Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

31 Aug, 2022

By Matt Smith and Cheska Lozano

Banks in South Africa are likely to face difficulties, as well as higher costs, doing cross-border business and attracting foreign investment should the country fail to meet international anti-money laundering benchmarks.

South Africa's government is drafting amendment bills designed to prove to global financial bodies that it can fight money laundering, after the Financial Action Task Force, an intergovernmental body tasked with combating financial crime, flagged money laundering and terrorism risk failings in the country and placed it in a one-year observation period that ends in October.

The South Africa Reserve Bank, or SARB, for its part, has instructed banks to review their operations and is conducting monthly sessions to help them rectify deficiencies, a spokesperson for the central bank said. There was a "high" likelihood that South Africa would be included in FATF's so-called gray list of countries that are subject to increased monitoring, the regulator said in a May financial stability report.

FATF declined to comment on South Africa's case, as it is ongoing.

Higher costs for banks

South Africa's potential inclusion in the gray list would lead to higher transactional, administrative and funding costs for the country's banks, while restrictions on cross-border transactions could impact imports and exports and ultimately gross domestic product, SARB said in the May report.

A spokesperson for Standard Bank Group Ltd., the country's largest lender, said South Africa's corporates, including banks such as Standard Bank, "would in general become a 'harder sell' to potential international clients, investors and correspondent banks."

"We would face far more questions about whether it would be reputationally and legally safe to trade with us, and some investors would be likely to withdraw," he said.

When a country is added to FATF's gray list, capital inflows decline by an average of 7.6%, and foreign direct investment by 3.0%, according to a 2021 IMF report.

Such a change "would cause material reputational damage to South Africa's financial system, hamper investment and international financial transactions in the country" and could lead to a further downgrade of its credit ratings, a spokesperson for Nedbank Group Ltd. said.

Banks' ability to conduct cross-border transactions would be restricted, and this could lead to higher compliance and due diligence costs for Nedbank's clients, the spokesperson said.

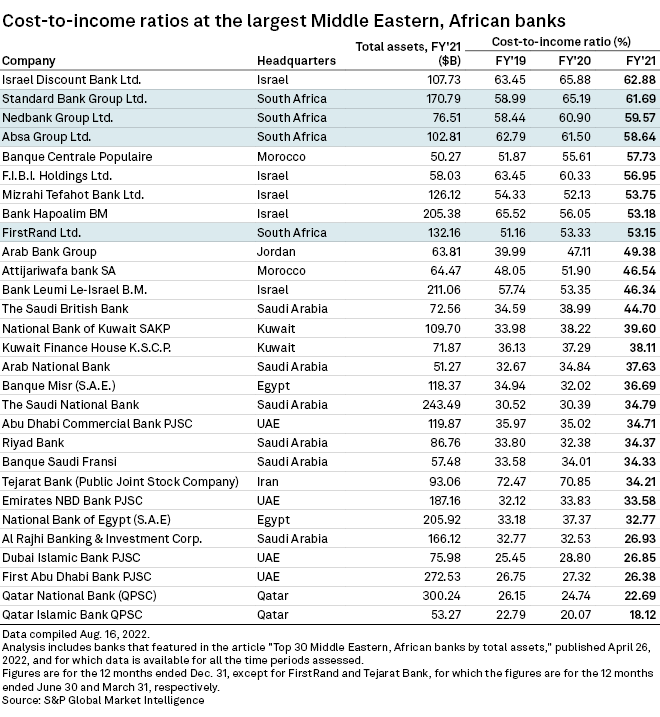

South Africa's banks already shoulder high costs. Standard Bank's cost-to-income ratio was 61.69% at the end of 2021, the second highest among large banks in the Middle East and Africa. Nedbank's ratio was third highest and Absa Group Ltd.'s ratio was fourth highest.

"For a corporate in a gray-listed country, everything slows down, gets more expensive, and more uncertain," the Standard Bank spokesperson said, highlighting how colleagues based in certain gray-listed countries endured considerable difficulties.

