Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

4 Apr, 2022

By Lauren Seay

The banking industry is buzzing about the apparent addition of a single large institution to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.'s list of problem banks, and experts say a management issue is likely at fault.

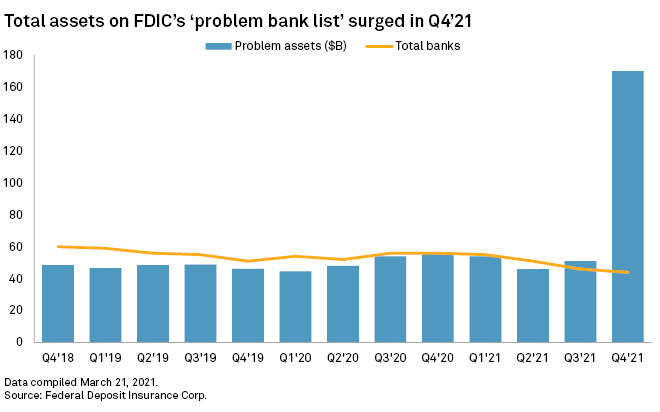

The number of institutions on the FDIC's problem bank list actually declined in the fourth quarter to 44, from 46 a quarter earlier. The total assets of institutions designated as problem banks, however, jumped by almost $120 billion, suggesting that one sizable institution was responsible for the increase. The FDIC does not disclose the identity of banks on the list.

The increase, disclosed in March, raised eyebrows in the banking and investment community, sparking questions over why an institution, in a benign operating environment, would meet the FDIC's definition of a problem bank. Under the FDIC's definition, a problem bank has "financial, operational or managerial weaknesses that threaten their continued financial viability."

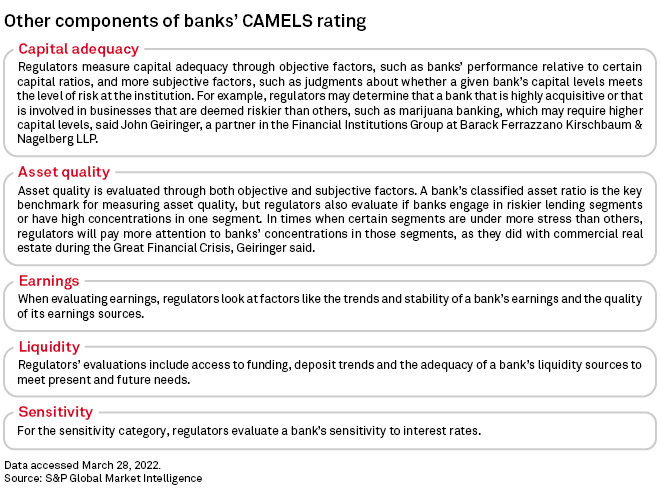

Banks land on the FDIC problem bank list based on multiple possible factors, as measured on the FDIC's so-called CAMELS scale, which measures a bank's capital adequacy, asset quality, management, earnings, liquidity and sensitivity on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the worst.

At a time when capital and liquidity levels are high, credit quality is near-pristine and earnings and sensitivity are largely non-factors, industry experts said a deterioration in the management category — which includes compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act, or BSA, and anti-money laundering, or AML, policies — was likely what landed one large bank on the list.

"Where we are at this time of the cycle means that management kind of tips the scale even more than it normally would," Christopher Marinac, an analyst with Janney Montgomery Scott, said in an interview.

Management ratings growing in importance

The management category is the most subjective part of the CAMELS rating, since it involves qualitative factors such as succession planning; risk management and procedures; and BSA/AML compliance, said John Geiringer, a partner in the Financial Institutions Group at Barack Ferrazzano Kirschbaum & Nagelberg LLP.

"Some of those things don't lend themselves easily to objective standards, but regulators look at the totality of circumstances to see whether or not banks are complying with applicable laws and whether or not they take seriously recommendations by their regulators," he said in an interview.

Over the past decade, the management rating has been gaining more traction as an important factor, as regulators view the factors within the rating as "just as big a risk to the safety and soundness of the bank as credit risk or your capital ratios," said Craig Nazzaro, a partner at Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough LLP.

Moreover, because financial metrics such as capital, asset quality, earnings and liquidity have all been relatively untroubled recently, regulators' concerns have generally centered instead around management-related factors such as BSA/AML compliance, risk management issues and riskier business models, including those involving marijuana or international trade, Geiringer said.

In the near future, current events could put an even larger emphasis on the management rating as inflation soars and the Russian invasion of Ukraine increases cybersecurity risk, industry experts said.

BSA/AML at the forefront of regulators' minds

Within the management category, anti-money laundering procedures and Bank Secrecy Act compliance have taken precedence in regulators' minds, Chip MacDonald, financial services lawyer at Jones Day, said in an interview.

"It's been a hot button for the last five to 10 years," MacDonald said. "But it's a real hot button now, because I think the regulators expect the industry to make more progress."

Regulators including the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, have become hyperaware of BSA/AML compliance over the past decade, as technology has allowed institutions to scale rapidly, sometimes faster than compliance controls are able to catch up, Nazzaro said.

"You can see it just from certain banks dipping their toes in newer waters," he said. "Either a new product set or greater sophistication on the technology side will lead to growth that is unmatched in their compliance controls, and I think the OCC, as well as the other regulators, are seeing that as a significant risk to the bank itself."

Typically only persistent BSA/AML compliance issues affect the management rating, Nazzaro said.

"If you grew very quickly or you just came out of a period of expansional growth, I think the regulators are fairly reasonable," he said. However, if an institution does not address compliance problems within their regulator's time frame, "that's what starts to more easily impact the CAMELS rating, rather than the initial violation," he added.

Any bank with long-standing BSA/AML compliance will have difficulty securing a management rating lower than 3, MacDonald said.

"If they're severe and long-running, and they're not getting better in the regulators' minds because management isn't doing enough, that's when you get civil money penalties, and you get cease and desist orders and the like," he said. "And that is going to take down your CAMELS rating, and it may take it down into the 4 to 5 range."

If a bank falls to a 4 or 5 CAMELS rating, landing it on the problem bank list, regulators typically impose public enforcement actions, laying out restrictions that can include controls on growth or required approvals for new senior officers or directors, Geiringer said.

"The lower you slide down, the more restrictions are placed on you," he said.