Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

20 Apr, 2021

| Box cores are used to evaluate polymetallic nodule resources containing valuable metals in the deep sea that are increasingly in demand to create batteries needed for the global energy transition. Source: DeepGreen Metals Inc. |

The world is moving closer to mining the deep sea to accommodate surging demand for battery metals needed in the global energy transition, but opposition to the practice is mounting.

After years of review, the International Seabed Authority, or ISA, is close to completing the exploitation regulations that would allow entities to begin collecting lumps of metal from the deep ocean. While some tout the process as a greener alternative to terrestrial mining, several ocean scientists and environmental groups are urging caution due to potential and unknown environmental consequences.

Polymetallic nodules are one of the top materials that mining and metals companies want from the deep sea. These nodules range in size up to about 20 centimeters and contain a mix of valuable metals including cobalt, nickel, copper and manganese. Strewn about the ocean floor at varying densities, they are abundant in a Pacific Ocean region between Mexico and Hawaii known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

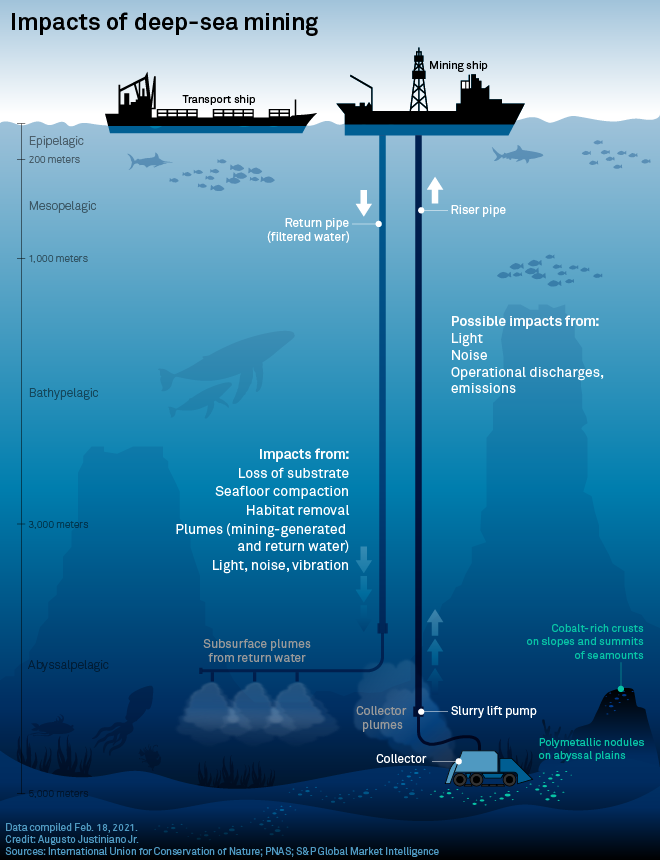

The mining process essentially entails scooping unattached polymetallic nodules off the seafloor, piping them to a ship at the surface and refining them.

"Mining nodules is more like harvesting potatoes than strip-mining or open-pit operations for ores in the earth," the ISA said on its website.

Demand for the deep-sea materials is likely to boom due to a worldwide thirst for batteries. The World Bank Group recently estimated the production of some minerals such as graphite, lithium and cobalt could increase by nearly 500% by 2050 to meet the growing need for clean energy technologies.

Electric vehicle sales across Germany, France, the U.K. and Norway increased 75% year over year in February, according to recent metals and mining research from S&P Global Market Intelligence. In China, the world's biggest EV market, plug-in EV sales are forecast to hit 1.9 million units this year and climb to over 5 million units in 2025.

Conventional mining and metals companies face increased scrutiny from investors and the public on environmental, social and governance principles. Geopolitical risks related to securing the metals needed for the energy transition are also increasingly drawing attention.

No longer science fiction

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, opened for signature in 1982, designated the deep sea and its resources as the "common heritage of humankind." According to the ISA, people discovered polymetallic nodules as far back as 1868 and have known since the explorations of the HMS Challenger in the 1870s that the nodules exist in oceans around the world.

Now, people are refining a process for exploiting those resources economically just as demand is rising and some are questioning the availability of traditional supplies.

"Many people ... think of [deep-sea mining] as science fiction," said Douglas McCauley, a professor of ocean science at the University of California, Santa Barbara. "But now it's actually science. It's actually an industry that is moving forward. In fact, it is sprinting forward."

The ISA, with 167 states and the EU among its membership, issued regulations on prospecting and exploring polymetallic nodules in the international seabed area in 2000. It has since started working on exploitation regulations that would enable the commercial collection of the nodules. The ISA had expected to complete that process in 2020, but the COVID-19 pandemic pushed the work into 2021. The U.S. is not a member of the ISA.

Critics of the ISA, including Greenpeace, have accused the agency of too frequently deferring to the interests of private companies pushing to exploit the resources. While the ISA touts its highest priority as protecting the ocean, Matthew Gianni, co-founder of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, said the body favors developing the resources over preserving the ocean.

"There's a bureaucratic momentum to mine," Gianni said. "The ISA is actually structured to hand out licenses rather than to rein in the process."