"They face a lot more red tape — higher compliance costs, more audit requirements, and longer delays — in what should be simple matters like getting letters of credit, clearing foreign payments, and even just establishing relationships with would-be foreign suppliers of inputs and purchasers of their products."

The rand would fall sharply and growth would "grind to a halt," in turn prompting higher inflation, unemployment and poverty, the spokesperson said.

South Africa loses up to $25 billion in illicit financial flows annually, according to reports citing data from state agency the Financial Intelligence Centre, which declined to confirm whether it had made this estimate.

Banks respond

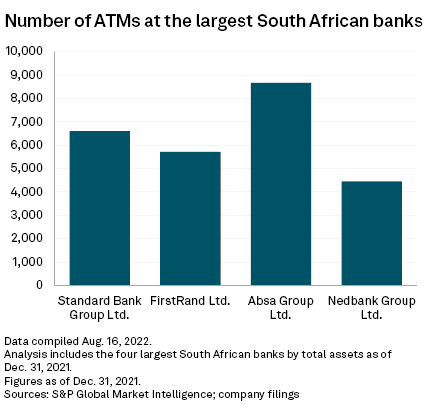

Standard Bank, FirstRand Ltd., Absa, Nedbank and Capitec Bank Holdings Ltd. hold 89% of the sector's deposits. They are vulnerable to inadvertently enabling financial crime due to their large number of clients with unknown citizenship, links with other countries and "very high" exposure to cash deposits, with criminals using ATMs to deposit cash anonymously, SARB said in a July banking sector risk assessment report. Standard Bank, FirstRand, Absa and Nedbank have between 4,400 and 8,700 ATMs each, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data.

Standard Bank has undertaken a companywide risk assessment and enhanced internal controls where this was deemed necessary, and it is satisfied it meets FATF standards, the bank's spokesperson said. It is upgrading its financial crime detection tools to leverage artificial intelligence and has hired additional analysts over the past two years to identify suspicious activity. The spokesperson declined to quantify how much these measures had cost.

Absa told Market Intelligence that it already complies with international anti-financial crime standards and regulation, as required in order to access global financial markets.

Nedbank's risk management and compliance program meets international standards, its spokesperson said.

"This is a highly complex, high-volume environment, and while we, and other banks, are likely to make some administrative errors from time to time that require remediation and attract regulatory scrutiny and so a risk of penalties, we are confident that our risk management and controls to combat actual money laundering and terrorist financing are robust," the spokesperson said.

FirstRand and Capitec did not respond to requests for comment.

"South Africa has an existing infrastructure around anti-money laundering and customer beneficial ownership reporting, but could banks enhance that capability? Yes, they could," Daniel Masvosvere, a senior equity analyst at Ashburton Investments in Cape Town, said in an interview with Market Intelligence. A material increase in banks' operational expenditure on their compliance departments is unlikely, however, as there is ongoing investment there, he said.

Banks are not the only actors in the chain; the regulatory and legislative framework also needs to be more robust, Masvosvere said.

Foreign banks

Foreign lenders such as Citigroup Inc., HSBC Holdings PLC and Standard Chartered PLC operate in South Africa, offering high-risk products such as trade finance.

"Banks can seek to reduce the risk associated with such products through implementing stringent controls and customer due diligence processes, ensuring that effective ongoing due diligence and transaction monitoring are performed and that it clearly understands its clients, the expected transactional activity as well as the nature of the business and intended purpose of the business relationship," the SARB spokesperson added.

Foreign banks are unlikely to exit South Africa immediately should the country join FATF's gray list, said Thato Mashigo, portfolio manager at Johannesburg's Sanlam Private Wealth.

"Is the government ratifying the required policy amendments, are regulators acting swiftly to enforce breaches, and are banks improving their internal policies? If these questions are answered positively, then foreign banks will remain," he said.

FATF removed Mauritius from its gray list last October, 20 months after the island nation was added, after it implemented various reforms requested by the agency.

"If South Africa is able to respond in a similarly prompt fashion, then the gray listing will be temporary and therefore not too onerous financially," Mashigo said.

South Africa is noncompliant with five FATF recommendations and fully compliant with only three, according to U.K.-based financial crime technology platform and consultancy Themis.