S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

3 Aug, 2022

By Stefan Modrich and Joseph Williams

Global demand for high-end computing chips is leading to more focused deals and partnerships in the semiconductor industry.

Several attempts at blockbuster deals failed in recent years due to regulatory concerns regarding competition and national security. With major consolidation off the table, analysts say smaller transactions will become the norm, alongside increased industry collaboration.

"There are so many landmines out there in the M&A world of semiconductors that I think the big companies that are interested in mergers and acquisitions are a little bit gun shy about trying to buy somebody outright," said Mike Paxton, a senior analyst with Kagan, a media research group within S&P Global Market Intelligence. "Mostly what you're seeing are large companies taking over smaller companies for some specific capability ... or facilities that a company may have."

Chips off the table

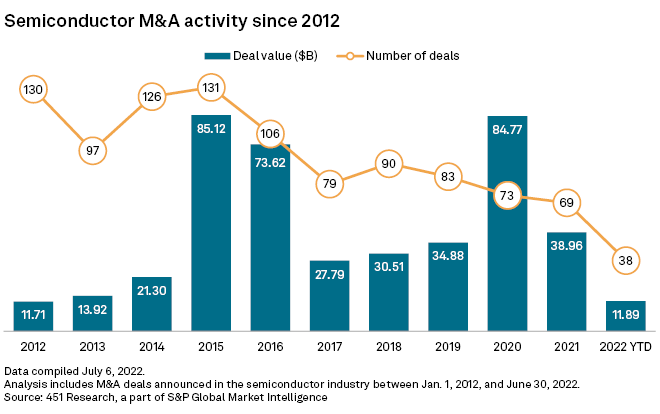

With industry scrutiny increasing, semiconductor deal volume has fallen over the past decade. Sixty-nine deals were announced last year, down from 130 in 2012, according to data compiled by 451 Research.

Government officials around the world increasingly view the protection of intellectual property held by semiconductor manufacturers as crucial to national security, said Chris Grey, a U.K.-based TMT M&A lawyer at Clifford Chance. In recent years, U.K. and U.S. regulators have blocked mergers and acquisitions involving companies with alleged links to the Chinese government.

The sector's largest terminated deal to date is Broadcom Inc.'s 2018 withdrawal of its offer to buy QUALCOMM Inc., a transaction valued at $102.69 billion when it was announced. The deal fell through after then-U.S. President Donald Trump moved to block it based on national security concerns. At the time, Broadcom was based in Singapore.

Regulatory resistance also contributed to the termination of another large semiconductor deal this year: NVIDIA Corp.'s $38.59 billion offer to buy Arm Ltd. from SoftBank Group Corp..

Unlike NVIDIA, which sells chips and hardware directly, Arm generates its revenue from licensing and royalty fees paid by third-party companies that use its patented chip designs in their own proprietary hardware.

"[NVIDIA's] licensees often have to share really competitive and sensitive information with Arm," said 451 Research analyst John Abbott. "If NVIDIA owned [Arm], that would have been really awkward for them to manage."

Because a wide range of companies and governments depend on Arm's designs, global regulators were reluctant to allow a combination with another semiconductor company, said Grey.

After the NVIDIA deal fell apart, Arm parent company Softbank changed strategies to focus on an initial public offering for the chip designer. Chipmaker Qualcomm has also expressed interest in buying a stake in Arm, potentially as part of an investment consortium if necessary to allay regulators' concerns about competition.

Spokespersons for Qualcomm and Arm declined to comment.

Intel Corp., one of the few semiconductor companies that designs and manufactures its own chips, is the industry's most acquisitive buyer. Intel announced 25 semiconductor deals over the past decade, with an average disclosed value of $1.65 billion.

Smaller transactions centered around acquiring specific talent and capabilities are becoming the industry norm, said John Ciacchella, principal TMT analyst at Deloitte Consulting.

"You're going to continue to see more interesting activity around those small deals," Ciacchella said. "It's been a constant in the industry."

Strategic partnerships

With large deals becoming more difficult, some companies are developing partnerships to tackle common challenges.

Qualcomm and Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. in July agreed to extend their patent license agreement for a range of mobile technologies, including 5G and 6G broadband cellular networks. The partnership will enable Samsung Galaxy products to operate with Qualcomm's Snapdragon processors for a variety of applications, including smartphones, computers, tablets and extended reality devices.

Separately, Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger and Samsung Vice Chairman Lee Jae-yong met in May to discuss how the two companies can work together to mitigate supply chain problems.

"There is pressure from both of their governments to cooperate," said Kagan's Paxton. "There's probably, arguably a better path forward for cooperation there, rather than just strictly competition."

Representatives from Intel and Samsung declined to comment on any potential partnerships between the two companies.

Companies outside of the semiconductor industry are also looking for ways to increase chip production. Last year, Dutch automaker Stellantis NV partnered with Foxconn to design and sell next-generation chips for the automobile industry.

"That kind of long-term partnership arrangement is something that we're going to see more of," said Clifford Chance's Grey. "It's not classic M&A, but it might give people more flexibility."

451 Research is part of S&P Global Market Intelligence.