Aims to start mining by 2024

In March, Vancouver, British Columbia-based seabed mining company DeepGreen Metals Inc. announced it would go public through a $2.9 billion deal with ESG-focused blank-check company Sustainable Opportunities Acquisition Corp. to form an entity named TMC the metals company Inc., which will be operated as The Metals Co. DeepGreen is one of the most prominent voices in the ocean mining space and has said it hopes to begin commercial mining of the deep sea by 2024. The company has partnered with larger companies including Glencore PLC.

|

DeepGreen Metals Inc. CEO Gerard Barron addresses International Seabed Authority Annual Session in Kingston, Jamaica, in February 2019. |

DeepGreen CEO Gerard Barron told Market Intelligence the company is expecting the ISA to complete the final rules for exploiting polymetallic nodules by the end of the year and could adopt the rules when the body is able to reconvene.

"The externalities from fossil fuels are now very well understood," Barron said. "We haven't given the same attention to the onshore mining practices. When you look into them, it's not all that pretty. We can produce those metals and massively compress the ESG impacts."

Lockheed Martin Corp., the aerospace, arms, defense and security company, is also exploring ocean mining through its Uk Seabed Resources Ltd. subsidiary. The ISA has entered into 15-year contracts with 21 contractors to explore polymetallic nodules and other deep-seabed resources. Of the 21 contracts, 18 are looking for polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, according to the ISA's website.

Pushback from environmentalists, metals consumers

Prominent voices and companies have spoken out against ocean mining. Most recently, BMW Group, AB Volvo (publ), Samsung SDI Co. Ltd. and Google LLC announced they would commit to not source materials mined from the deep ocean. McCauley said the move aligned the companies with over 90 nongovernmental organizations and environmental leaders such as English broadcaster David Attenborough expressing concern about mining the ocean.

The health of the ocean is important to the Earth's larger ecosystem for several reasons, McCauley said. "There are some real potential alarming connections between ocean mining and ocean health and ocean ecosystems."

The researcher said that includes disrupting the ocean's role in sequestering greenhouse gasses. It could also could damage unique species, such as deep-sea coral as old as the pyramids or a recently discovered octopus species that lays its eggs on the minerals companies are trying to mine.

McCauley said the plumes of sediment generated by mining and processing activities could also disrupt the ecosystem in ways scientists do not yet fully understand. The plumes could be as large as 10 to 100 kilometers, last for weeks, and have a "smothering impact on biodiversity," McCauley warned.

| Warwick Miller, lead geologist with DeepGreen, holds a polymetallic nodule from a newly surfaced box core during a recent environmental research campaign. Source: DeepGreen Metals Inc. |

Jeffrey Drazen, a professor who studies the ocean at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, also described various environmental risks associated with deep-sea mining.

"We know a lot about the oceans quite generally," Drazen said. "But if you start to descend into the depths, our knowledge starts to fade away very rapidly."

Drazen pointed to one instance of scientists dragging small-scale farm plows and tracks across the ocean floor to simulate mining activity. When scientists returned to the site over 25 years later, there were still tracks on the seafloor, indicating the ecosystems there may be slow to bounce back from disturbance.

"These systems may not recover for well over a hundred or hundreds of years," Drazen said.

Ocean scientists and environmental groups have also pointed to potential harms to human food supplies and livelihoods supported by the fishing industry. The activities could also create indirect impacts from light, noise and sediment pollution.

The World Wildlife Federation recently called for the world to explore alternatives to deep-sea minerals with a focus on reducing overall demand for primary metals. They suggested transitioning to a closed-loop materials economy based on recycling and responsible development of terrestrial mining. In the meantime, the "planet's final frontier" should be left undisturbed, the group said.

Company defends environmental credentials

Barron said his company continues to build on decades of research on ocean life and ecosystems, including science-focused expeditions to understand the areas it hopes to mine. Those suggesting not enough is known to begin mining are "simply wrong," Barron said.

|

A nodule collected during DeepGreen Metals Inc's resource evaluation campaign in the Pacific Ocean's Clarion Clipperton Zone in September 2019. |

"There's no perfect solution to this problem around climate," Barron said. "What we believe, and what the science is proving, is that we can collect these nodules and turn them into battery metals and massively compress those ESG impacts."

DeepGreen commissioned a peer-reviewed study, published in the Journal of Cleaner Production, that examined climate change, biodiversity, social and economic impact factors from collecting nodules from the seafloor. The study concluded that making EV batteries from the nodules provides numerous advantages compared to using land-based ores, with the caveat that "further environmental-impact-assessment work is required to baseline and evaluate the impact of nodule collection on seabed wildlife and ecosystem function."

The company also intends to start with an end date for mining as the world transitions to recycling metals instead of mining them.

Drazen, who said he has contracted with DeepGreen to participate in a baseline study of the water column, said it would take a lot of research to appreciate the full risks of mining in the ocean but noted that there are ways to engineer solutions that minimize impacts. However, Drazen said monitoring the potential damage could be tremendously challenging due to the isolated nature of deep-sea mining.

"I don't get the impression that the public really understands what may begin occurring in the deep sea," Drazen said. "If we're going to have activities that are potentially so massive across the surface of the earth, I think the public needs to be informed. And not just a small group of people meeting in Jamaica at the ISA meetings."

Episodes of "Energy Evolution" are available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and other platforms.