Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

27 Dec, 2021

By Karin Rives

| Flames from a flaring pit near a well in the Bakken oil field in North Dakota. Satellites are gathering methane release data from the oil and gas industry. Source: Orjan F. Ellingvag/Corbis News via Getty Images |

As satellites deliver more accurate data on methane emissions from oil and gas production, scientists are getting a clearer picture of how natural gas stacks up against coal and whether it is truly the cleaner fuel.

Researchers are refining their understanding of the point at which methane leaks along the gas chain offset the climate benefits of switching from burning coal to natural gas to generate electricity.

"I think the main breakthrough is that we're starting to be able to put numbers to it," Yasjka Meijer, a scientist with the European Space Agency's Copernicus program, said. Meijer has looked at comparisons of carbon dioxide emissions from coal plants versus life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions from the production and burning of natural gas.

Methane, the main ingredient in natural gas, carries more than 80 times the warming punch of carbon dioxide for the first 20 years, an impact that matters in climate planning scenarios at all levels, from utilities to nations.

Scientists caution that research into ongoing methane emissions is in the early stages, noting that uncertainty remains around which sources are responsible for the rapid buildup of methane in the atmosphere. Accidental blowouts from oil and gas fields and releases from coal mines are likely major contributors, however.

But over the last several years, readings by a growing fleet of satellites circling the Earth have also revealed that some normally functioning facilities are releasing significantly more of the climate-warming gas than what official greenhouse gas inventories suggest.

"We're able to pinpoint it down to specific sources, and in some cases, we've seen the quantification," Meijer said.

Satellites gather data

Meijer estimated that if 3% to 4% of natural gas produced at oil and gas wells leaks into the atmosphere, power produced by natural gas plants is on par with coal plants in terms of the overall climate impact. If upstream emissions exceed that percentage, natural gas would be more harmful than coal in the short term.

Another study by German researchers published in the journal Nature in June 2021 concluded that methane leakage below 4.9% would still give natural gas a leading edge over coal. A research paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2012 put the threshold at 3.2%.

One 2020 study modeling satellite observations of methane releases across North America found that operators in the prolific Permian Basin released 3.7% of the gas they extracted in 2018 and 2019. Based on Meijer's calculations, the life cycle of that natural gas — from the well to the power plant stack — would have roughly the same climate impact as coal would from mine to plant.

Another six-year study found that older production wells in the Uintah Basin in northeastern Utah emitted 6% to 8% of the gas they extracted, twice the break-even threshold in Meijer's estimate. Research from other areas has estimated a leak rate closer to 2.3%.

The persistent problem of methane plumes from oil and gas production fields in the Permian Basin has also been documented by the Environmental Defense Fund, a group advocating for stricter pollution controls. Its latest aerial survey released Dec. 13 showed that 40% of 900-some production sites are continuously leaking methane into the atmosphere.

'Possible' undercounting

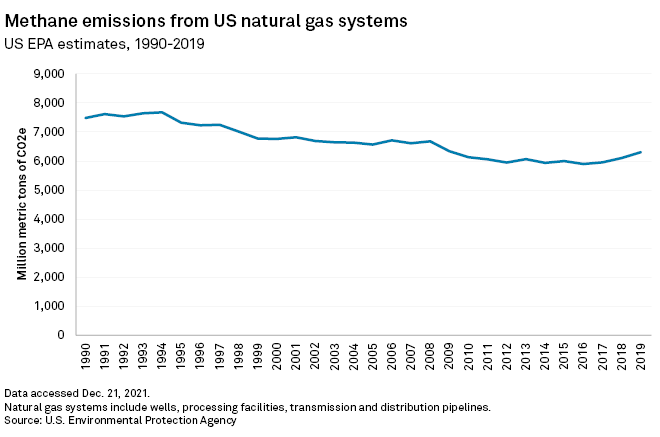

The EPA calculates industry's methane emissions by measuring leaks from a limited number of sites and by collecting data the industry self-reports. From there the agency extrapolates national data. The method has been challenged by researchers and environmental groups in recent years.

