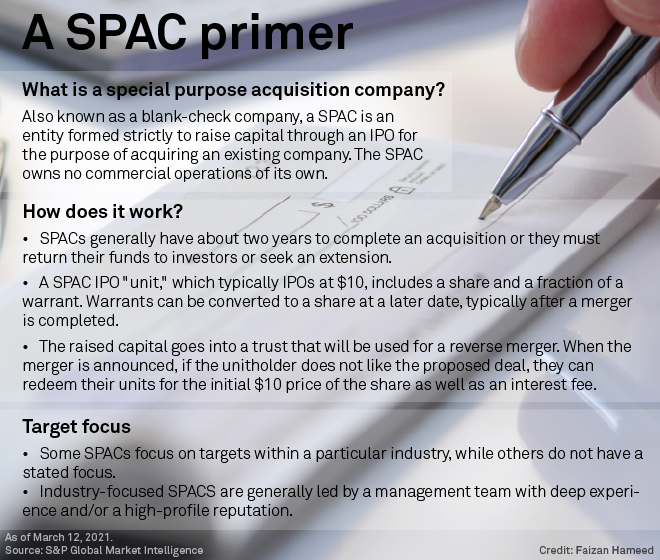

Blank-check firms, formally known as special purpose acquisition companies, combine a reverse merger with an IPO. A shell company launches an IPO with the expressed intent of using the funds to acquire an unspecified operating company. This allows the company to access public capital without having to undertake the highly regulated and scrutinized IPO process.

There are several benefits of the SPAC model over a traditional IPO or merger, and many are particularly advantageous for tech and media companies that need capital or a liquidity event. Those advantages are becoming clear to both investors and company executives.

Lion's share

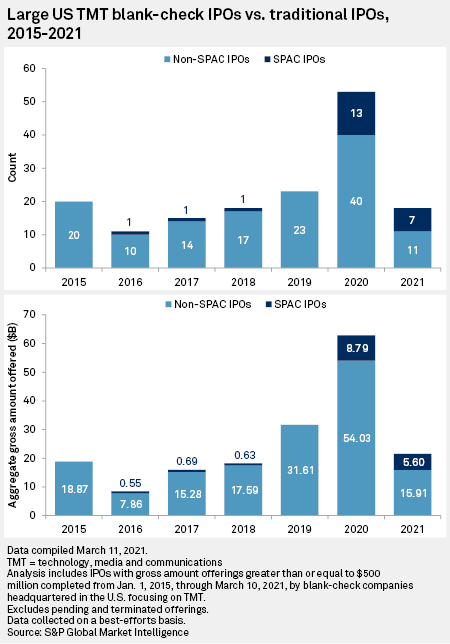

A third of SPACs listed in 2020 and another third of those listed in 2021 target the technology, media and telecom, or TMT, industry, an outsized share compared to other industries.

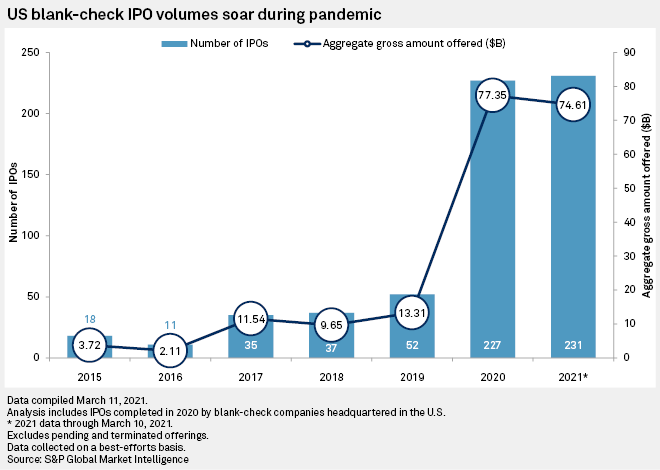

That outsized portion of TMT SPACs comes amid record SPAC activity overall. Less than two-and-a-half months into 2021, there have already been more SPACs listed this year than in all of 2020. Moreover, 2021 is on pace to break 1,000 SPAC IPOs. That would be roughly quadruple the number of 2020 SPAC listings, which roughly quadrupled the number of 2019 SPAC IPOs, said Jay Ritter, finance professor at The University of Florida.

