Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

26 Feb, 2021

While much of the U.S. investment community and many large corporations are moving to adopt sustainability-focused approaches and provide related disclosures, the deep political divide on that topic was on display at a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee hearing Feb. 25.

The House Financial Services Committee's Subcommittee on Investor Protection, Entrepreneurship and Capital Markets held a pre-mark-up hearing regarding a handful of bills that would mandate publicly traded companies disclose their climate and other environmental, social and governance risks.

The Democrat-controlled committee heard testimony from several panelists representing groups and pension fund managers pressing for such mandates. The Republican party's witness on the panel — a former CEO of a biotech company who is writing a book on the topic — claimed that disclosure mandates and the ESG movement more broadly threaten democracy by allowing rich investors and corporations to dictate what should be done on issues of morality and public policy. Notably absent from the witness list were any representatives of traditionally conservative trade groups that in prior years had testified about their concerns regarding the ESG movement.

Outside of the legislative process, President Joe Biden has pledged to make companies disclose their climate risks and emissions levels. And the acting head of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission on Feb. 24 announced that the agency has opened a review of public company climate disclosures and is looking to update the agency's 2010 guidance on that topic.

At the start of the hearing Thursday, Subcommittee Chairman Brad Sherman of California argued that climate change and other ESG issues are material to shareholders and will affect their financial performance. Moreover, "investors themselves are interested in these social issues," Sherman said. He said companies need to go beyond dedicating a page or two in their annual 10-K reports to ESG issues and instead provide in-depth standardized details that will adequately inform investors and the public.

But at the same time, Sherman said the disclosure requirements will need to be crafted carefully to not make companies disclose everything under the sun. "We can't turn Form 10-K into a telephone book," he said.

Republican Bill Huizenga of Michigan, ranking member of the subcommittee, acknowledged that investor demand for ESG data has increased, but he asserted that keeping disclosures voluntary is appropriate. The disclosures are being used to name and shame companies and to create corporate villains in the public eye, Huizenga said.

The SEC "must remain focused on protecting investors ... and facilitating capital formation," Huizenga said. He also argued that very little evidence exists to show that ESG investing results in better performance than major indices.

An S&P Global Market Intelligence analysis in August 2020 showed that several large ESG ETFs and mutual funds were outperforming the S&P 500 amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

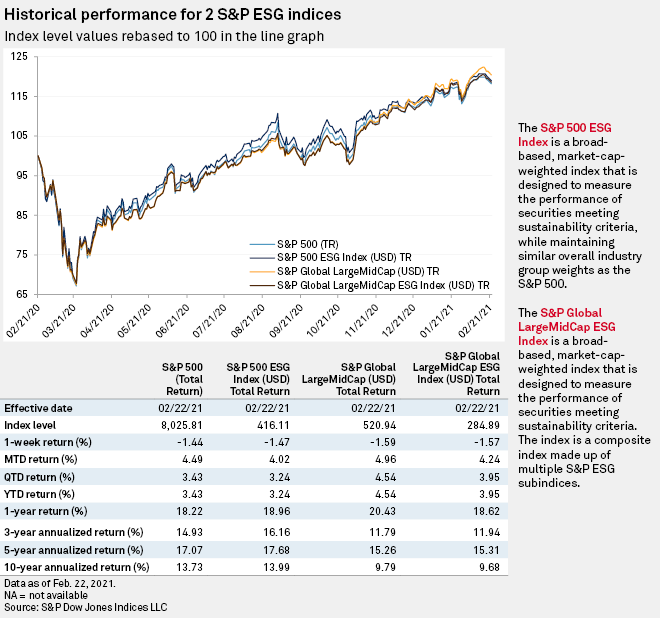

More recently, the one-year total return for the S&P 500 ESG index was slightly higher than the total return for the S&P 500, while the S&P Global LargeMidCap ESG index underperformed its benchmark over the same period. These two ESG indices outperformed their benchmarks on a three-year and five-year basis.

Companies are increasingly publishing ESG-related reports. According to the 2021 State of GreenBiz report published in conjunction with S&P Global Trucost, 90% of the 500 biggest U.S. public companies had a sustainability report in 2019, up 11% from 2015 levels.

While the amount of disclosures has grown, the quality has not improved, said Veena Ramani at Thursday's hearing. Ramani is Senior Program Director of Capital Market Systems at the sustainability-focused investor activist group Ceres. Ceres is the primary organizer behind the Climate Action 100+ initiative of investors pressing companies to assess, disclose and address climate risks.

The climate crisis poses a systemic risk to the health of companies and the broader economy, Ramani argued. And robust disclosure is key to helping corporations and others address those risks. "Climate change information doesn't just need to be good, it needs to be as good as possible," Ramani said.

Echoing Ramani's arguments, California Public Employees' Retirement System Investment Manager James Andrus testified that initiatives such as Climate Action 100+ "are poor substitutes for policy and regulatory action." CalPERS is the largest pension fund in the U.S., with approximately $432 billion in total fund market value as of December 2020.