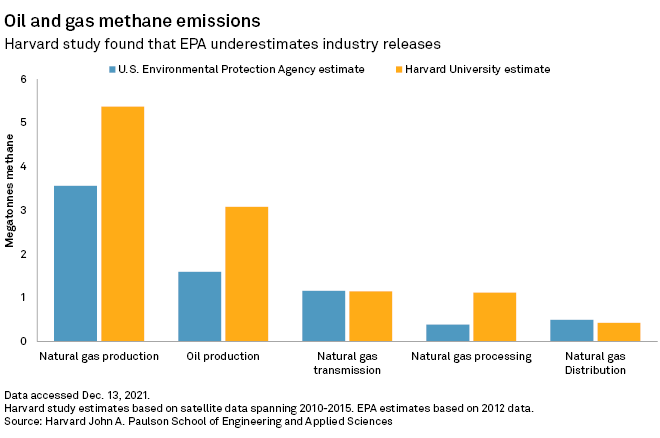

A 2021 Harvard University study looking at satellite data found methane emissions from oil production to be 90% higher and natural gas production 50% higher than the national data that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has been reporting to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

The Harvard study was the first to confirm on a national level what regional studies had shown before: The government's official inventory of methane emissions from oil and gas production sites underestimates how much they actually release. The EPA, in an email, acknowledged as much.

"Given the variability of practices and technologies across oil and gas systems and the occurrence of episodic events," EPA Deputy Press Secretary Tim Carroll said, "it is possible that the EPA's estimates do not include all methane emissions from abnormal events."

The methane problem is an irritant for power companies that continue to shift to natural gas as a cleaner alternative to coal, and the power industry has applauded proposed regulations to rein in leaks from wells, pipelines and processing plants.

"We are working to get the energy we provide as clean as we can as fast as we can while maintaining the reliability and affordability that our customers value," Tom Kuhn, president of the Edison Electric Institute, said in November when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed new and stringent methane curbs on the oil and natural gas industry. "Federal regulations on methane emissions across the value chain are essential."

A number of electric utilities are also zeroing in on their own natural gas infrastructure and supply chains. Xcel Energy Inc. announced in November that it would cut emissions from its natural gas service by 25% by 2030 from 2020 levels and only source gas from certified low-emission suppliers.

Sempra is developing upstream "preferred source" programs to procure more cleanly produced natural gas as well. Dominion Energy Inc. sold most of its natural gas transmission and storage facilities in 2020 and plans to sell the Questar Pipeline Co., part of the utility's plan to cut methane emissions 65% by 2030 below 2010 levels.

The demand for responsibly sourced natural gas is not lost on the industry: At least two dozen North American operators have thus far pledged to certify their products.

And the One Future Coalition — a group of companies spanning the natural gas value chain and representing roughly 19% of the gas produced in the U.S. — set a 2020 methane intensity goal of 0.283%. The group said its methane intensity, or leak rate, for that year came in at 0.105%.

Scientists like Meijer say they hope the scrutiny of the natural gas supply chain will prompt policies that end methane leaks once and for all. Indeed, such efforts now have broad support from previously reluctant U.S. industry players.

The oil and gas industry's main trade group is generally on board with methane reduction plans. In comments on the proposed methane emissions reduction policy, the American Petroleum Institute said methane reductions are a priority for the industry, albeit while urging the EPA to consider costs and implementation timelines.

Regulations could also help to tamp down criticism against the country's booming production and exports of liquefied natural gas, the group suggested.

"We believe the direct regulation of methane can further bolster the environmental benefits of American natural gas," Dustin Meyer, API's vice president of natural gas markets, said in an emailed statement. "Exports of U.S. LNG could help drive down global emissions by replacing dirtier fuels and higher-emitting Russian natural gas to our allies abroad."