Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

4 Oct, 2022

| California Attorney General Rob Bonta speaks during a news conference outside of an Amazon distribution facility on Nov. 15, 2021, in San Francisco. |

State politicians impatient with the pace of federal movement on Big Tech antitrust concerns are likely to follow California in using their own laws and resources to take action, policy experts said.

While divided federal government bodies often have difficulty finding consensus on matters like Big Tech antitrust cases, state governments in many cases are less divided and more able to step in, the experts said. A lawsuit filed last month by California Attorney General Rob Bonta, for instance, alleges Amazon.com Inc. violated two state business competition laws in requiring third-party sellers and wholesalers to offer the lowest prices for their products on Amazon. The California suit further claims that Amazon hurts sales of those who do not comply by declining to promote their Amazon listings.

Amazon said its practices are intended to ensure that it is highlighting the lowest prices available for its customers.

"Sellers set their own prices for the products they offer in our store," a company spokesperson told S&P Global Market Intelligence in an emailed statement. "Amazon takes pride in the fact that we offer low prices across the broadest selection, and like any store, we reserve the right not to highlight offers to customers that are not priced competitively. The relief the AG seeks would force Amazon to feature higher prices to customers, oddly going against core objectives of antitrust law."

Policy experts said more states with antitrust laws and politically ambitious attorneys general are likely to utilize state-level legislation to address Big Tech concerns.

"The politics reward people who show that they are pushing to make Big Tech accountable, and that makes it an attractive issue for state attorneys general," said Matt Perault, director for the Center on Technology Policy at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and a policy adviser with New Street Research.

State levers

Perault pointed to states like Texas, New York and Colorado as among those most likely to pursue their own cases against Amazon.

Similarly, William Kovacic, a former FTC chair and a current law professor at George Washington University, said states such as New York and Maryland that have their own antitrust divisions and laws are likely to consider filing cases against Amazon.

The Maryland Antitrust Act, for example, prohibits price-fixing and attempts to monopolize. A spokesperson for Maryland's attorney general said the state does not comment on potential litigation. New York's Donnelly Act prohibits price-fixing and monopolization practices, while Colorado's antitrust law makes attempts to monopolize illegal. The offices of attorneys general for both states did not respond to inquiries for this story.

District of Columbia Attorney General Karl Racine filed a lawsuit against Amazon similar to the suit filed by California. Though the suit was dismissed this year, the Washington, D.C., attorney general's office is appealing the dismissal.

Leader of the pack

California's state-level regulations give it an advantage when it comes to enforcement actions against Big Tech.

California can use its state policy tools to prove a theory of harm that claims Amazon is denying firms that do business with the company the opportunity to pursue relationships that give them the ability to reach customers on other websites, Kovacic said. "It's the demand for exclusivity — basically saying if you want to use our formidable platform, you can't avail yourself of alternatives that offer users a better deal than our platform," Kovacic said.

Developer Epic Games Inc.'s lawsuit against Apple Inc. last year cited California's Unfair Competition Law in claiming Apple's "anti-steering" restrictions were anticompetitive. The restrictions forbade app developers from informing users about other payment mechanisms. A district court judge sided with Epic on that point and ordered Apple to allow mobile developers to offer other payment options.

"California has a broader range of policy tools it can use, and the Epic case is a good example of a recent application of one of them," Kovacic said. "It's a more favorable environment for the AG's office to pursue the case."

Pricing business

California's lawsuit against Amazon also cites the impact of the platform charging high fees to third-party sellers. The suit says those fees lead sellers to protect their margins by raising prices, which in turn leads to higher prices on other platforms due to Amazon's practices regarding promoting only those products with the lowest advertised prices.

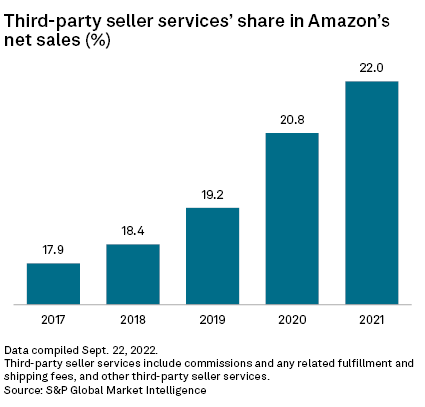

Amazon's third-party seller services, which include fees collected from merchants for each item sold as well as shipping fees, accounted for 22% of Amazon's total net sales of $469.82 billion in 2021, up from 17.9% of net sales in 2017.

Jason Boyce, a former Amazon seller who now serves as a consultant for seller brands, described the impact of Amazon's pricing and promotion practices on one of his former clients. The client's pill dispenser product was a top-seller on Amazon.com but saw sales fall 30% after the dispenser was listed for less at Walmart Inc. The seller ended up removing the product's listing from Walmart, Boyce said.

Boyce is the founder of Avenue7Media, which manages third-party private label seller brands on Amazon.

Boyce said Amazon's practices are "raising prices on the internet, and it's also suppressing marketplace competition."

Boyce said he experienced this first-hand as a seller after he cross-posted products on eBay Inc. and Wayfair Inc. He soon saw sales for the cross-posted goods drop sharply on Amazon.com. This occurred after Amazon removed a pricing parity clause that prohibited sellers from offering products for lower prices elsewhere.

"I got excited for a minute, thought I could diversify my sales a little more with lower prices on lower cost marketplaces," Boyce said. "I went right back to raising my prices everywhere else to matching Amazon's."

Adam Kovacevich, founder and CEO of the tech policy coalition Chamber of Progress, defended Amazon's practices, saying consumers benefit from Amazon's policy of featuring products with the lowest prices. The Chamber for Progress has roughly 30 members, including Amazon, Meta Platforms Inc., Apple and Google LLC.

"No merchant is required to sell their goods on Amazon; if they want to sell their goods on Amazon, Amazon can decide which offer is going to be featured," Kovacevich said.