Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

14 Jun, 2021

By Bill Holland and J Robinson

|

This is the fifth in a multipart series exploring the natural gas industry's role and prospects in the energy transition — a globe-spanning movement to cut greenhouse gas emissions across the energy industry.

The transition to a low-carbon energy future raises tough questions for the U.S. upstream natural gas industry about its environmental impacts and measures to mitigate them. The shift also threatens to end nearly 20 years of growth in gas production.

The low-carbon narrative has become a recurring theme among upstream companies and their investors, cropping up across conferences, investor presentations and earnings calls. In the 2020s and beyond, that narrative promises to dramatically alter the shale gas producer business model.

Throughout the early 2000s, the stunning success of shale drilling was supported by institutional investors and politicians directing capital and tax incentives to the upstream sector. This investment has allowed U.S. producers to nearly triple domestic output since the early 2000s to more than 90 Bcf/d currently.

As boardrooms and legislatures now scrutinize the carbon costs of drilling, producers' mandate for the 2020s is one of discipline and stewardship. First and foremost, low-cost, maintenance-level production will remain key to survival. Beyond that, though, intensive carbon-tracking and emissions reductions will likely become critical to success.

Low prices, narrow margins

Cheap gas — and the high costs to overhaul or repurpose midstream and downstream infrastructure — will likely make the fuel a fierce competitor to alternative energy sources, even in a low-carbon world. While the push toward renewable power will erode market share for gas in the generation sector, the fuel is forecast to remain robust in both the residential-commercial and industrial markets over the next 30 years.

For the upstream industry to hold onto that competitive edge, the sector will need to pursue further improvements in efficiency and cost-control.

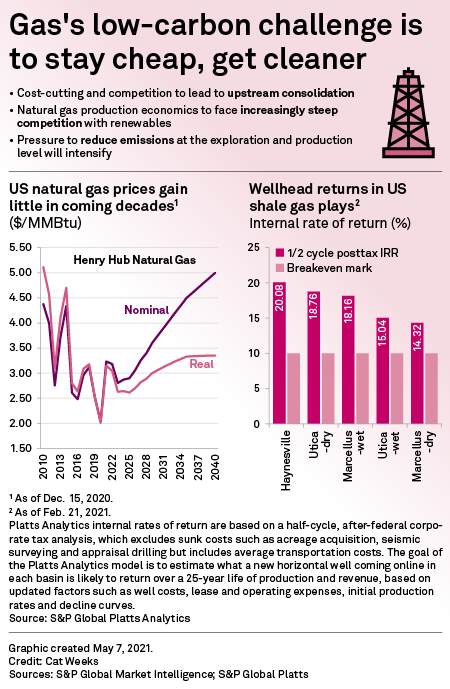

Over the past decade, the price of benchmark Henry Hub gas has averaged just $3.01/MMBtu, according to S&P Global Platts data. Consistently low prices have long been the hallmark of shale drilling, and through 2030, the real, inflation-adjusted, price of benchmark Henry Hub gas will average just $2.85/MMBtu, according to a forecast from S&P Global Platts Analytics. Over the decade that follows, prices will likely rise by less than 45 cents.

Already, low gas prices have rendered obsolete some of the most prolific early era shale basins, such as the Fayetteville Shale in Arkansas and the Barnett Shale in Texas. In the decades to come, that trend will only accelerate as producers focus on a narrowing pool of profitable resources in a handful of plays. These are likely to include the Delaware and Midland sub-basins of the Permian Basin in Texas and New Mexico; the Bakken Shale, largely in North Dakota; the Marcellus Shale in Appalachia; and the Haynesville Shale in Texas and Louisiana.

As of first-quarter 2021, an average shale producer in the Delaware Basin — currently the most profitable in North America — sees an internal rate of return close to 34%, based on a half-cycle, post-tax analysis. Across Appalachia, the average producer gets closer to 14% to 19% — just enough to remain profitable.

In recent years, average IRRs in even the most prolific basins have at times dipped lower — into the single digits, sometime for months. Generally, producers require a return of at least 10% to achieve breakeven, making margins below that level unsustainable longer term, according to Platts Analytics.

