Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

3 Mar, 2022

By Sanne Wass

| Russian sanctions are an "operational nightmare" for foreign banks and will likely result in them avoiding even permitted activity in Russia. |

International sanctions against Russia have sparked "overcompliance" and de-risking among foreign banks, which may impact cross-border payments and trade finance far beyond what governments had intended.

Sanctions come with exemptions that allow countries to pay for energy from Russia, yet the complexity of the rules and potential risks associated with any breaches mean it will be increasingly difficult to find a European or U.S. bank willing to facilitate even permissible trade with the country, according to experts. They say there is a real prospect of ending up in a situation similar to Iran, where banks continue to exercise excessive caution years after EU sanctions were lifted.

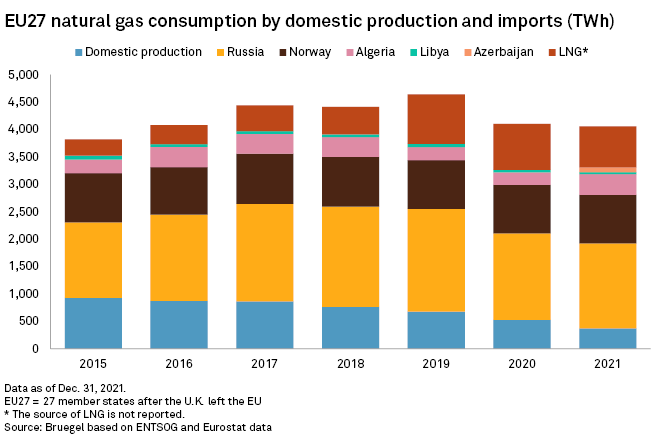

A lack of payment routes with Russia could become a challenge for the EU in particular, which relies on Russian supplies for close to 40% of its gas consumption.

"Everyone is closely scrutinizing the Russian-related activity, even the permissible activity," said Daniel Tannebaum, global head of sanctions at consulting firm Oliver Wyman. Many banks have already suspended any new Russian business as they are essentially "self-sanctioning" by proactively abandoning the market, he said.

Société Générale SA and Credit Suisse AG have halted the financing of commodities trading from Russia because of concerns that future sanctions could include energy, Bloomberg News reported Feb. 27. ING Groep NV said March 2 it would not do any new business with any Russian companies.

The rapidly changing sanctions and lack of uniformity between the specific regimes of U.S., U.K. and EU are posing particular challenges for banks, said Tannebaum. "We're getting to the point where it's just going to be too difficult. And I think that's where some banks may just decide to pull out," he said.

Financial institutions generally "put their own spin or policies over the top of the law" and will likely take a more conservative approach than what sanctions require of them, said Ross Denton, head of international trade at law firm Ashurst.

"Russia is too hot to handle at the moment, even though the law doesn't necessarily make it that way," said Denton.

The new sanctions are an "operational nightmare" for banks, according to Simon Taylor, co-founder of financial technology consultancy 11:FS. Lenders deal with future-dated contracts for oil, making it difficult to administer sanctions, and they will also face challenges in understanding which entities are sanctioned amid complex company hierarchies and a sanctions list that is growing daily. As such, banks will likely seek to de-risk as much as possible, he said.

Of the world's largest trade finance banks, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc., Deutsche Bank AG and HSBC Holdings PLC declined to comment on how sanctions are impacting their appetite for permissible Russian trade, though HSBC said it has little direct exposure to Russia. Standard Chartered PLC and BNP Paribas SA did not respond to requests for comment.

Some transactions go free

The U.S. has sanctioned Russia's two largest banks, VTB Bank PJSC and Sberbank of Russia, over Russia's military operations in Ukraine but has made broad exemptions on payments for purchases of crude oil, natural gas, fuel and other petroleum products in order to allow energy payments to continue and secure global supplies.

The EU has added institutions including Bank Rossiya, Promsvyazbank PJSC and VEB.RF to its sanctions list and banned seven Russian lenders from Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, or Swift, a messaging system that banks use to conduct cross-border payments and trade finance. However, the EU sanctions program and Swift ban do not apply to Sberbank and Gazprombank, Russia's largest and third-largest banks, which are key channels for payments for Russian oil and gas.

"What the EU intends is that some banks will not be sanctioned and/or there will be general or special licenses and that there will be banks willing to make payments," said Nigel Kushner, chief executive of law firm W Legal. "But I'm not convinced that will be easy to achieve."

Unless multiple governments provide significant comfort and pressurize a particular bank to process Russian payments, "they will not be willingly processed," Kushner said.

Breaching sanctions is a serious offense for a bank and has led to record penalties in the past. French bank BNP Paribas was fined $8.9 billion in 2015 after admitting to violating U.S. sanctions against Sudan, Iran and Cuba.

"In my experience, the moment some Russian banks are sanctioned, and the moment you have two, three or more sets of sanctions regimes which are similar but different, the reaction of, at the very least, the Western European and American banking system will be, 'we will not touch Russian banks full stop, and we will not touch Russian trade full stop,'" Kushner said. This is what happened with Iran and is now beginning to repeat itself with Russia, he said.

U.S. and European banks had by the early 2010s cut all ties with Iran in light of sanctions and exclusion of Iranian financial institutions from Swift. Most EU sanctions on Iran were lifted in 2016, but it is still impossible to find a European bank willing to process even legitimate payments to and from the country, said Kushner.

Political leaders in 2016, including then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond, sought to encourage nervous European banks to resume ties with Iran, but lenders have resisted doing business with the country for fear of falling foul of U.S. sanctions still in place.

An Iran-like situation is "exactly where we're headed," said Adam Tooze, historian and professor at Columbia University, although the Russian conflict is "much more delicate" because Russia is engaged in an actual invasion, which was not the case with Iran, he said.

Outside the banking world, companies are also lining up to exit Russia. Brands including Apple, Nike and Google have limited their services in the country, while shipping firms Maersk, MSC and CMA CGM have suspended non-essential deliveries to and from Russia.

The current level of "overcompliance" among banks and companies is unprecedented, said Maria Shagina, a visiting senior fellow at Finnish Institute of International Affairs.

"The chilling effect goes beyond everyone's expectations," Shagina said. "The banks and companies just don't want to touch anything that has to do with Russia because it's perceived toxic."