Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

15 Nov, 2021

| An LNG tanker enters Rotterdam harbor to dock at an LNG terminal. |

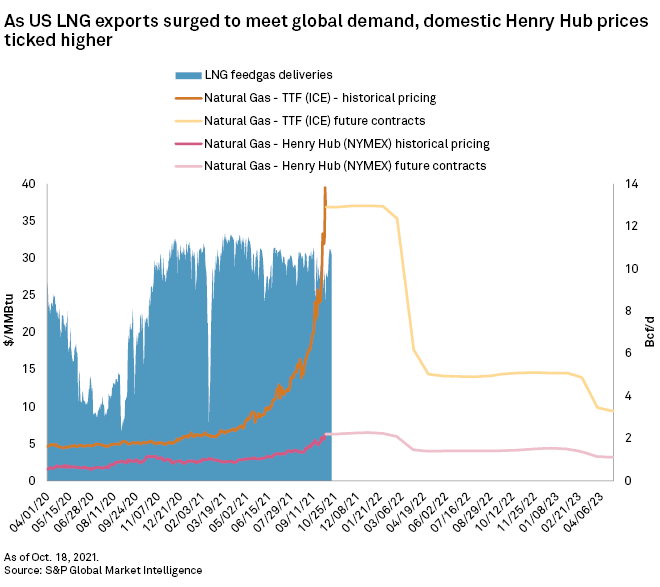

U.S. LNG export facilities continue to run at full throttle as a tight global market sends domestic natural gas prices to their highest level in years.

World buyers are desperate to find available LNG cargoes, sending prices skyrocketing during a global energy crisis triggered by a combination of factors, including a gas shortage as global demand rebounds from the pandemic. The U.S., which over the past five years has become one of the top three LNG producers in the world, is no longer immune to price spikes in the global gas market.

Natural gas experts say the U.S. may have reached an inflection point in its rise as an LNG producer, where exports are not just an outlet for a glut of domestic natural gas but a driver of higher prices. At the same time, U.S. gas producers have refrained from increasing output in response to the price signals, largely complying with investors' demands.

The run-up in prices has fueled a fresh debate about the role of LNG in U.S. markets and as a fuel in the broader energy transition.

"Gas as a transition fuel makes a lot more sense when gas is cheap and available," Erin Blanton, a senior research scholar at Columbia University's Center on Global Energy Policy, said in an interview. "But if it's 30-plus dollars [per MMBtu], and you are not getting enough of it, it probably exacerbates the view that it is not reliable, for the Europeans in particular."

The European benchmark Dutch Title Transfer Facility day-ahead contract reached an all-time high of $39.51/MMBtu on Oct. 5, while the S&P Global Platts Japan Korea Marker spot Asian LNG price hit a record high of $56.33/MMBtu on Oct. 6. Prices have dropped since then, but they remain several times higher than prices in the U.S. and continue to encourage U.S. LNG exports.

U.S. benchmark Henry Hub natural gas prices closed at just under $5/MMBtu on Nov. 9, a drop from earlier in the week but still up from about $2.86/MMBtu a year earlier.