Consolidation, environmental stewardship

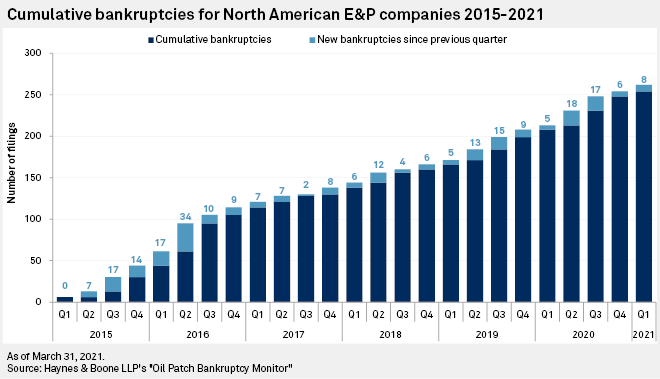

Over the next decade, thin margins and a growing focus from investors on profitability will likely narrow the field by way of bankruptcies, mergers and acquisitions, leaving only the most efficient standing.

Bankruptcies among U.S. exploration and production companies totaled eight in the first quarter of 2021, according recent data published by Haynes and Boone. It was the most for any first-quarter period since 2016, but still down from peak levels in the second quarter of 2020 when 18 E&Ps filed, and the third quarter that year when 17 bankruptcies were filed.

Even for producers that have weathered the storm, consolidation pressures in the 2020s are only likely to grow as the need for scale becomes increasingly critical to producers' survival in a low-price commodity environment. "In Appalachia, we've got 30 teams running around 30 rigs; you may have very efficient companies, but when you look at that, it could be more efficient than that," EQT Corp. President and CEO Toby Rice told analysts this year.

Cost, efficiency and consolidation pressures are just half of the equation for E&Ps, though. In the 2020s and beyond, discerning investors and tighter regulations will demand environmental stewardship, too.

For natural gas producers, emissions detection, tracking and certification at the wellhead and on gathering lines will become a necessary, routine component of environmental stewardship. Beyond that, investors will look to E&Ps for leadership in the adoption of low- or zero-carbon business models and emissions-cutting technologies.

This spring, the U.S.'s largest gas producer, EQT, already took its first step in that direction, saying its Marcellus output would undergo an independent assessment of its environmental impact. Its certification will include quantified assessments for methane detection and intensity, along with an overall score based on other factors, including the company's record on corporate governance, ethics, social impacts, human rights, community engagement, biodiversity and climate change. Last year, BP PLC announced an ambitious goal to achieve carbon neutrality for its business by midcentury.

The push for greater environmental stewardship comes not just from investors but from end-users, too. Earlier this year, Pavilion Energy Pte Ltd. signed a six-year LNG sales and purchase agreement with Chevron Corp. for the supply of some 500,000 t/y of LNG to Singapore starting in 2023. Under the agreement, cargoes delivered will be accompanied by a statement of greenhouse gas emissions measured from the wellhead to the discharge port. At a recent climate summit, Chevron's general manager of ESG and Sustainability said that he anticipates many future commercial deals will include such agreements.

For some E&Ps, pressure has intensified in recent weeks. At Exxon Mobil Corp. — which has announced its own plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions some 30% by 2025, with reductions coming in part from carbon capture and sequestration technology — an activist hedge fund managed to get three nominees onto the Exxon board. The same day, Chevron investors voted for stringent targets to cut emissions from the company's products, and Royal Dutch Shell PLC was handed a court decision in the Netherlands ordering the company to accelerate emissions reductions and cut its carbon footprint by 45% globally by 2030.

Environmental initiatives are already becoming business-critical for E&Ps as they look to attract both investor dollars and end-user customers, and the sector can expect more of the same into the mid-2020s and beyond.

J Robinson is a reporter for S&P Global Platts. S&P Global Market Intelligence and S&P Global Platts are owned by S&P Global Inc.