S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

28 May, 2021

By Declan Harty and Stefen Joshua Rasay

Silicon Valley wants Wall Street to make some room in the IPO market for the new generation of retail investors.

Retail investors have grown as a portion of U.S. stock trading, thanks to the coronavirus pandemic. Behind the two brokerages' IPO products is a question that has persisted across Wall Street and Washington for years: Should retail investors be able to invest in an IPO on day one at the opening price, just as BlackRock Inc., T. Rowe Price Group Inc. and other Wall Street giants have been able to for decades?

Wealthy individuals with at least $100,000 or so in assets can already buy into IPOs through some retail brokerages such as Fidelity Investments and The Charles Schwab Corp. Company insiders and their friends and families all have access to IPOs, with issuers commonly allocating shares for them through "directed share" programs. And some, like Airbnb Inc., have rewarded their customers and gig workers by allocating them shares. But wider access to the IPO market for individuals has remained limited, until now.

"Companies are realizing in the post-pandemic environment that retail investors can drive significant performance in their stock prices," Rosenblatt Securities Managing Director Vikas Shah said in an interview. "In a way, if the company has the right business model, you cannot have bigger cheerleaders than your own customers."

Both Robinhood and SoFi are partnering with investment banks to receive allocations of soon-to-be public stocks that their customers can purchase. SoFi has said it will help underwrite some offerings too, giving it more control over how to allocate the shares.

The first test of broader IPO access came May 27 with the New York Stock Exchange listing of FIGS Inc. The California-based healthcare clothing retailer said in its registration statement that it expected up to 1%, or a little more than 250,000 shares, of its IPO to be purchased by Robinhood customers. FIGS shares took off after opening for trading and ended their first day in the public market up 36.5% at $30.02.

With more than 13 million Robinhood customers at last count, the FIGS allocation was small. A maximum of only 2% of Robinhood's customers would have been able to buy a single share in the IPO, a fact that shows just how hard it could be for the brokerages to break open the IPO market for retail investors when investment bankers looking to satisfy their institutional clients remain in charge, said University of Florida finance professor Jay Ritter.

"The problem will always be, how can Robinhood get shares from some other underwriter when the underwriters want to give shares to their other clients?" Ritter said in an interview. "I don't see how Robinhood is going to solve that."

In the registration statement, FIGS wrote that the Robinhood allocation was done "at our request," signaling that issuers would need to initiate participation in Robinhood's product.

"Normally those opportunities are just for Wall Street insiders and other types of investors," FIGS co-founder and co-CEO Trina Spear said of IPO investing in a May 27 interview on CNBC. "So being able to provide this opportunity to our healthcare professionals was really important to us."

Anti-flipping

Expected to ramp up in the coming months, Robinhood and SoFi's IPO products are conceptually similar but do have differences.

SoFi, on the other hand, will require its members to have at least $3,000 in total account value with the brokerage to buy into an IPO. It plans to distribute IPO shares based on a customer's order size, total account value and past participation in its IPO product.

A spokesperson for Robinhood declined to comment for this story. SoFi, which is going public through a special purpose acquisition company merger, did not respond to a request for comment.

|

|

High risk, high reward

From options trading to using margin to buy more securities to now entering the IPO market, retail traders have more tools at their disposal than ever to make or lose money in the financial markets. But to some observers, like Barbara Roper, director of investor protection for the Consumer Federation of America, there are questions about whether any of those strategies are in fact suited for the small investors buying and selling securities through apps like Robinhood's and SoFi's.

"I know it's a lot glitzier and more exciting than having a good asset allocation plan, keeping your costs low and sticking with it," Roper said in an interview. "But [an IPO's] not anything a good financial adviser would recommend to the typical retail investor."

Anthony Noto, the CEO of SoFi and former executive with The Goldman Sachs Group Inc., seemed to address that concern in a March interview on CNBC when the company announced its IPO product, calling it "another step" in SoFi's work to provide its members with a way to build a diversified portfolio and invest over the long term. In addition to the company's flipping policy, SoFi may also charge a $50 fee to members who sell IPO shares within 120 days of the offering to discourage overeager trading.