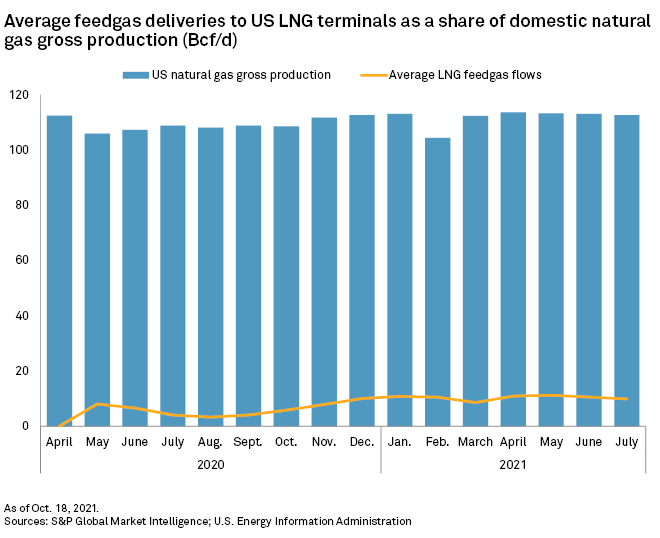

Total gas deliveries to the six major operating U.S. LNG export facilities were about 11 Bcf/d on Nov. 9, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence pipeline flow data. This compared to about 10 Bcf/d in feedgas flows to U.S. terminals at this time in 2020 after sector activity recovered from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the U.S., high gas prices have prompted some power plant owners to consider ramping up other sources of generation such as coal. Federal regulators have warned of potential price spikes and supply shortages in the Northeast. The U.S. Energy Information Administration forecast that U.S. households relying on natural gas for heating will see bills that are 30% higher on average from last winter. Wall Street, meanwhile, expects U.S. natural gas utility operators will see earnings suffer.

The gas crunch

In Europe, surging gas prices sent power prices to record highs in the third quarter, triggered government interventions to curb electricity bills and caused some gas-intensive industrial users to slow down production.

A shortage of gas supplies is not the sole reason for the energy crisis abroad, with issues such as lower-than-expected offshore wind production in Europe also playing a role. But the gas crunch is a key factor.

A cold winter left gas storage levels low at the start of 2020. A warm summer increased demand for some gas that might have otherwise been stored.

"The killer one has been the European inventories," Jason Feer, head of business intelligence at Poten & Partners, said in an interview. "Because that has basically meant that no matter what else happened in the world, you were always going to have a very motivated buyer."

A series of minor production outages at world LNG export facilities from the Gulf Coast to Australia also contributed, while strong gas demand led to a competition for supplies in recent months between buyers in Asia and Europe. It was a "tug of war" that "exposed the supply constraints facing the industry in the wake of the pandemic," Cheniere Energy Inc. Executive Vice President and Chief Commercial Officer Anatol Feygin said during a Nov. 4 earnings call.

Exporters have said high global gas prices show a need for buyers to secure LNG supplies under long-term contracts and demonstrate that there is sufficient demand to build new export facilities. And some U.S. developers have benefited from an uptick in contracting activity.

"If it gets to be a cold winter, prices go high and people start to blame exports for high prices, then you could see pressure for some sort of relief or some sort of mechanism that would prioritize U.S. supply over exports," Feer said. "And right now, the only real mechanism is just price."

Drillers hold the line

U.S. LNG exports are not the sole reason for the run-up in domestic prices, although the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission flagged a 21% year-over-year growth in LNG exports as a primary driver. Production impacts from Hurricane Ida, increased consumption in sectors other than the power sector and lower-than-average storage levels have all contributed.

But another critical factor is investor pressure on U.S. oil and gas companies to focus on financial discipline instead of increasing output. Major shale oil and gas drillers including EQT Corp., Chesapeake Energy Corp. and others reported a boost to their free cash flows from higher gas prices in the third quarter, but they vowed not to spend the money on production growth.

"We need more than just short-term price signals" to increase production, EQT President and CEO Toby Rice told investors during a recent earnings call. "We need to see that we've got long-term demand for our product."

In the meantime, the U.S. LNG industry faces an effort by industrial manufacturers to convince the U.S. Department of Energy to order U.S. LNG producers to limit exports to avoid winter price spikes and supply shortages. The leading U.S. LNG trade group argued that curbing exports could upend gas markets and undermine billions of dollars worth of infrastructure investments.

ClearView Energy Partners analysts described a "minimal, but non-zero, policy risk" to LNG exports in a note to clients but said DOE intervention is unlikely. Diplomatic concerns and judicial challenges could deter the White House even in the case of an acute and sustained gas shortage, the analysts said.

U.S. President Joe Biden said Nov. 10 that his economic team continues to pursue ways to reverse rising energy costs, but the administration so far has not suggested it would move to reduce U.S. LNG exports.

"There's a natural gas shortage around the world, hence the need for the United States to continue to export natural gas," White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said Oct. 13.

S&P Global Market Intelligence and S&P Global Platts are owned by S&P Global Inc.