S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

9 Nov, 2022

By Camellia Moors and Kip Keen

|

Uranium ore is transported from Cameco's McArthur River mine in Saskatchewan. |

A shortage of uranium amid a nuclear power resurgence could send ore prices up by about 25% by 2030, but skeptical miners may not aggressively expand production unless prices climb even higher.

|

The U.S., Japan and several EU countries have announced plans to extend the life of nuclear power plants and even expand fleets instead of shuttering them as scheduled, creating a potential boom for uranium producers.

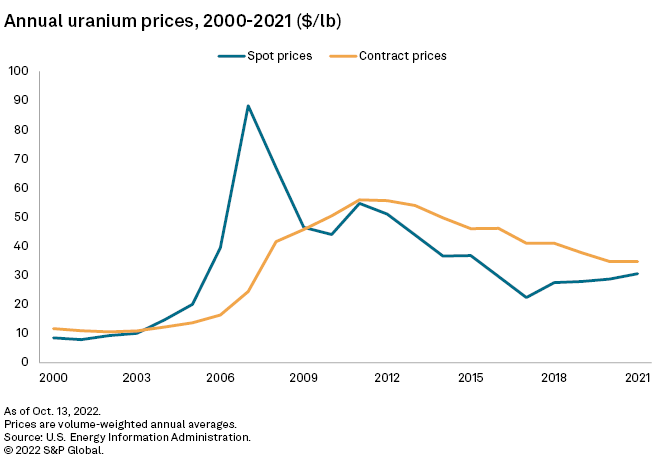

The uranium industry has been faced with a crash in demand and prices over the past decade after the Fukushima Dai-ichi plant in Japan went into partial meltdown in 2011 and countries began to move away from the fuel. While forecasters said uranium prices are likely to rise to $54 per pound by 2030, from about $50/lb in recent trading, miners are looking for uranium prices of at least $70-$75/lb before investing in major new capacity.

"What I hear the [uranium] miners saying is, 'Yes, we're standing ready and we're making the plans to potentially restart idle capacity, or, in the longer term, build up new mines,'" Laurent Odeh, chief commercial officer at Urenco Ltd., told S&P Global Commodity Insights, noting that other nuclear fuel processors were in a similar position. "But we will only do so when we have the certainty that the customer base is following it. And therefore we need the long-term contract for independent investment."

Uranium on rebound

Before 2021, prices for uranium dropped so low that Canadian producer Cameco Corp. and Kazakh producers idled capacity in 2017, with Cameco buying from the spot market to meet its longer-term contracts. In 2021, Sprott Physical Uranium Trust Fund formed and began vacuuming up uranium from the spot market at reduced prices.

Prices rose and fell on Sprott's activities, and some utilities now pay more attention to their contracting needs, some analysts said, noting that inventories of nuclear fuels have dried up amid increasing restarts. Cameco and Urenco said buyers are increasingly willing to ink longer-term contracts and uranium prices have picked up.

|

Uranium industry timeline |

Up until 2022, uranium producers had little reason to believe in new demand from power companies. Indeed, U.S. producers were reduced to begging the federal government to provide assistance to keep the few operational mines open, and in 2020, Congress authorized a national uranium reserve to guarantee annual purchases from U.S. companies.

But the tide appears to have shifted in favor of uranium producers, as some nuclear power heavyweights recalibrate their stances on the energy source.

Instead of a dead-end industry headed for widespread retirements outside of China, reactors are getting a second life. Countries such as the U.S. are turning to traditional nuclear energy and new small modular reactor, or SMR, technologies as sources of fossil-fuel-free electricity amid concerns over climate change, and to bolster energy security.

"We're seeing governments and companies return to nuclear with an appetite that I'm not sure I've ever seen in my four decades in this business," Tim Gitzel, Cameco president and CEO, said on an Oct. 27 earnings call.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which spurred crushing energy crises as Russia cut natural gas supplies, pushed some countries to delay plans to phase out nuclear energy and cut dependence on Russian nuclear fuels.

