Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

13 Dec, 2021

|

Even as many companies around the globe roll out net-zero climate pledges, the long-range nature of the goals leaves many questions about the exact path toward eliminating greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Large corporations' full carbon footprint is wide-ranging, and making and shipping a product is just one of many sources of emissions that could prove difficult to reduce. |

Corporations ramped up commitments to drive down their greenhouse gas emissions in the last year, offering the promise of trillions of dollars of green investments. Now, investors and activists are increasingly demanding transparency and action to back those pledges.

|

The recent climate talks at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, presented a sharp focus on the private financial sector's role in combatting climate change and the sector's potential cascading effects on other parts of the economy. Some companies said they cannot reach zero emissions, but many seek to shrink their carbon footprints while offsetting remaining emissions by investing in carbon reduction elsewhere in the economy. A company is considered to have achieved net-zero when its emissions are entirely offset by reductions that it pays for elsewhere.

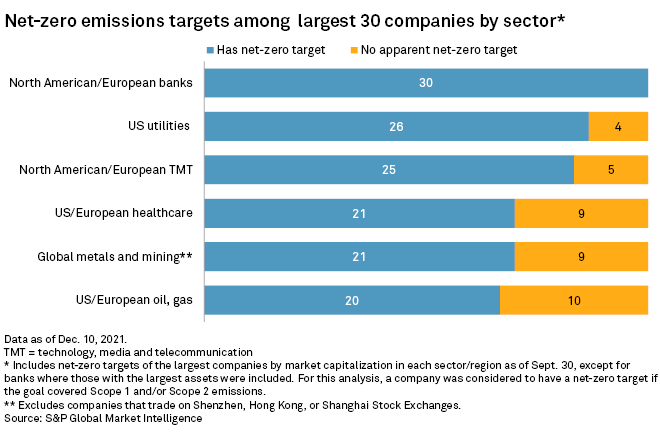

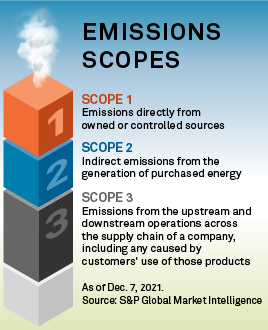

Of the 180 companies examined by S&P Global Market Intelligence across a variety of sectors and regions, 143, or 79.4%, have set some form of a net-zero target. The move to squeeze emissions is not limited to the private sector: On Dec. 8, U.S. President Joe Biden released an executive order calling on the federal government to reach net-zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050 across its Scope 1, Scope 2 and Scope 3 emissions.

Critics argued that corporate net-zero pledges are just window dressing, the latest way for polluters to avoid possibly painful adjustments to their operations. But advocates said that the vast resources the private sector can bring to bear on the climate change problem can be the impetus for reduction the world needs.

"Policymakers, investors and society are serious about trying to transition and trying to transition fast," said Jaakko Kooroshy, global head of sustainable investment research at FTSE Russell, a business of the London Stock Exchange Group. "We're going to see society becoming even pushier about it. So you need a plan, and you need to have the right level of ambition in that plan."

Accountability required

Assessing net-zero promises remains a challenge, as business sectors have substantially different emission profiles. For example, manufacturing facilities will produce far more direct emissions than the average financial institution. Financial institutions sometimes tout their low-carbon operations, while some lending portfolios — those not scrutinized through a climate lens — can funnel funds to emissions-dense operations that exacerbate global warming.

Investors weighing climate change in their decision-making are leading while governments are following, said Kirsten Spalding, senior program director for the Ceres Investor Network, a nonprofit that includes more than 200 institutional investors managing more than $47 trillion in assets. Those investors increasingly want to know the details of how a company will deal with all of its associated emissions.

"The investors are saying to companies, 'It's not enough even to give us the interim targets, you've got to show us how you're going to get there,'" Spalding said in an interview. "If you say you've got an interim target, but then you're not actually aligning your business practice with it, that's a problem."

Spalding said investors are also beginning to pay attention to companies that make net-zero pledges but quietly support industry associations that advocate against policies that would drive emissions reductions.

"Investors are now saying, 'If your policy work is going in one direction, and you claim to be achieving a target, really, this is not credible,'" Spalding said.

Other critics take a harder line. Net-zero is a "corrupted concept" that allows companies to put off earlier action in favor of long-range goals and to offset emissions rather than commit to absolute reductions, said Karen Orenstein, director of the climate and energy justice program at environmental organization Friends of the Earth.

"Net-zero has become the shiny smokescreen for delaying action to some later decade and pretending that you're doing something," Orenstein said. "It's totally become a greenwashing gimmick."

The complications in measuring compliance

A net-zero goal can mean many things coming from different companies, said Kyle Harrison, head of sustainability research at Bloomberg New Energy Finance. That makes it difficult for investors not highly familiar with a slew of acronyms and standards to assess net-zero targets.

|

A good net-zero goal, Harrison said, addresses a company's Scope 3 emissions — emissions as a result of activities from assets not owned or controlled by the company or organization but upstream or downstream of the company in the supply chain.

"If oil companies can set net-zero goals that include Scope 3 emissions, at least in terms of ambition, there are opportunities for all these other sectors to do it as well," Harrison said.

Other factors to watch for include interim targets that create accountability on the way to the ultimate goal and whether an organization sets its sights on hitting targets earlier than 2050. Interim goals and earlier target years increase the accountability for a management team that could be long gone once nearly three decades have passed.

"If you are an oil producer today or if you are a shipping company today or an airline today, and you're setting a net-zero target for 2050, what you're effectively saying is that you understand the challenge and that you are committed to navigating a challenge," Kooroshy said. "Part of that process over the coming decades will be really a transformation of the core technologies and the core business models that are at the heart of the company."

READ MORE

Theme

Segment