Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

18 May, 2023

By Sanne Wass

The EU's new green bond standard is likely to see limited initial uptake as disincentives weigh on issuers.

|

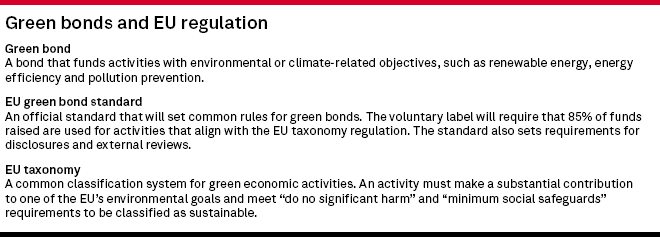

The voluntary label, which European Union negotiators agreed Feb. 28, aims to improve the transparency, comparability and credibility of the green bond market and aid its growth. It will dictate that 85% of funds raised are used for activities that align with the EU taxonomy regulation, while issuers will also have to meet requirements around disclosures and external reviews.

Yet the stringent criteria, data unavailability, high costs and potentially heightened liability risk mean many issuers will find it too difficult or risky to adopt the new EU green bond standard (GBS), market participants said. Uptake will be limited unless regulators address these issues, said Nicholas Pfaff, deputy CEO and head of sustainable finance at the International Capital Market Association (ICMA).

"There's a structural issue," Pfaff said. "There are so many criteria that are being required that it automatically leads to a narrow outcome."

Issuers face a particular challenge in meeting the taxonomy's requirements due to widespread data unavailability, according to a report published last year by ICMA, which represents financial institutions active in capital markets. The regulation also lacks assessment proportionality for smaller projects and businesses, which will be disadvantaged due to high costs and implementation challenges, the ICMA found.

"While we would like to issue bonds that comply with the EU green bond standard when in place, we see challenges in actually using the standard given the complexity of implementing all aspects of the EU taxonomy on the asset side," said Petra Wehlert, head of capital markets at German development bank KfW.

KfW's green bonds already meet most of the taxonomy's "substantial contribution" requirements, meaning the activities funded contribute to one of the EU's environmental objectives, Wehlert said. However, "we still have a data gap to bridge, especially with regard to 'do no significant harm' criteria," she said.

"Issuers are still struggling with the alignment of the use of proceeds with the EU taxonomy criteria," said Théo Kotula, environmental, social and governance analyst at AXA Investment Managers. While more and more issuers are including "substantial contribution" criteria in their issuance, it is much harder for them to align with the "do no significant harm" and "minimum social safeguards" requirements, Kotula said.

Even companies with sufficient taxonomy-aligned assets may be wary of adopting the GBS. Issuers will have to consider whether the using label will come with additional liability or reputational risks, especially given a growing focus from market stakeholders on greenwashing issues, said Ozgur Altun, associate director for sustainable finance at ICMA.

If issuers perceive it too difficult or risky to use the EU GBS, they may decide to continue using the ICMA market standard, which is currently followed by about 97% of issuances, as well as the additional certification provided by the Climate Bonds Initiative, Altun said.

The European Commission, the executive arm of the European Union, does not expect the standard to immediately gain widespread use.

"As a brand new standard, it is normal that uptake of the EU GBS will start low and build up over time, as bond issuers and external reviewers familiarize themselves with the rules for the standard and for the taxonomy," a commission spokesperson said. As more economic activities are added to the taxonomy, the types of green projects that can be funded by a European green bond will increase, which should also contribute to higher uptake, they said.

The usability of the taxonomy is "a key priority" for the commission, which will look to ensure that "rules are clear, coherent and as easy to implement as possible," the spokesperson said. This also includes improving data quality and availability.

First movers

Adopting the GBS could come with benefits for issuers. Higher demand for taxonomy-aligned assets from investors to meet their own sustainability and reporting requirements could drive a price benefit for issuers of GBS-labeled bonds, a so-called "greenium," Pfaff said. GBS-issuers may also enjoy reputational benefits, he said, while Bank of America analysts in a March 2 note said they expect EU GBS-aligned bonds to be less volatile over time.

EU sovereign, supranational and agency issuers are likely to initially test the GBS due to their policy support and involvement with the label, according to ICMA.

The utility sector could also be among the first to use the label because it generally issues green bonds to finance renewable energy projects, for which EU taxonomy criteria are "pretty straightforward and well known," said Kotula. Issuers that focus on low-carbon transportation and green building projects may also be among the first movers, as taxonomy criteria for those activities are well established, he said.

"Our expectation, and from other market stakeholders, is to potentially see the first EU GBS-aligned green bonds at the end of 2023, beginning of 2024," Kotula said.

A spokesperson for German utility E.ON SE said its green bond framework already fully complies with the criteria of the EU taxonomy regulation. "In general, we believe the implementation of a well thought through EU green bond standard may well provide further positive incentives for ESG-based financings to support the energy transition in line with the Paris agreement," they said. "Nevertheless, the implementation of the EU green bond standard still requires the concretization of details and regulations."

Investor demand

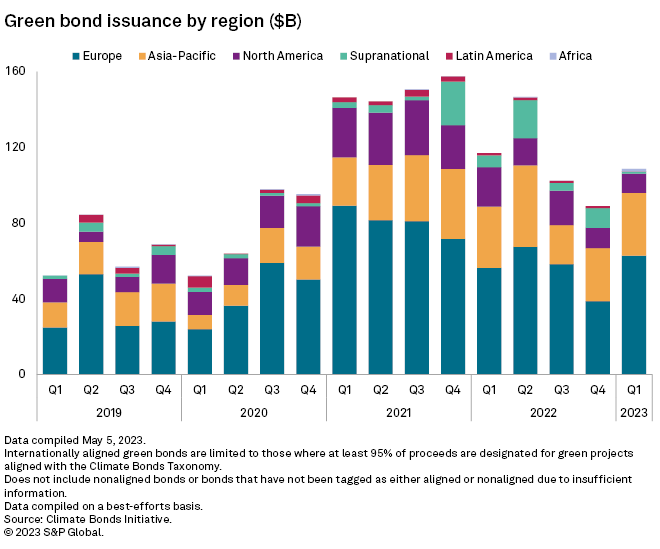

Europe has dominated the global green bond market to date, with issuance peaking at $323.40 billion in 2021, according to data from the Climate Bonds Initiative. For investors, an EU GBS label "would definitively be a plus," said Kotula. "The standard should definitely ease our discussions with issuers and help regarding the quality of green bonds, and as a result facilitate our analyses," he said.

However, AXA Investment Managers will continue to rely on its internal assessment methodology to assess the quality of green bonds, and will "keep investing in green bonds that do not comply with the [EU green bond] standard but that we believe are good quality ones," Kotula said.

Issuers may choose not to adopt the EU GBS but start by using the European Commission's voluntary disclosure opportunities released together with the standard, said Maureen Schuller, head of financials sector strategy at ING, speaking during a March 31 webinar.

The European Commission plans to publish disclosure templates for sustainable bonds so that, even if they do not make use of the EU GBS, issuers can report information on the taxonomy-alignment of their bonds.

Issuers may still decide to align their bonds' use of proceeds with the EU taxonomy, but without the EU GBS label, said Pfaff.

"What investors are looking for is the taxonomy alignment," Pfaff said. "So what could happen is issuers trying to come up with market practices around the concept of aligning with the taxonomy, but without exposing themselves to the other difficulties and potential liability of the EU GBS."