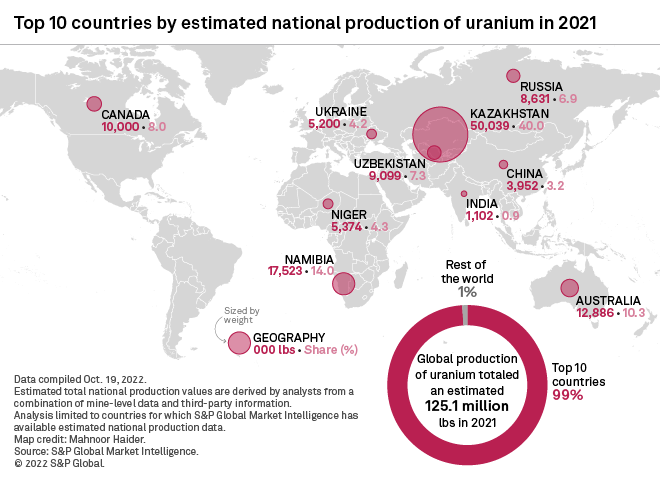

The invasion also pushed countries and fuel buyers to try to move away from uranium processed in Russia. The country accounted for about 39% of global enrichment capacity in 2022.

In the U.S., Sen. John Barrasso, R-Wyo., the top Republican on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee and a member of Senate leadership, introduced bills that would ban Russian uranium imports due to national security concerns.

These changes are creating optimism for non-Russian producers as uranium users seek to distance themselves from Russian suppliers.

"It is clear western utilities are not comfortable relying on Russian fuel and are considering more secure alternatives," said John Cash, CEO of Ur-Energy Inc. "We expect to see continued price volatility due to geopolitical issues related to Russia and potentially Kazakhstan. However, over time these issues will be resolved and a new normal will be found. It is unclear to what degree the new normal will exclude Russian processing."

Episodes of Energy Evolution are available on iTunes , Spotify and other podcast platforms.

Half-measures for now

The result of these shifts in the global uranium supply chain is that miners and nuclear fuel processors are encouraged by growing nuclear power commitments. In a boost for the industry, Cameco announced the restart of its McArthur River and Key Lake operations earlier this year, highlighting increased interest from contract buyers. Odeh said Urenco is working on plans to expand enrichment capacity, and that buyers had already sought it out to diversify away from Russia.

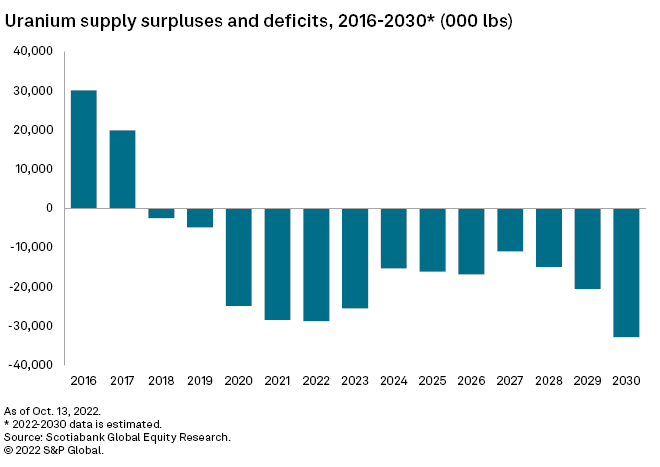

Pressure for new uranium mines will build, but not until later in the 2020s and into the 2030s, analysts said. After idled capacity comes back online over the next five years, uranium supply deficits will grow deeper starting in 2028, Scotiabank analysts said in a July 7 note.

These deficits may in turn support higher uranium and nuclear fuel prices and attract more mine-building cash. Consensus forecasts peg uranium prices at about the mid-$50/lb range from 2023 onward, hitting $56.40/lb in 2026, according to a recent analysis by Commodity Insights. But the industry is looking for far higher prices to justify more production.

"There may need to be significant price increases to incentivize all the mines that are needed," said Uranium Energy Corp. executive vice president Scott Melbye, echoing others in the sector. Industry veterans estimate the incentive price to be in the $70/lb-$75/lb range, whereas recent prices have hovered closer to $50/lb.

Rather than dig for new uranium, the industry is instead focused on dealmaking. Joe Mazumdar, a mining analyst and publisher of Exploration Insights, said it was telling that Cameco pursued vertical integration and expansion in downstream nuclear fuels in its recent deal to acquire a 49% interest in Westinghouse Electric Co. LLC.

