Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

2 Mar, 2021

Three stray dogs with bright green fur polluted with an unknown toxic substance in Podolsk, about 22 miles from the center of Moscow, on Feb. 18.

Three stray dogs with bright green fur polluted with an unknown toxic substance in Podolsk, about 22 miles from the center of Moscow, on Feb. 18.

ESG has a new fan. The early weeks of 2021 have seen the Russian banking sector show love for the ethical investment philosophy that is slowly transforming the global financial sector.

In late January, Russia's largest bank, Sberbank of Russia, signed up to the United Nations' principles for responsible banking. The announcement coincided with the completion of a $300 million social eurobond issuance by PJSC Sovcombank, Russia's first signatory to the UN initiative in 2019.

Days later, the Association of Banks of Russia announced that it had approved recommendations for the implementation of environmental, social and governance principles by local lenders. And in the most recent nod to the advance of ESG, Central Bank of Russia Governor Elvira Nabiullina highlighted its importance, stressing that it constitutes a serious challenge for the Russian economy, its financial system and the regulator itself, which is working on rules for verifying ESG financial instruments.

That challenge comes primarily from the nature of Russia's largest industries.

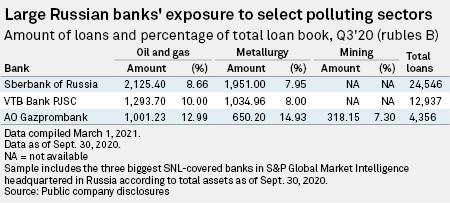

"The situation on the environmental side is difficult," Andrey Klapko, executive director, equity and financial institution banking research at Gazprombank, said in an interview. "The loan-book breakdown of the biggest Russian banks is heavily dependent on the structure of the Russian economy, which is heavily skewed towards dirty industries — and banks have to have an exposure to these dirty industries."

Key sectors

The oil and gas and metals and mining sectors make crucial contributions to the Russian economy. Fuel exports made up 42.1% of Russia's total exports of more than $336 billion in 2019, while iron, steel, gems and precious metals constituted another 9%.

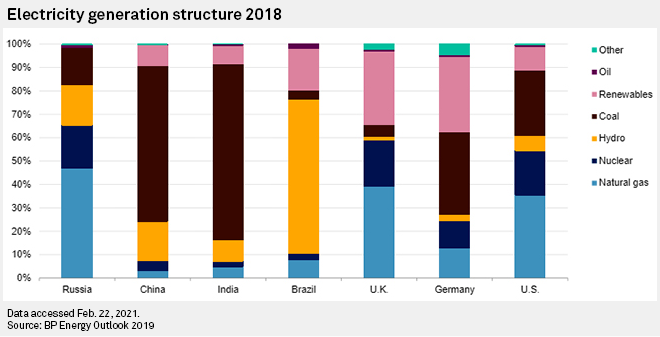

These industries are also large contributors to Russia's carbon footprint and its patchy record on controlling pollution. Russia was the world's fourth-worst CO2 emitter in 2018, the most recent year for which data is available. The country accounted for 5% of the world's CO2 emissions, behind China at 28%, the U.S. at 15% and India at 7%, according to data collated by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

While the Russian government's attitude toward climate change and environmental issues is shifting — the country finally ratified the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change in 2019 — pollution continues to increase in some areas. A study by consulting firm Finexpertiza based on data from Russia's Hydrometeorology Center found three times as many "high" and "extremely high" air pollution instances in the first nine months of 2020 than in all of 2019. The 171 instances of pollution in the nine-month period was higher than any annual total since records began in 2005.

Russian industry's record on environmental issues poses a particularly uncomfortable problem for the country's banks as ESG becomes increasingly hard to ignore. Some of the world's largest asset managers, as well as local Russian players, are taking progressively firmer stances on ESG when making investment decisions. If Russian banks, some of which are already operating under international sanctions imposed by the U.S., EU and U.K., want to avoid further restricting their access to capital, they must adapt to these demands, said Klapko.

Still, the central role many of Russia's most polluting industries and companies play in its society, and the swathe of communities built around them, means that a delicate approach must be taken by Russia's lenders to prevent damaging the country's social fabric.

About 9% of Sberbank's loans are to the oil and gas industry. For VTB Bank PJSC the figure is 10% and for AO Gazprombank 13%.

Dmitry Gusev, CEO of Sovcombank, which has been a frontrunner in the Russian banking sector's embrace of ESG, said its approach aims to strike the right balance between maintaining stable shareholder returns, providing decent living conditions for its employees, ensuring high-quality services for its customers and making a difference for wider society.

"The bank is not planning to change our lending policy overnight, and we have no plans to finance green projects exclusively," Gusev said.

"We are open to providing funding to challenging industries," he added, "provided they outline in their development strategy their goals and processes to reduce that negative impact. For companies not focused on reversing their negative environmental impacts, we will gradually reduce the amount of funding."

Leader of the pack

Much of the Russian banking sector's ultimate effectiveness in promoting ESG in the wider Russian economy will be determined by the role of Sberbank, by far the country's largest lender. Sberbank accounted for 36.1% of all lending to Russia's largest businesses and 29.9% of all lending to large and medium businesses in 2019, according to market and consumer data specialist Statista.

Based on Sberbank's presentation of its new strategy in December 2020, the Russian banking giant appears committed to making a positive impact through ESG lending, said Ekaterina Marushkevich, banking and insurance analyst at S&P Global Ratings. "Sberbank is very serious in its intentions to improve things," she said, highlighting that Sberbank identified ESG as one of three major areas of focus over the next three years. "At the top level of management at Sberbank, there is very good awareness of long-term ESG risks."

Still, as with Sovcombank, its approach will have to be delicately managed, Marushkevich added.

"What will constrain them is their exposure to environmental risks," she said. "They will not be able to stop lending to the largest Russian enterprises because of their social importance in various regions and cities."

Sberbank's influence on the Russian banking sector should convince those banks yet to fully commit to ESG that it is not just a fad that can be ignored, said Marushkevich. Currently, 7% of Russian banks already apply ESG principles in their business models, while 67% are preparing for the transition to ESG banking, according to an analysis carried out by the Association of the Banks of Russia.

"If we look back several years ago, ESG was perceived with a great portion of skepticism [in Russia]," said Marushkevich. "But recently we have seen more and more enthusiasm among our rated clients."

How much of that enthusiasm is born of goodwill and a sense of duty is debatable. As Gusev told Euromoney in a 2019 interview about Sovcombank's ESG efforts: "We are no altruists. We believe this is profitable."

For the larger, publicly listed banks in Russia, the nature of their motivations around ESG are unlikely to be too dissimilar, said Klapko. "There is a clear motivation for the public banks to tap the ESG investment money because the ESG agenda offers future opportunities for their market cap and valuation," he said.

"This agenda is shifting the landscape on the asset management side quite a bit."