Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

1 Feb, 2022

By Kip Keen

|

|

Fossil fuel-powered trucks at Canadian mines will become more expensive to run with a new clean fuel standard. |

A new Canadian clean fuel standard set to come into force in December 2022 could hurt Canada's mining competitiveness and divert investments in the sector.

A key industry concern is that, unlike Canada's carbon tax system, the clean fuel standard does not include protections for industries that sell products internationally at prices they do not control. For carbon taxes in Canada, which are a blend of provincial and federal policies, there are typically provisions to lessen the burden on energy-intensive trade-exposed, or EITE, industries.

"We're going to lose production, which will get absorbed elsewhere, almost inevitably at a higher carbon intensity," Brendan Marshall, vice president of economic and northern affairs with the Mining Association of Canada, said in an interview.

The new fuel regulation is set to chop the carbon intensity of gasoline and diesel in Canada by about 13% by 2030 relative to 2016 levels, according to the Canadian government. It requires primary fuel suppliers, including producers and importers, to reduce carbon intensity by blending in biofuels, buying emissions credits, or other innovations in oil production and refining.

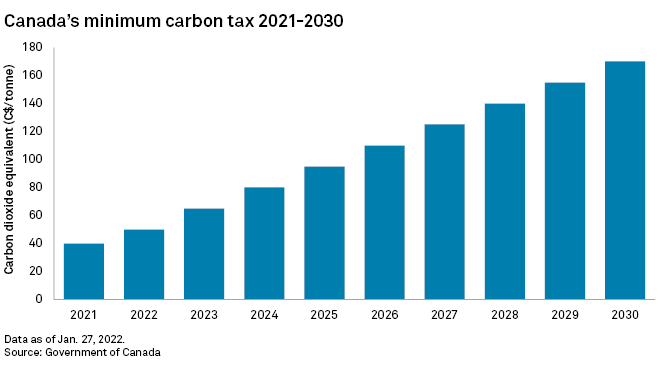

In part because of EITE provisions, the Mining Association of Canada has broadly supported the country's carbon tax system, which is among the world's most stringent. The minimum federal carbon tax is set to increase from $40 per tonne to $50/t of carbon dioxide equivalent on April 1 and increase $15/t per year until it reaches $170/t in 2030.

The EITE industry protections lessen carbon-tax pain for miners in many Canadian provinces and territories by setting a baseline for an industry's carbon intensity and exempting tax payment on a portion of emissions to help stem so-called carbon leakage from Canada's mining sector. Without them, the industry might close mines or avoid building new ones and instead invest in jurisdictions where weaker carbon emissions rules lead to lower production costs.

The clean fuel standard will add about $50/t in carbon equivalent costs, on top of the $170/t carbon tax by the start of the next decade, said Marshall, who hopes the federal government will make changes to the new rules before they are published. The final regulations are expected in spring.

A spokesperson for Canada's Minister of Environment and Climate Change Steven Guilbeault did not answer emailed questions about the potential impact of the clean fuel standard on the mining sector.

Dilution is no solution

But watering down the clean fuel standard to allay industry concerns over competitiveness would overly weaken the regulation's impact on Canada's carbon emissions and energy transition, said Bora Plumptre, a senior analyst with the Pembina Institute, a clean-energy think tank.

"There have been many exemptions and flexibilities already introduced to the policy, which have significantly undermined its original intent," Plumptre said in an interview. "If they further dilute the policy ... they're going to push the country further off course for the type of economic growth that we need to see in clean energies in the post-2030 period."

On the whole, Plumptre doubted the added cost of the regulations would put Canada at a huge disadvantage. Canada is middle of the pack in terms of global fuel costs, and the policy's impact on prices is relatively small compared to oil price volatility, Plumptre said, noting that by 2030 the fuel standard is expected to add 4 to 11 Canadian cents to gas prices and 4 to 13 Canadian cents to diesel prices.

"The high end there is really an upper bound representing a pretty unlikely scenario in terms of how compliance costs are expected to play out," the analyst said.

The higher Canadian carbon costs will be particularly hard on remote mines and projects where there are no economical alternatives to fossil fuels because sites are far from electric grid power, presenting a policy conundrum for Canada. The federal government has touted the country as well-positioned to develop energy transition industries, such as electric vehicle manufacturing, in part given its mineral wealth. However, its new decarbonization policy, without addressing international competition in the mining sector, could add costs and possibly imperil in-country mine development aimed at the very battery metals supporting the domestic EV supply chain.

In 2018, about 52% of Canada's nickel and 62% of its cobalt production came from off-grid mines, Marshall said, underscoring how Canada's battery metals are exposed to fossil fuel costs. Further, many Canadian mining projects are too far from grid power to make building extensions worth the capital cost.

"Until we achieve some type of technological revolution that allows the significant or total displacement of reliance on liquid fuels in a remote context, those prices are just increasingly going to be absorbed as a cost of doing business," Marshall said. Small modular nuclear reactors may one day be a solution for remote mines, Marshall noted, but are years away from being realistically deployed at Canadian projects.

Provincial disadvantage

Beyond the coming federal fuel standard, the issue of EITE industry policies is also rearing its head at the provincial level. Provinces in Canada can have their own carbon pricing regimes, including cap-and-trade systems, so long as they are in broad agreement with federal rules. Most provinces have EITE industry protections, but one exception is British Columbia, a major Canadian producer of base and precious metals and metallurgical coal.

The Western province sets its own carbon prices but without specific EITE industry protections, putting it at a competitive disadvantage, said Michael Goehring, president and CEO of the Mining Association of British Columbia. Goehring is "hopeful" the provincial government will address the issue, which has been raised through the province's Climate Solutions Council.

"If the status quo prevails, our industry is unanimous that opportunity will pass us by as investment shifts to jurisdictions with lower environmental and carbon protections and higher emissions," Goehring said. This includes investments going to other countries and regions of Canada where EITE industry regulations apply.

A provincial spokesperson did not respond to emailed questions about the impact of carbon policies on EITE industry.

As it stands, the cost difference can be significant for miners. For example, a mine emitting 100,000 tonnes a year of carbon dioxide would pay about C$300,000 in 2022 carbon taxes in metals-rich Ontario, Goehring said. But in British Columbia, the same hypothetical mine would pay between C$3 million and C$4 million. And at carbon prices set to hit $170/t in 2030, the operation would pay between C$15 million to C$17 million over emissions in British Columbia, Goehring said.