Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

9 Dec, 2021

By Alex Blackburne and Camilla Naschert

|

Wind turbines and electricity pylons in Runcorn, England. Cyber saboteurs are stepping up attacks on such power sector equipment. |

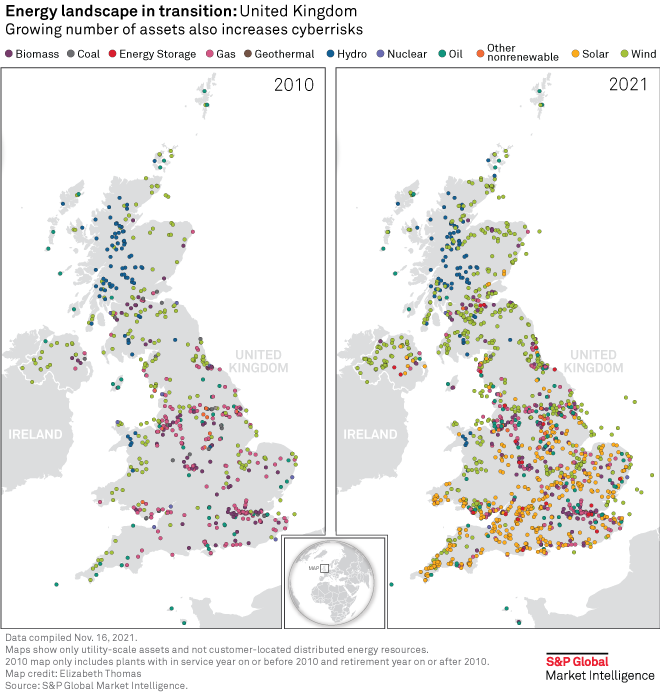

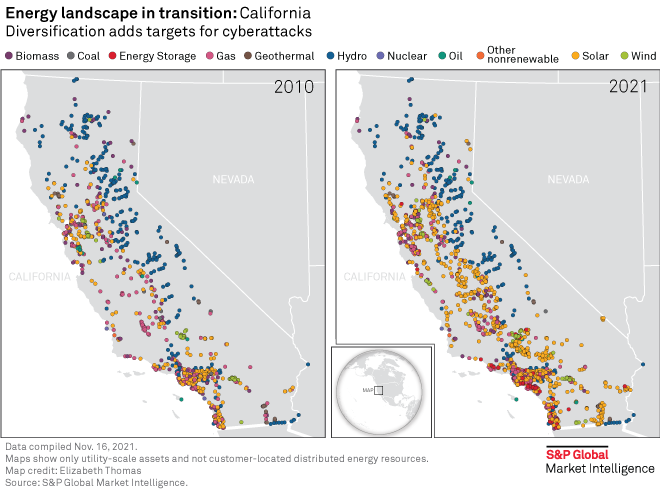

The electricity sector is grappling with an unintended consequence of the global energy transition: A greener, smarter and more interconnected power grid is also more vulnerable to cyberattacks.

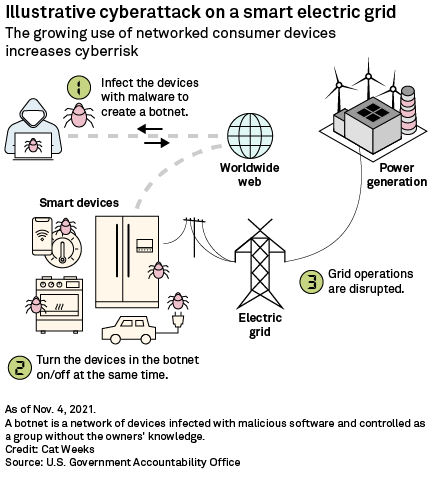

The influx of millions of smaller energy assets, from wind turbines and solar panels to electric vehicles and smart home devices, vastly increases potential entry points for hackers. Cybersecurity experts say it may only be a matter of time before major economies in Europe and the U.S., where decentralization is happening fastest, witness an incident like that in Ukraine in 2015, when cyber intruders successfully shut down part of the country's power grid.

|

Hackers have yet to compromise the system in North America, but "that doesn't mean it can't happen," Manny Cancel, senior vice president at the North American Electric Reliability Corp., said in an interview. "The adversaries absolutely possess the capability to do this."