U.S. stock exchanges have never registered 1,000 IPOs of any variety in a single year, he said, much less though SPACs specifically.

By his count, at the end of February, there were over 300 SPACs that had listed on the public market but had not yet identified a merger partner. SPACs generally have between 18 and 24 months to complete a merger. Otherwise, it must return the raised funds to investors or seek an extension. The sheer volume of SPACs is what makes the current pace unsustainable, Ritter said.

"At a point, there's a limit of how many companies out there are suitable for the public markets," said Scott Denne, an analyst with 451 Research, an offering of S&P Global Market Intelligence. "It's hard to imagine that number increasing."

Tick, tick ... boom!

Just the frenzied pace at which sponsors are launching SPACs, some listing multiple tickers on the same day, suggests a recognition that there is a limited number of targets for which to compete, Denne said.

Rajiv Shukla — chairman and CEO of SPAC Alpha Healthcare Acquisition Corp., which recently announced a merger with Humacyte Inc. — encouraged investors to discriminate between various types of SPACs and their fundamentals. But he does not believe all SPACs will be punished for the current exuberance, or that there is a bubble to be popped. The run-up in SPAC activity is not just retail investors looking to Reddit for the latest craze, as some outlets have reported. Rather, it is being driven by savvy institutional investors using the same discretion they would for any market entry.

"SPAC IPOs and SPAC [private investments in public entities] are institutional investors, and there is a lot of rationality at IPO and at PIPE," said Shukla, who is also a partner with tracking and data platform SPAC Research. The PIPE he referenced refers to a private share offering often initiated by a SPAC to raise additional capital ahead of a proposed merger.

But Shukla noted the amount of speculation between IPO and a merger-related PIPE has indeed reached a frenzy. To illustrate, the first-day return on the average SPAC before 2021 was about 1%. A low first-day return is reasonable given that investors are not yet aware of what the shell company will become, as a merger has not been announced. However, in the early months of 2021, that first day return has grown to 6%, Ritter at the University of Florida said.

For Shukla, that retail speculation does not change the fact that savvy professional and institutional investors are seeing something valuable in the SPAC model and taking on the typical $10 IPO entry with measured enthusiasm.

"I'm not relying on retail investors," the executive said, noting that retail investors account for less than 5% of SPAC IPO investors.

The value of growth

For TMT, and for the tech sector in particular, there are a few reasons the SPAC model is attractive to both companies operating in the sector and investors looking for returns. But the top reason for tech's outsized share of the SPAC boom, and the top reason for risk in the tech SPAC space in 2021, boils down to one word: growth.

|

Creating and deploying new technologies is by nature a speculative business. Tech companies often operate around a business model and capital structure that does not generate revenue or profits for years, but rather depends on market projections and forward-looking guidance to raise funding. In contrast, the SEC strictly limits forward-looking guidance in IPO filings in an attempt to encourage valuation and investment on past financial performance.

When past financial performance is in the red, as it is for many tech companies, an IPO conversation is a nonstarter.

However, in many tech and media sectors, pre-revenue companies need IPO levels of capital, having drawn everything they can from private seed and series investors.

Enter the SPAC, a way to go public through a merger, which provides a path to valuation based on forward-looking projections. Also, an M&A deal typically occurs much faster and with less regulation than the IPO listing process.

"It opens the door for different kinds of companies," 451's Denne said in an interview, referring to young tech firms.

It can be a way of democratizing the growth-capital investment model, which has historically been the purview of venture capital, hedge funds and other private equity firms that can offer large rounds of financing without the SEC regulations restricting public listings.

Under the SPAC model, everyday retail investors can pitch in on a Silicon Valley tech play for their own crumpled $10 bill. After buying a SPAC IPO "unit," which typically sell at $10 apiece and come with a fraction of a warrant, a unit-holder retains the right to redeem their units for the initial $10 price of the share as well as an interest fee if they do not like the deal the SPAC ultimately pursues.

So a tech SPAC trader is potentially buying into a risky deal and an unproven technology and does not have the regulatory assurance of a traditional IPO, but they also have the option to trade out with interest once the deal terms are outlined. Thus, the SPAC model is a derisked way to play in what has conventionally been a private equity market for speculative growth companies, and few industries do speculative growth like tech.