Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

15 Mar, 2021

By Brian Scheid

The latest bond sell-off probably will not push the Federal Reserve off its policy holding pattern, but a big hit to stocks could trigger a change in course, fixed-income strategists say.

"We expect any drastic move in [bond yields] upward that spooks the equity markets will cause the Fed to change their tune," said John Luke Tyner, a fixed-income analyst at Aptus Capital Advisors, in an interview.

Even the chance of a signal of policy change from the Fed will likely depend just how much rising bond yields drag on equity markets. But just how much of a drag the central bank may endure and for how long remains a mystery.

"With the Fed being comfortable with the rise in yields, traders are left to wonder when will they be uncomfortable with it?" asked Patrick Leary, chief market strategist and senior trader at Incapital, in an interview. "If the equity markets continue to hang in there, or trade sideways, or even rally a little bit you won't see a change. If the economy is really roaring and 10-year notes get to 2% that's probably ok."

As an ongoing selloff in bonds and dip in tech stocks rages on, there has been no indication that the Fed is even considering a change from its ongoing policy, including purchases of $120 billion in monthly assets and keeping rates near zero. No policy shift is expected from the Fed's monthly policy meeting March 16-17.

And while speculation has surfaced in some fixed-income circles that Fed officials may eventually weigh initiatives such as a return to Operation Twist, under which the Fed would attempt to lower long-term rates by selling near-term bonds and buying longer-dated ones, or yield curve control, those efforts are not under any serious consideration in the near term.

"Fed officials are unlikely to see much of a problem at a time when financial conditions remain easy, activity is picking up, and powerful growth impulses are set to support the economy all year," Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs, wrote in a March 14 note.

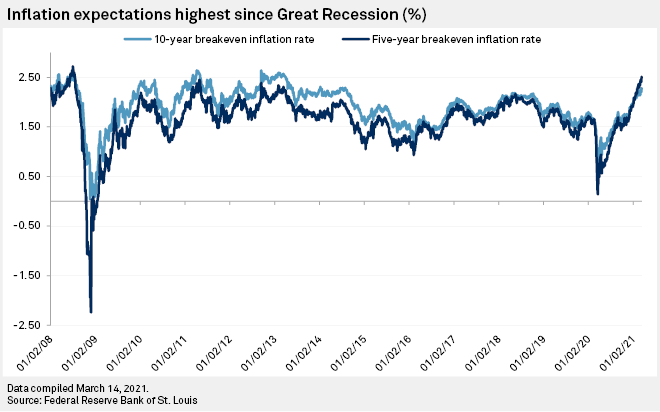

But that economic optimism has been soured by investors' growing views that the rapid rise in the yield signals excessive inflation on the horizon and tighter monetary conditions. The five-year breakeven inflation rate, a rough measure of the bond market's view of inflation over the next five years, closed on March 12 at 2.51%, the highest point since July 2008.

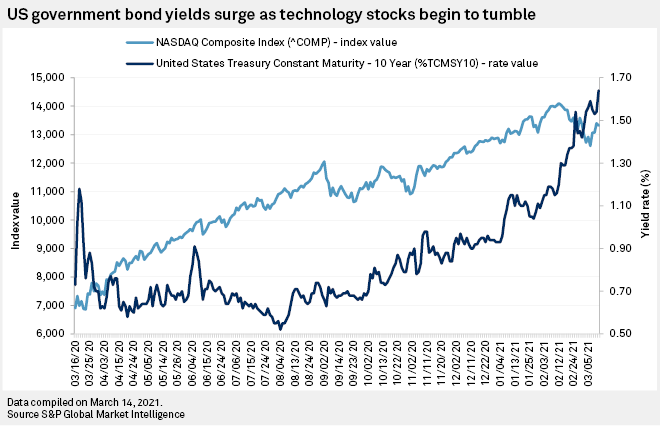

The benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury yield, which moves inverse to bond prices, settled at 1.64% on March 12, its highest close since February 2020 and a 71-basis point jump since the end of last year.

The surge has triggered a rotation from growth to value stocks and corresponded with a decline in tech stocks. The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite Index settled March 12 down 5.5% from its Feb. 12 close.

According to Leary, a potential bond-motivated shift in Fed policy has less to do with how high yields go than how fast they get there. Potentially, if yields continue to rise rapidly, the surge could cause a significant decline in stocks.

Still, with bond yields continuing to climb, Leary said it remains unclear just how much faster the rise in yields would need to be in order to push the Fed to act.

"You'd think the move we had would've been swift enough," he said.

If the bond market sell-off takes the 10-year Treasury yield above 1.7%, the Fed may contemplate increasing its government bond purchases or extending the supplemental leverage ratio, or SLR, exemptions, which expire at the end of the month, according to Ed Moya, a senior market analyst with OANDA.

"The Fed has tools to act, but they will first try to talk down markets," Moya said in an interview. "The economic recovery and outlook justifies a steeper yield curve, it is the trajectory that is concerning policymakers."

In a March 12 note, James Knightley, chief international economist with ING, said he expects the SLR exemptions to be extended by the Fed.

"But, if the Fed were to choose not to extend, then there could be repercussions," Knightley wrote, including selling more than $600 billion of U.S. bank holdings of Treasuries.