Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

14 Apr, 2022

Former President Donald Trump broke ground at Foxconn's Wisconsin factory, which promised 13,000 jobs. The original $10 billion investment plan has been scaled back substantially.

U.S. companies have stepped up their exploration of reshoring supply chains after being caught out by dependence on Asia.

Companies including Intel Corp., General Motors Co. and U.S. Steel Corp. are building new manufacturing capacity in the U.S, while other executives have increased mentions of reshoring — bringing production back to their home countries — during investor calls since the COVID-19 crisis began. President Joe Biden has made moving supply chains closer to the U.S. a key pillar of his economic agenda, largely continuing efforts by his predecessors to rebuild domestic capacity and grow the number of high-paying manufacturing jobs.

"We're inundated with companies coming to us realizing that they need to reshore," Harry Moser, founder and president of Reshoring Initiative, said in an interview. The nonprofit organization looks to assist companies in bringing back manufacturing jobs to the U.S.

A tariff war, COVID-19 and now Russia's invasion of Ukraine have all strained once bullet-proof global supply chains, with delays and shortages hitting U.S. corporate revenues and helping drive inflation to its highest levels in decades. Wages are rising quickly in the U.S. as labor shortages and inflation push employees to demand higher compensation. Companies will respond by diversifying suppliers to other low-wage economies and increasing inventories rather than solely

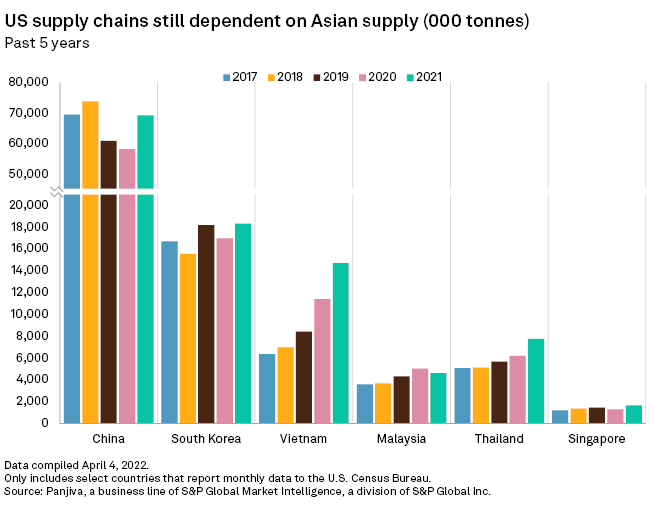

Talk of Asia's removal from supply chains should be taken "with a pinch of salt," said Rahul Kapoor, vice president at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

"At the margin, yes. That's driven by the cost of labor in China rising, driving away some of the low-cost products," Kapoor said in an interview. "But not all of that is moving back to the U.S. Vietnam is a big beneficiary, particularly after the Trump tariffs."

U.S. imports from across Asia grew in 2021, with China rebounding from a drop in exports the previous years and other Asian countries posting continued growth, according to Panjiva. Imports from Vietnam, for example, rose 28.9% year over year in 2021 and have more than doubled since 2017.

Highlighting a problem

The limitations of global supply chains were highlighted first by the political falling out between China and the U.S. and a raft of trade tariffs. COVID-19 brought lockdowns, closing factories and derailing shipping fleets.

"Pre-COVID the capacity at the ports, the trucking and shipping side, was able to take care of the bumps in the road that we saw, but it wasn't built for COVID-19," Kapoor said.

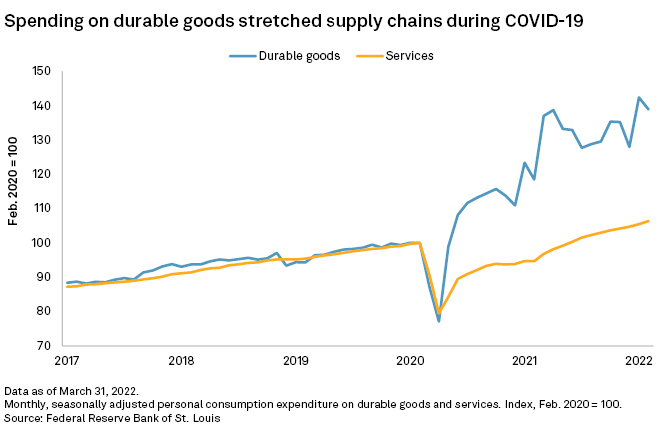

Supply chains were stretched by the recovery in demand of U.S. consumers, who were unable to spend on services like restaurants and cinema tickets because of COVID restrictions, but were able to buy goods.

"U.S. companies have taken multiple measures to address supply chain issues, including chartering freighters, rerouting shipping to smaller ports along the coasts, and relying more on air freight," said Lillian Lin, portfolio manager at PIMCO. Companies with more diversified supply chains, less concentrated in China, have done better than others.

The invasion "has put an end to the globalization we have experienced over the last three decades" Blackrock CEO Larry Fink said in a March letter to shareholders.

"While dependence on Russian energy is in the spotlight, companies and governments will also be looking more broadly at their dependencies on other nations," Fink wrote.

Disruption raises prospect of reshoring

Some companies are already making moves to bring supplies closer to home. Intel is investing $20 billion in two new plants in Arizona to boost domestic semiconductor supply. General Motors is moving its battery production to Michigan in a multibillion-dollar boost for the U.S. battery industry.

