Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

18 Feb, 2021

By Jennifer Laidlaw and Francis Garrido

The green bond market will likely continue its upward trajectory, buoyed by a new climate-friendly U.S. administration, favorable EU regulation and net-zero emission targets by an increasing number of countries.

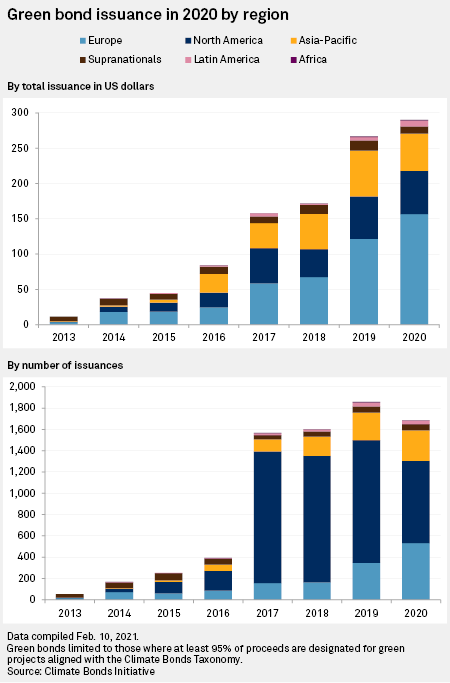

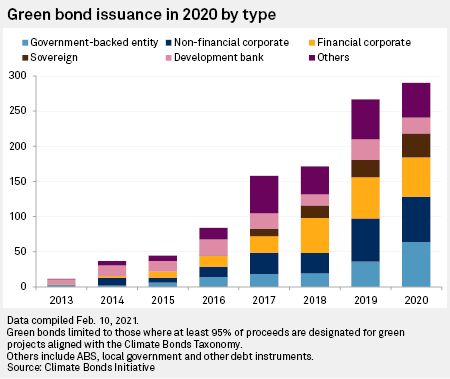

Although they represent a tiny fraction of the overall debt market, green bonds — debt that finances environmentally friendly projects such as wind farms or solar power — have grown rapidly over the last eight years, from virtually nothing in 2012 to $282.05 billion in 2020, based on figures from the nonprofit Climate Bonds Initiative, which promotes green investment.

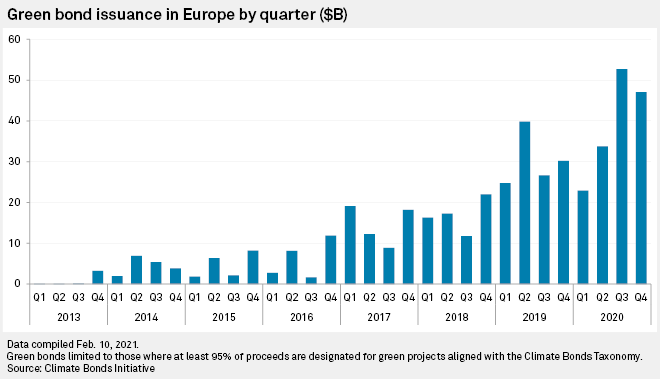

The market suffered a setback in 2020 as a March market rout sent green bond issuance into a tailspin, and issuers favored social bonds — debt instruments that finance social projects, including affordable housing, health and education — in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. However, green bonds recovered toward the end of 2020, surpassing the $266.5 billion achieved in 2019, boosted by sovereign and corporate issuance in Europe.

'Green agenda'

While U.S. corporates and financials have historically not been "huge issuers" of green bonds, the arrival of U.S. President Joe Biden in the White House should have a positive impact on the market, Kay Hope, a credit research analyst at Bank of America, said in an interview.

"For the last four years, we had an administration that didn't particularly value a green agenda," she said. "We don't have regulation pushing a green agenda like we do in the EU."

Biden has pledged to take an aggressive stance on climate change, and on his first day in office he took executive action to have the U.S. rejoin the Paris agreement on climate change, which aims to limit global temperature rises to less than 2 degrees Celsius.

Europe currently has the largest share of the green bond market, with the region issuing $151.70 billion in 2020 compared to $61.51 billion in North America.

"The U.S. will give [Europe] a run for its money if the U.S. starts issuing green treasuries. I don't really expect that to be happening until 2023," Climate Bonds Initiative CEO Sean Kidney said in an interview. "That would be huge."

