S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

3 Mar, 2021

Over the last couple months, several states and municipalities have introduced bills to study or implement public banks, potentially changing the financing landscape for large chunks of the country.

Most state-level public bank initiatives propose lenders that would use municipal deposits to fund projects within the state, such as infrastructure, agricultural production, economic development, low-income housing or environmental projects. Proponents say the public banks would ensure state money is used locally and reduce fee payments from municipalities

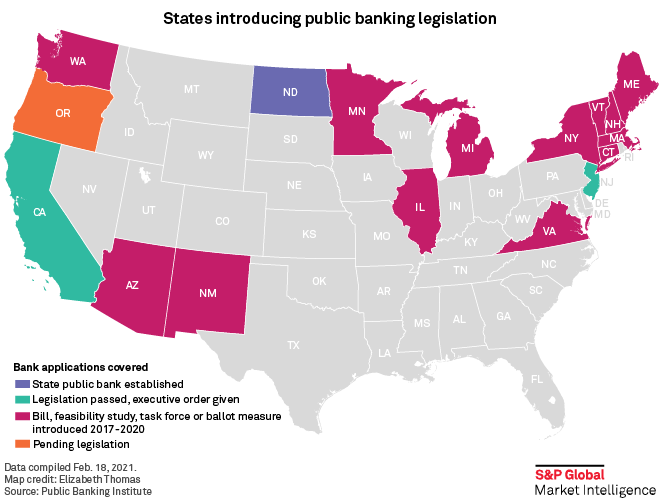

Oregon legislators on Jan. 11 introduced a bill that would launch a public bank. Washington officials on Jan. 13 introduced a bill to create a state bank. New Mexico lawmakers on Feb. 1 proposed legislation, in both the House and Senate, to open a state-level public bank. In Philadelphia, city officials on Jan. 28 proposed a public bank bill. Since 2017, several other states and municipalities have passed some type of public banking legislation, such as creating task forces to study the issue. And congressional leaders have raised the prospect at the federal level, including an infrastructure bank and a postal bank.

In California, lawmakers passed a bill in October 2019 that would allow municipalities to open their own banks, but so far no municipalities have applied for a bank charter. The City of San Francisco officials took a step toward that end last month when they issued an ordinance that establishes a working group focused on opening a public bank. In New Jersey, the governor signed an executive order in November 2019 to develop an implementation plan for a public bank, but news reports suggest the plans have been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Great Recession increased interest in public banking as communities felt "let down" by Wall Street banks and the number of community banks fell, said Angela Merkert, executive director of the Alliance for Local Economic Prosperity, an advocacy group for public banking in New Mexico.

The proposed bank in New Mexico would start with $50 million in capital from the state's investment fund and target small projects to benefit municipalities, Merkert said. Most municipalities in New Mexico only hold bond elections every two years, she said, so a public bank could enable quicker funding.

"If a county wants to upgrade its clinic facilities, in part due to what they've determined is so deeply lacking due to COVID, they could take out loans and get faster turnarounds on those renovations than waiting for the bonds to come through," Merkert said.

Public banks may also be a way for municipalities to earn more money on their deposits, said Walt McRee, chair emeritus of the Public Banking Institute, an advocacy group for public banking. "With a public bank, the state's resources will be better deployed and more productively used, and it can actually monetize its equity in a way that it can't do by borrowing from private capital markets," McRee said.

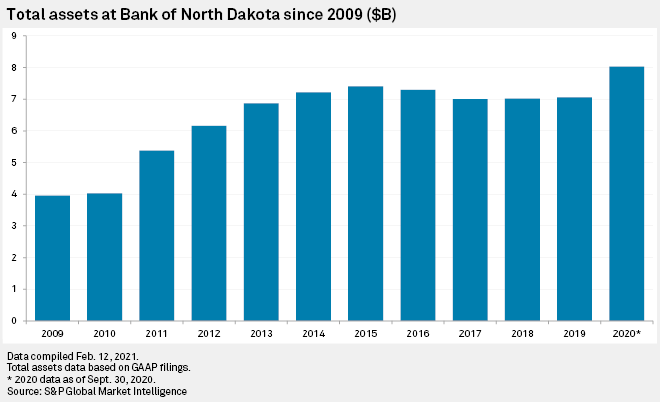

One state has operated a public bank for more than 100 years: Bank of North Dakota. In the third quarter of 2020, the most recent quarter for which the bank has filed data, Bank of North Dakota had a higher return on average assets and return on average equity than banks in the state, Midwest or the U.S. overall. The bank's efficiency ratio was only 16.79% at Sept. 30, 2020, compared to a median of 64.35% for U.S. banks.

As of Dec. 31, 2020, North Dakota had the highest number of banks and credit unions under $10 billion in total assets per capita in the country, which proponents of public banking say indicates public banks and community banks can co-exist and the presence of a public bank may even support community banking.

In North Dakota, the state bank partners with community banks to act as the state bank's "front office," McRee said. The bank administers its loans through local banks, creating an "ecosphere of collaborative credit," he said. The state bank also does not naturally compete much with private banks, McRee said, due to the types of higher-risk and longer-exposure loans the public bank often underwrites, which smaller banks are often unwilling to take on. Most of the bank's deposits come from the state's collection of taxes and fees. All state funds have to be deposited with the bank unless specific authority dictates otherwise, and the bank also takes deposits from corporate accounts, municipalities and residents.

"There's obviously some push to see it happen, but it just doesn't seem to me like it has the legs it really needs to get some backing for it," said Brett Rabatin, an equity analyst at Hovde Group who covers Umpqua Holdings Corp., the largest bank headquartered in Oregon.

Despite the fact that the California law has been in place for over a year, no municipalities have applied for a bank charter. Competition for municipal deposits and loans is already high, Rabatin said, creating a positive environment for cities and states.

"If you look at municipal deposits, they're very competitively bid," Rabatin said. "Banks would tell you that they would love to make more loans, but it's so competitive for them to not stretch on pricing, because of credit unions, because of nonbank competition."

Rabatin also questions the ability of public banks to avoid competing with community banks. The public bank would essentially create a closed market for deposits, leaving them unavailable to community banks and likely paying a lower rate to depositors than many banks. In order to be self-funding, the public bank would still need to charge interest on loans.

"It doesn't seem to me like there would be a big savings versus the open market," Rabatin said.