With increasingly sophisticated attackers motivated by money, espionage or even terrorism, threats are mounting. So much so that 40% of executives across the energy and utilities industries now rank cyberattacks as their biggest risk, a figure higher than for any other area of the economy, according to a September survey by insurance group Beazley PLC.

"We are paranoid," Badri Kothandaraman, CEO of California-based power electronics supplier Enphase Energy Inc., said about the threat from cyber saboteurs. "And, in fact, we are thinking about it so much that we have integrated security into our product development strategy."

Citing hardware and software defenses, Kothandaraman said he is unaware of any breaches of Enphase products. That includes more than 38 million microinverters that serve as the electronic brains of more than 10,000 MW of solar capacity at homes and businesses, mostly in the U.S.

While digitalization and networked consumer devices are central facets of the energy transition, "that kind of data openness also has a flip side and creates exposure to people that want to misuse data," Kristian Ruby, secretary general of European utility trade body Eurelectric, said in an interview.

Risk of 'cascading effects'

There are likely millions of attempts to penetrate various corners of the power system every day. Cyberattacks were reported in November by Vestas Wind Systems A/S, the Danish wind-turbine maker, and Delta Montrose Electric Association, an electric utility in Colorado. In both cases, data and IT systems were compromised.

"Anything with a chip in it, or embedded software, is a potential vector for exploit," Cancel said.

At one wind farm in Germany operated by BayWa r.e. AG, a developer that manages more than 10 GW of renewables assets, its router recorded an attack attempt every eight seconds over an 84-hour period, according to Mohamed Harrou, the company's global head of supervisory control and data acquisition. Most attacks were automated, but some were done by humans.

In general, attacks do not have very complex origins; most start out as simple phishing attempts, Harrou said in an interview.

|

After entering a plant's network, hackers can sometimes sit inside for a year before making their move. From there, they could, in theory, manipulate a plant's data, change its settings and turn off security functions. Having access to multiple assets would allow intruders to orchestrate a larger-scale campaign, for instance altering the frequency of the plants in tandem to destabilize the grid and cause an outage.

"If you can get into many systems at the same time, you can ... create cascading effects," Anjos Nijk, managing director of the European Network for Cybersecurity, a nonprofit organization owned by European grid operators, said in an interview.

But gaining access to the network is one thing. In reality, intruders may need to jump through multiple hoops before they reach a level where blackouts are a real possibility.

"It takes a lot of resources, knowledge and experience," Samuel Linares, managing director and renewables security lead at consultancy Accenture PLC, said in an interview. "The power grid has a number of resilience measures."

However, cyber saboteurs are growing in sophistication and strength. The 2020 hack on software company SolarWinds Corp. — the largest cyberattack ever seen, according to Microsoft Corp., affecting 18,000 organizations — was reportedly the work of more than 1,000 developers.

The event illustrated that criminals, having learned to amplify their impact by infecting a widely used enterprise platform, ultimately could migrate to the operational technologies of energy delivery, according to Cancel. Hackers are persistent, stealthy, patient and "great at obfuscating," Cancel said.

American and European cybersecurity experts are most concerned about state-sponsored threats and organized crime syndicates linked to China and Russia. But the roster of agitators is much longer.

"Who is not?" Nijk said, referring to which nations are capable of cyberattacks.

Attackers also include independent "hacktivists" and disgruntled insiders, often using cyber intrusion as money-making exercises.

In one case, hackers gained control of a solar farm's closed-circuit television network and used it to mine cryptocurrency, according to Rafael Narezzi, chief technology officer at CF Partners (UK) LLP, a trading and asset management firm. "[They were] making money off someone else's devices that have ... electricity and memory," Narezzi said in an interview.

Addressing the threat

Safeguarding the grid means raising awareness of cybersecurity risks and implementing strong regulation across interconnected regions, power sector officials and cybersecurity experts said.

The EU Network and Information Security directive from 2016 formed the basis for national cross-sector legislation to be introduced by EU member states. In a reflection of the power grid's growing asset diversity, the directive is being updated to expand its scope beyond electricity generation and networks and into areas such as demand response, energy storage and hydrogen.

In the U.S., the Biden administration in April launched a 100-day action plan focused on industrial control systems. These systems, which were compromised in the Ukraine attack, are of particular concern because of the essential role they play in monitoring and directing the critical physical functions of generation, transmission and distribution.