Mazumdar also noted that the company made no play for the Roughrider project in Saskatchewan, despite having the right infrastructure.

Uranium Energy made a $150 million cash-share deal in October to acquire the Canadian uranium asset from Rio Tinto Group. Rio Tinto bought the property in 2011 in a $642 million deal, beating out Cameco in a bidding war.

A wait-and-see approach

Miners aren't seeing a rush of interest from nuclear utilities, either, who are waiting to see how the Russian invasion plays out and what it means for supplies out of Russia.

The bulk of utilities are "in a wait-and-see pattern, saying, 'Well, OK, the conflict is only six, seven, eight months old. Let's see what happens. But we want to talk to you more about potential long-term procurement,’" Odeh said, noting Urenco could increase capacity in 2027 and 2028 "under the right set of conditions."

Also uncertain are the new uranium demand cycles and enrichment requirements that could be created if countries adopt SMR technologies. Many of these reactors rely on high-assay low-enriched uranium and must be refueled on a different timeline than traditional nuclear reactors, which could upset the industry.

"We have some [SMRs] that use [high-assay low-enriched uranium], which basically means that instead of being enriched to four or five percent, it needs to be higher than that, and that has implications on the amount of uranium we need to mine and the fuel cycles that are going to go with it," said Matthew Crozat, executive director of strategy and policy development at the Nuclear Energy Institute.

In addition, miners are not getting the kind of investment they need to engage in the costly, risky process of new exploration.

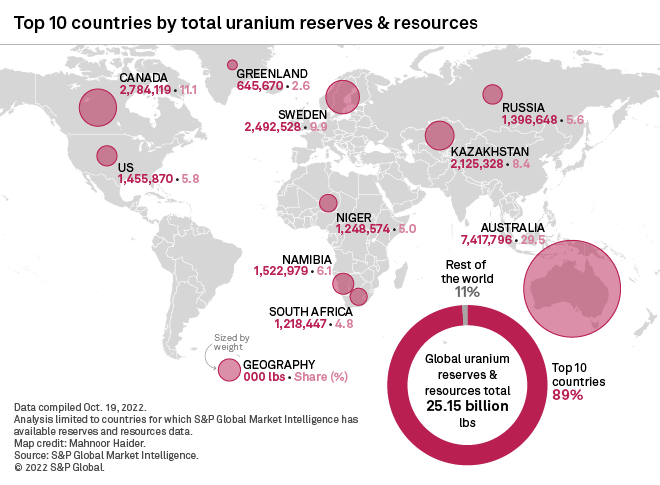

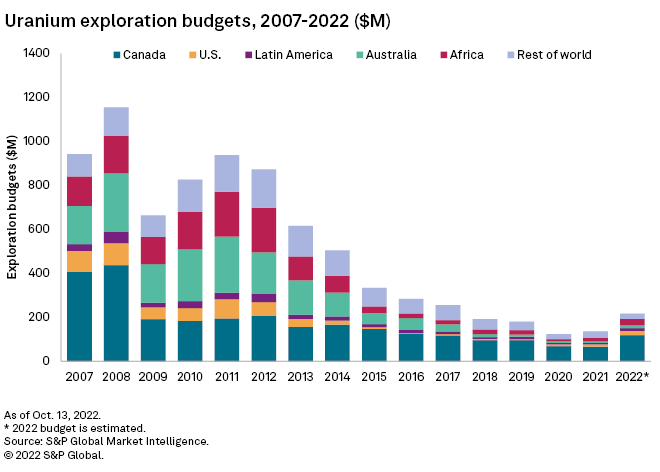

Spending on uranium exploration peaked in 2008, with budgets hitting $1.16 billion on the back of record uranium prices, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. The surge in funding over a decade ago helped drive a series of uranium discoveries, notably in Canada's Athabasca basin.

Interest in uranium exploration has waned in subsequent years, and Market Intelligence forecast 2022 uranium exploration budgets at $216.2 million. This is an improvement over exploration budgets in 2020 and 2021, but still a far cry from headier market days in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

"I do think that growth in uranium can keep pace with the growth of reactors, but it needs market signals, which will come," Melbye said.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.