S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

8 Jun, 2022

By Dylan Thomas

The outlook for private equity dealmaking has soured since the start of the year as the industry grapples with rising inflation and interest rates, according to industry sources.

Do not expect transactions to grind to a halt as they did at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the second quarter of 2020 because deal flow tends to deaccelerate slowly, said Kelly DePonte, managing director and head of research at Probitas Partners LP. But a slowdown is taking hold as Russia's war in Ukraine, the pandemic and ongoing supply chain snags undermine confidence in the global economy.

"At the very least, the first five months of this year have put the fear of God into GPs," DePonte said. "The people who are doing deals now are really sharpening their pencils because there's downside risk."

KKR & Co. Inc. CFO Robert Lewin said on his firm's first-quarter earnings call that the economy was entering a "stickier inflation environment" and named three key forces driving inflation: wage growth resulting from tight labor markets, the U.S. housing shortage and a lack of investment in the energy infrastructure. Lewin predicted 2022 would see inflation in the range of 7% to 8%, with moderation coming in 2023.

If there is an upside to this uncertain moment, DePonte said, it is that spiking inflation and interest rates also drive down valuation multiples, making it a good time for private equity firms to add to their portfolios. But any buying opportunities private equity firms are scouting now might not solidify until the target companies come to terms with their new normal.

"There's just a lot of stuff moving through income statements right now that is tough to measure," explained Bob Bartell, president of Kroll Inc.'s corporate finance and investment banking practice. "What is true EBITDA and cash flow of a business? There's just a lot of stuff that is difficult to project because of higher interest rates, higher oil prices, higher food prices, all the commodities. If a company is using and reliant on copper and aluminum and other metals, their business is getting impacted."

Smaller deals, less risk

Bartell noted rising inflation also goes hand in hand with stricter underwriting standards, making it

"You will deploy less leverage at closing, which may push down returns. But then you have, in theory, less financial risk as well. Meaning you have a well-capitalized business and the investment opportunity can come from operational improvements, not just from straight financial engineering," he said.

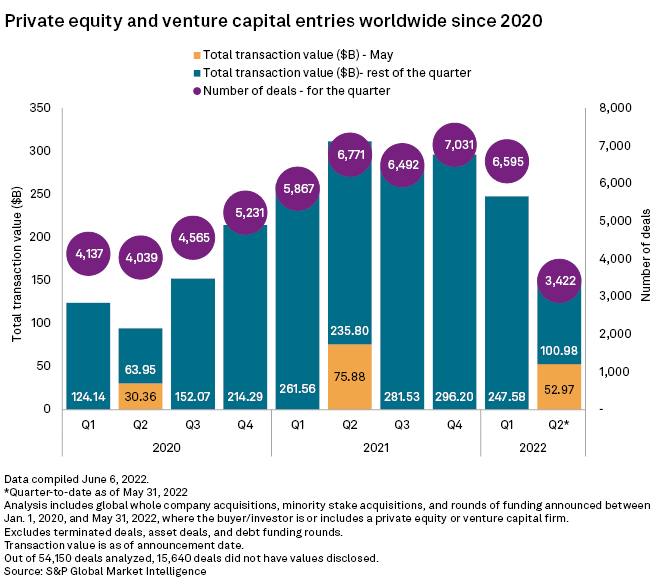

Global private equity and venture capital entries in May totaled $52.97 billion, a greater than 30% decline from the same month a year ago and the lowest aggregate value recorded in at least a year, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. The 1,652 deals for the month represented a nearly 18% decline in volume from May 2021.

With 10,017 deals recorded through the first five months of the year, entries to date are still pacing ahead of the previous four years, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. But at $401.53 billion, the total value of those deals is nearly 7% lower than the total recorded in the first five months of 2021.

A test for managers

Among the large publicly traded U.S. alternative asset managers, most reported single-digit appreciation for their private equity portfolios in the first quarter. Ares Management Corp. and KKR had said their private equity portfolios lost value, with the Ares' flagship corporate private equity posting gross returns of negative 1% for the quarter and KKR marking down its traditional private equity portfolio 5%.

Peppered with analyst questions about the impact of inflation and interest rates on their portfolios, executives largely emphasized the fundamental strength of their portfolio companies, focusing on the potential for steady growth businesses with strong cash flow to outrun inflation, as Blackstone Inc. President and COO Jonathan Gray put it.

But Bartell said those performance statistics from the first three months of the year probably do not capture the full impact of market rattling events like Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which began in late February when the quarter was already more than half over. The COVID-19 surge that prompted weekslong lockdowns in China's two largest cities, Beijing and Shanghai, occurred mostly after the first quarter had closed.

Importantly, Bartell added, it has been roughly four decades since the last period of sustained inflation in the U.S., meaning few in leadership positions at private equity firms or their portfolio companies have real experience managing through inflation.

"This will be a test of management's acumen to adjust and make decisions. You come out of this stronger than you went in, but not everyone is going to come out unscathed," Bartell said.

Lessons from the Great Recession

For clues to the near-term outlook on dealmaking, DePonte suggested it may be possible to draw lessons from the global financial crisis of 2007-2008, noting that the timing of fundraising and capital deployment was closely tied to the performance of buyout funds in that period.

Funds that made big investments just prior to the crisis and those with large legacy portfolios to tend to were preoccupied with rescuing portfolio companies at the cost of signing new deals. But newer funds and those that closed near the end of 2008 were in prime position to find relative bargains in the marketplace, DePonte said, noting that March of 2009 was, in retrospect, "the perfect time to buy."

Bartell said managers seeking to seize the moment will still have to carefully consider what today's valuations mean for the prospect of earning a decent exit multiple in three to five years. The other main area of risk is stricter debt terms from lenders due to rising interest rates, he said.

"The terms that buyers will borrow on are going to be much more restrictive, much stricter, which also increases the chances of financial distress," Bartell said.