The EU has generally been ahead of other regions in tackling climate change. In 2019, its presented its European Green Deal, designed to mobilize at least €1 trillion of sustainable investment over the next 10 years. In 2018, it launched its sustainable finance action plan, including creation of a classification system — or taxonomy — for green investments and an EU green bond standard. The coronavirus pandemic has underscored the EU's commitment to green finance, as it aims to spend 30% of its €750 billion EU recovery fund on climate-related projects. The EU plan will be a key driver of green bond growth, Kidney said.

Taxonomy, net-zero targets to drive growth

The EU taxonomy will also play a central role in market growth. Businesses with activities not considered taxonomy compliant could issue green bonds to help fund capital expenditures that would be in line with the taxonomy, Hope said.

"All this change and climate mitigation and adaption is going to be super important in the 2020s," Hope said. "How are you going to pay for it?"

Several countries have set net-zero targets, which could also drive green bond issuance. The EU, along with Japan, South Korea and more than 110 countries have pledged to be carbon neutral by 2050, meaning that their carbon emissions will not have a negative impact on the environment; China expects to to meet that target by 2060.

That will require massive investment, and green bonds are one of the instruments that could contribute to net zero goals, experts said.

"If countries are serious about zero emissions happening in 2050 or 2060 — and all the major economies of the world seemed to be committed to that target — it will require a massive investment in new technologies on a scale that we have never seen," Thomas Thygesen, head of research for climate and sustainable finance at Swedish bank Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken AB, said in an interview.

"If you want to achieve zero emissions not just when you produce energy but across the whole supply chain of your economy then you need to invest at least as much in those other areas, and governments also have a very strong interest in mobilizing private capital for transforming ... all sectors," he said.

Social and sustainability bonds

The market could be poised for expansion in other kinds of sustainable debt as well.

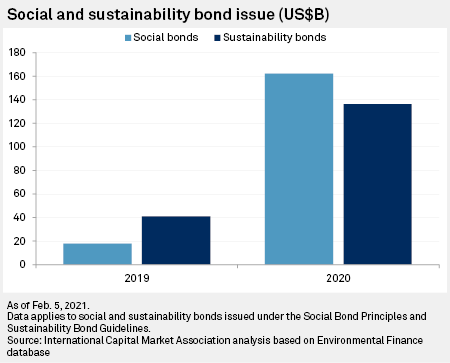

Social bond issuance blossomed in 2020 to reach $162.34 billion, up from $17.81 billion in 2019, while sustainability bonds also enjoyed a surge, with issuance rising to $136.40 billion, up from $40.99 billion, according to an International Capital Market Association analysis of the Environmental Finance database. Sustainability bonds are a hybrid of green and social bonds.

'Gold dust'

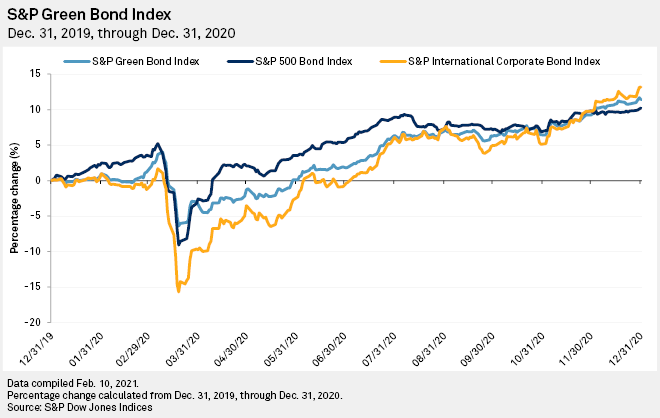

Key green bond indices demonstrate that green bonds can hold their own against other indices. The S&P Green Bond Index outperformed the S&P International Corporate Bond Index through much of 2020, though the latter pulled ahead at year-end. The S&P Green Bond Index ended the year higher than the S&P 500 Bond Index.

Historically, green bond supply has failed to keep up with demand as institutional investors have increasingly applied environmental, social and governance criteria to their investment decisions, leading to tighter pricing for the debt instrument, especially on the primary market when the bond is issued.

Kidney said green bonds are demonstrating more attractive pricing than vanilla bonds, and that in the March market rout, green bonds remained liquid, with some investors unable to sell any other form of debt.

"That is gold dust," he said. "That is driving the type of pricing, the tighter spreads at primary which we are seeing in a lot of currencies. All this has become self-fulfilling ... Issuance is going to grow and investors are going to keep piling in."