"Obviously, initial public offerings are riskier assets than companies that have traded for a long time. So it's important that those positions that SoFi members take are a small portion of their overall portfolio," Noto said. "The retail channel is increasingly a really important channel as we've seen over the last several months. Having visibility into that retail channel will help those companies that are doing the IPOs better understand their shareholder base and make better decisions around pricing and allocation of shares."

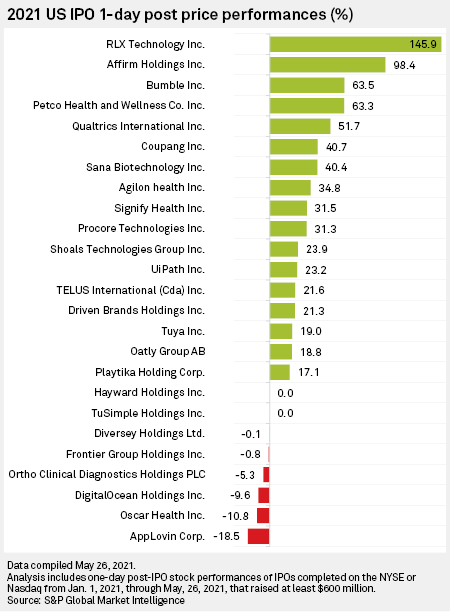

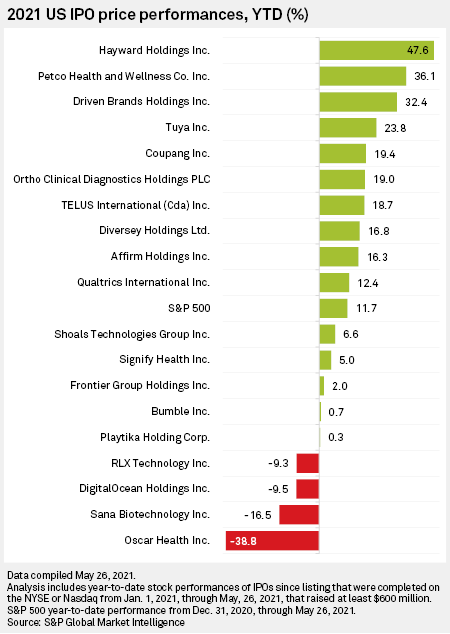

Corporate America and Wall Street have been working for years to provide individual investors with a way to tap into the IPO market, in part because of the share price jumps that issuers often see in their stock debuts. The 114 operating company IPOs in the U.S. so far in 2021 saw an average first-day return of 29.7%, according to data from the University of Florida's Ritter. Much of that bounce takes place in the stock's initial trades. But in some cases, IPO stocks that bounced on the first day can lose their shine in subsequent weeks or months. RLX Technology Inc., which had the best first-day performance of any U.S. IPO this year, raising at least $100 million, was trading 9.3% below its IPO price as of May 26.

Past attempts

In the past, issuers themselves have tried to solve the puzzle of getting retail investors more involved in IPOs.

One of the first to do so was Boston Beer Co. Inc. In 1995, the maker of Samuel Adams used its bottles to advertise $15 common shares in its upcoming IPO — a better deal than the $20 that Wall Street institutions were set to pay. About 30,000 people bought shares through the offer, according to a 1996 article from The New York Times, in which the company's founder estimated that about two-thirds of them were still holding their shares more than a year later. Boston Beer shares struggled for many years after the IPO. But anyone still holding their shares 25 years later would have booked a 6,770% gain as of May 27.

Not every retail investor-heavy IPO has gone well, though. In Vonage Holdings Corp.'s 2006 IPO, thousands of customers bought in through an expanded direct share program. But Vonage's stock plunged after opening at $17 per share, and it has not closed above that value in the 15 years since.

In a recent case, Deliveroo PLC partnered with Primarybid Ltd. to offer shares to customers in its March listing on the London Stock Exchange. About 70,000 of them bought shares at the £3.90 issue price, according to CNBC. Shares in Deliveroo tanked in their opening session March 31 and were trading at £3.59 May 24.

"If you're going to play in this world as retail, it's a bit of buyer-beware," a former New York Stock Exchange executive, who asked not to be named to respect business relationships, said in an interview.