In a March report to Congress, the U.S. Government Accountability Office flagged cyberrisks associated with industrial control systems and called for the U.S. Energy Department to redouble its efforts to better protect the distribution grid.

However, U.S. distribution grids are generally not subject to mandatory cybersecurity standards developed and enforced by NERC for high-voltage transmission systems.

Still, at least 150 U.S. electric utilities have adopted or committed to adopting detection, monitoring and other technologies to improve the defenses of their industrial control systems, the DOE said in an update on the 100-day initiative. The DOE also received input from vendors of cybersecurity solutions for industrial control systems — companies including Cisco Systems Inc., Microsoft Corp. and Siemens Energy AG — on how to manage threats to the grid through supply chain vulnerabilities.

Meanwhile, the DOE and its National Renewable Energy Laboratory in October partnered with utilities Xcel Energy Inc. and Berkshire Hathaway Energy to launch the Clean Energy Cybersecurity Accelerator. The initiative aims to support a transition to net-zero emissions by midcentury with new cybersecurity solutions. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory will vet the proposed approaches at a 20-MW laboratory designed to evaluate the protection of renewable energy systems.

But the lack of "really clear and robust cybersecurity standards" for distributed energy resources has been a stumbling block, according to Xavier Francia, an expert on the grid's cyberrisks at the Electric Power Research Institute, whose members span more than three dozen countries and include most of the largest utilities in the U.S.

"That's certainly a struggle everyone is dealing with — not just utilities, but device manufacturers, implementers of [distributed energy] systems," Francia said. The Electric Power Research Institute has a cybersecurity research project focused on microgrids, EVs, smart inverters and other distributed energy resources.

The efforts aims to address "a major trust problem" that utilities have when interfacing more with third-party market participants using the internet, the cybersecurity expert said.

Still, government and industry leaders in the U.S. and Canada are preparing for the worst. In November, NERC simulated a multifront barrage of cyber and physical assaults on the North American electricity system to test response and recovery strategies.

While the precise details of the exercise, known as GridEx, are confidential for security purposes, it was "designed to simulate the failure of the grid," said Cancel, who leads NERC's Electricity Information Sharing and Analysis Center, which hosts the event. The simulation explored grid security risks associated with other critical infrastructure industries, such as natural gas, as well as cross-sector mutual aid efforts, Cancel added.

|

A technician inspects inverters at a solar array in Oxford, Mass. |

Strategic silence

While information sharing on cybersecurity is important, power sector participants are generally tight-lipped in public about specific approaches, usually citing concerns over security. Out of more than two-dozen utilities, renewables operators and grid companies contacted by S&P Global Market Intelligence, only a few provided responses.

A spokesperson for Duke Energy Corp., one of the largest utilities in the U.S., stressed the company's "multilayered approach" and "proactive risks mitigation strategy."

Various media outlets reported in 2019 that Duke was the unnamed power company that was fined $10 million for 127 alleged violations of NERC's mandatory critical infrastructure protection standards. The utility declined to comment on the matter.

Norwegian utility Statkraft AS and German grid operator Amprion GmbH acknowledged the cybersecurity challenge but also offered little about their actual strategies.

A spokesperson for U.K. grid operator National Grid Electricity System Operator Ltd. said only that the company has "robust cybersecurity measures" in place across its entire IT and operational infrastructure that are reviewed regularly to ensure security of supply. National Grid Partners, the venture investment arm of National Grid PLC, is an investor in Dragos Inc., which provides cybersecurity solutions for industrial infrastructure.

Harrou outlined some techniques used at BayWa r.e. Its plants use whitelist firewalls, for instance, which allow network access only to certain authorized individuals, as opposed to the blacklisting approach that grants access by default but blocks suspicious entities.

"As easy as it is to hack a wind farm, it's as easy to protect it," Harrou said. "It's not rocket science."

And yet, the issue of cybersecurity remains high on the agenda in the power sector. That is partly because customers and investors are more frequently asking company bosses about it, Harrou said. But it is more fundamentally because of the massive surge in cyberrisk accompanying digitalization and decentralization.

"When we started in 2012, CEOs were looking at me saying, 'What are you talking about? It cannot happen,'" Nijk said. "This has really massively changed."