Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

10 Feb, 2022

| Georgia Power Co. has proposed retiring more than 3,500 MW of fossil fuel-fired capacity by the end of 2028, including unit 3 at the 3,440-MW Scherer plant in Monroe County, Ga. Unit 4 was shut down at the end of 2021. The retirements will reduce the plant's operating capacity by 1,720 MW. Source: Georgia Power Co. |

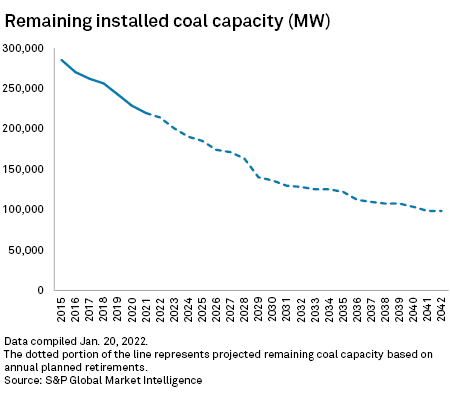

U.S. coal-fired generating capacity is set to take a record plunge in 2028 in advance of tough environmental rules, with more than 23 GW scheduled to come offline, dwarfing the previous retirements record set in 2015.

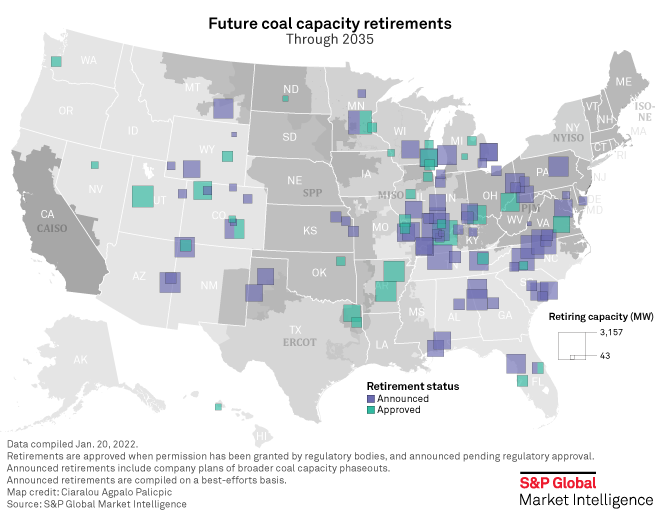

Under price pressure from renewable power and a national move away from high-emission fuels, utilities plan to shutter 51 GW of coal power from 2022 through 2027, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence analysis. But in 2028 alone, retirements will jump by 23 GW, and that doesn't include the retirements of the 1,700-MW Conemaugh and 1,700-MW Keystone coal-fired power plants in Pennsylvania that were reported by media. As in 2015, when a rule establishing strict mercury emissions limitations went into effect, plants will be shuttering to avoid complying with new environmental rules.

"It's going to get worse before it gets better," said Steve Piper, director of energy research at Market Intelligence. "We're going to see more retirements coming up."

The collapse in the cost of wind and solar power along with years of low natural gas prices left coal power a high-priced, high-emissions source of electricity. Power generators are increasingly building solar and wind resources when retiring coal-fired power plants. Utilities have already been retiring their coal plants at a rapid clip, with 71.4 GW of coal-fired power plant capacity taken offline since 2015. In particular, the midwestern U.S. is set to lead the next wave of power plant retirements as plants age and their prospects appear increasingly dim.

|

|

"No utility wants to put capital into coal plants these days," Morningstar analyst Travis Miller said in a recent phone interview. "Once you start putting capital into coal plants, you need those plants to run for 30 or 40 years before you get that capital back through depreciation."

As of June 2021, the average capacity-weighted age of U.S. coal-fired power plants was around 42 years, Market Intelligence analysis showed. The capacity-weighted average age of retirement for U.S. coal plants since 2002 has been around 50 years, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The ELG effect

The U.S. coal industry has been besieged by a federal push to reduce emissions. After four years of favorable attention from President Donald Trump failed to stem the wave of retirements, the sector must now deal with President Joe Biden, who has promised to achieve a power generating sector with net-zero emissions by 2035. Biden's agencies have acted to help make that a reality. Early in 2021, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency denied extensions on coal ash facility closures and moved to restore the legal basis for a mercury emissions rule that was set aside by the Trump administration, both of which raised costs for coal power plants already straining to stay financially afloat.

A contributing factor to the spate of closures lined up for 2028 is that coal-fired power plants must comply with the EPA's Effluent Limitation Guidelines, or ELG rule, for regulating coal ash and toxic metals in wastewater no later than Dec. 31, 2028. Under Trump, coal plants were given a special exemption to effluent rules and were able to keep their waste in surface-level ponds if the plant retired by the end of 2028. Effluent rules are intended to keep pollution out of drinking water.

Paul Chodak, executive vice president of generation for American Electric Power Co. Inc., or AEP, said federal ELG and coal ash regulations were strong factors in the utility's decision to retire its 675-MW Pirkey coal plant in Texas in 2023 and its 2,600-MW Rockport plant in Indiana, and to cease burning coal at its 1,056-MW Welsh facility in Texas in 2028.

Chodak said making the necessary investments to keep those plants online and comply with environmental regulations "was not justified" when compared to forecasted market prices and alternative primarily renewable resources.

In line with its market contemporaries, AEP's resource mix has shifted away from coal in recent years. The Columbus, Ohio-headquartered investor-owned utility had 24,800 MW of coal capacity in 2010, which was reduced to 12,100 MW in 2020. AEP expects to have about 6,500 MW of coal capacity in 2030.

"Our goal is to reduce that more," Chodak said. "The limitation is economics. It's the cost to our customers to do that and then the other limitation is to make sure we have reliable power."

Coal power's future

In late 2021 and early 2022, coal-fired power plants got a boost as higher natural gas prices made them more economic, a situation that seems likely to persist for the near term.

Miller said the PJM Interconnection LLC is "an interesting market to watch because you have a lot of brand-new gas plants operating on what was cheap gas but is not all that cheap anymore." The PJM Interconnection is the largest U.S. power market, covering 13 states.

"You've got a fairly large fleet of coal plants that now looks a lot more economic than it did three years ago," Miller said. "I think policymaking is going to be the real deciding factor in how long coal plants stick around in that region."

But the coal industry is in such deep decline that some plants have been unable to supply the market in order to preserve their coal stockpiles.

|

"It's hard to get equipment and hard to get employees, so the increase in production has been modest, but they're struggling to maintain and even increase production in the near term," said Matt Preston, research director for North American coal markets at consulting firm Wood Mackenzie. "We've had this cold winter, so stockpiles are going to be really low. In fact, I think if it continues much [further] into February, there's a good chance some coal units are going to go offline because they don't have enough coal."

Coal plant operators have also held out hope for years that carbon capture technology would become cheap enough to let them burn coal with far fewer carbon emissions, but the technology has not yet been sufficiently established.

"I don't know that utilities can bank on that as a tool that they're going to have in their tool belt in the timeframes that it's needed," Julia Hamm, president and CEO of the Smart Electric Power Alliance, said in an interview.

The coal power plant base will likely continue to atrophy.

Chodak said it's possible that some fossil plants may hang on, but they might run as little as five days each year to meet peak loads during winter storms or summer heat waves.

"Our goal is to transition to clean energy," Chodak said. "Even where we're not reducing our capacity, we're trying to reduce our megawatt-hours coming out of fossil plants, in particular coal."