Other companies are making their plans known publicly. Most recently, executives with building materials supplier Martin Marietta Materials Inc., said during a February earnings call that they expect nonresidential construction to benefit from increased investment in reshoring of manufacturing to the United States.

|

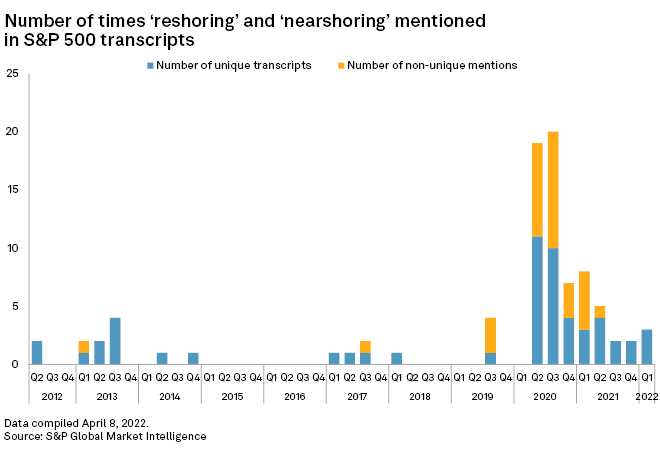

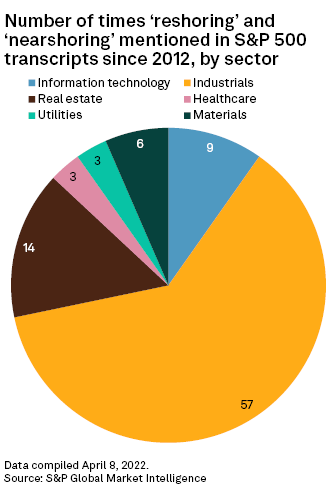

A study of transcripts of S&P 500 companies by S&P Global Market Intelligence found a spike in the number of mentions of reshoring supply chains during the last two years. Since 2012, executives with industrials companies have accounted for more than half of those mentions.

Reshoring and foreign direct investment contributed to nearly 262,000 jobs returning to the U.S. in 2021, up from nearly 179,000 a year earlier, according to data collected by Reshoring Initiative. A total of 1.3 million jobs have returned to the U.S. since 2010, with a further 3 million to 5 million jobs that could return if companies and governments embrace measures to support reshoring.

Companies are increasingly seeing the vulnerability and potential cost of being dependent on global supply chains, which can quickly break down, Reshoring Initiative's Moser said. Political tensions between the U.S. and China only grew during a trade war started by former President Donald Trump.

"We've had a surge in investment analysis firms coming to us and asking for our data because there will be an increasing opportunity for investment firms to ride the reshoring trend and invest in companies that will benefit the most," Moser said.

A November 2021 study by McKinsey found that 24% of sourcing executives at U.S. apparel companies include increasing reshoring in their strategies as well as nearshoring, away from Asia and toward Central America. A separate study in December 2021 by Goldman Sachs found that 75% of respondents plan to diversify their supply chains or increase inventories to protect themselves in the face of future shortages.

Still, some say that while the future may include certain high-end manufacturing coming home, relatively high wages in the U.S. mean that any reshoring will be at the margins.

"Reshoring is mostly a make-believe story told by politicians of both parties," Paul Ashworth, chief North America economist at Capital Economics, said in an email.

Ashworth pointed to the abandonment by Taiwan electronics manufacturer Foxconn Technology Co. Ltd. of a $10 billion investment in a Wisconsin plant. The scheme, designed to create 13,000 manufacturing jobs, had been hailed by then-President Trump as "the eighth wonder of the world."

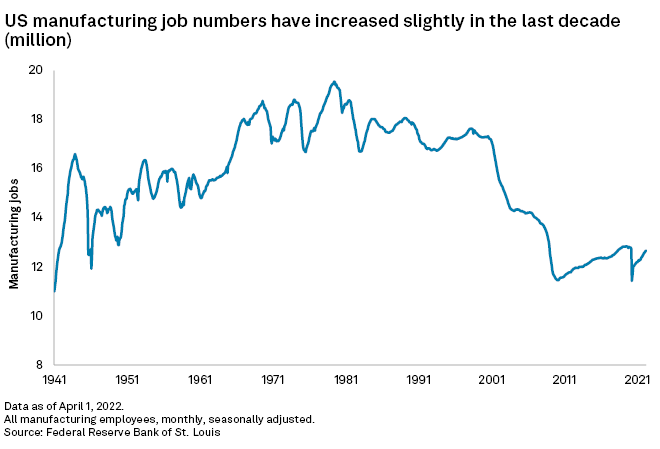

"The reality is that U.S. manufacturing employment is still below its pre-pandemic level and only two-thirds of what it was a couple of decades ago," Ashworth said.

Future dislocation

While the manufacturing reshoring after the tariff war "never amounted to much" the recent dislocation in supply chains has renewed focus on resilience, Goldman Sachs analysts said. It is possibly too soon to tell whether reshoring will be part of the answer to supply chain security rather than simply inventory restocking.

Not all production will return home, though there are limitations to relying on other Southeast Asian bloc countries, Moser said.

"That made sense for apparel or furniture, but if you want precision machining then Vietnam, Cambodia, etc., do not have the capability and skills. Depending on what the product is there are limitations to where you can go," Moser said.

The clearest problem facing proponents of U.S. reshoring is the cost of wages.

The cost disadvantages of bringing jobs back to the U.S. may worsen as wages rise at rapid rates. While the relatively high price of U.S. labor is the biggest drawback to bringing back jobs, technology can help make manufacturing more productive to reduce that cost, Moser said.

Yet with COVID-19 continuing to disrupt China, the conflict in Ukraine and the ice-cold diplomatic relations between the U.S. and China, the potential costs of further mass disruptions may persuade a growing number of companies that supply chains are safer at home.

"The disruptions, the tensions. That is a motivator that will cause companies to wake up and do the math," Moser said.

Panjiva is an offering of S&P Global Market Intelligence.