Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

5 Jul, 2023

By Taylor Kuykendall and Kip Keen

|

Artificial intelligence could be the key to locating the next sources of tomorrow's materials, according to some experts. |

Mining companies are testing the potential of artificial intelligence to discover new sources of high-demand metals, but data constraints threaten to stymy the technology's usefulness, some experts said.

A growing need for metals and other materials used in electric vehicle batteries, grid-scale energy storage, transmission lines and other applications could bottleneck the world's transition to cleaner energy. Against this backdrop, experts in AI and mining are weighing rapidly advancing AI technology as a method to unlock discoveries of these critical materials, particularly as uses of deep learning technology such as ChatGPT spread throughout the global economy.

Deep learning, a type of AI that includes generative AI such as ChatGPT, uses artificial neural networks to crunch data using methods similar to a human brain as it learns how to perform tasks and model complex systems. Deep learning models rely on vast quantities of data and feedback to function, however, and exploration is inherently a low-feedback, hunch-driven process where the path to successful discoveries is tough to define. What is more, the mining sector tends to be conservative in adopting new technologies.

"AI has the potential to transform the industry at a multitude of levels," said Joe Carr, mining innovation director at Axora, a marketplace for heavy industry technologies. "However, there is a large hesitation to move forward, as people are concerned about how effective it might be and the impacts should it go wrong."

Help wanted

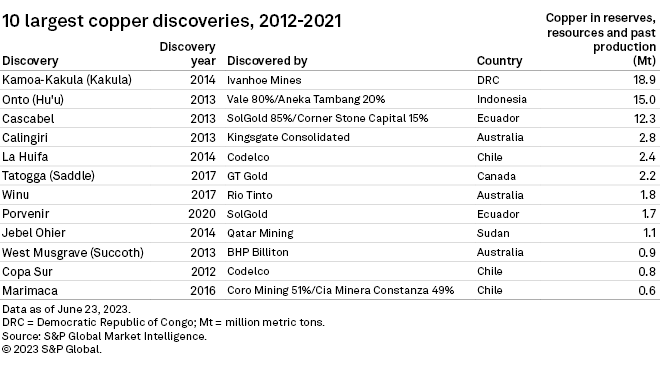

Miners and explorers could use the assistance. The mining sector faces a drought in discoveries, especially for key energy transition metals such as copper, which is crucial to electrification. There were 228 copper deposits discovered between 1990 and 2021, and all but 12 deposits were found before 2012, accounting for 94.7% of post-1990 metal in copper discoveries, according to an S&P Global Commodity Insights research analysis released in May 2022.

Meanwhile, copper production is set to fall short of industry needs into the 2030s as consumers buy more metal-intensive electric cars and countries bolster metal-rich infrastructure such as power lines. It is a similar picture for other metals including lithium.

"With copper demand expected to outpace refined copper production, the industry is not making enough new, high-quality discoveries to support the long-term pipeline," Sean DeCoff, a Commodity Insights analyst, said in the May 2022 report.

AI's growing reach

The mining industry has been dabbling in various AI technologies for years, including deep learning, and some large miners have already deployed AI and other advanced computing solutions in wide-ranging projects.

That includes Freeport-McMoRan Inc., which used AI-assisted systems at its Bagdad mine in Arizona in 2018 to test capacity levels at its mill. The company said in July 2020 that the project had increased copper output levels at the site by 9,000 metric tons.

Rio Tinto Group employs "digital twinning" to create virtual mine models to test in-the-field decisions ahead of execution. And the company has boosted productivity by combining AI with analytics, machine learning and automation to assess the data generated by its drills, trucks, shovels, conveyors, trains and ships.

In exploration, a growing slew of companies aims to leverage AI, including Canada's ALS GoldSpot Discoveries Ltd., Australia- and US-based Earth AI, and Tomra Systems ASA in Norway.

Goldcorp, which merged with Newmont Corp. in 2019, worked with IBM Canada in 2018 to develop AI software to predict where to dig for gold mineralization at the Red Lake mine in Ontario. California-based KoBold Metals Co. also uses AI for mineral exploration, and the company recently reached unicorn status with a $200 million fundraising round pushing its value over $1 billion, The Wall Street Journal reported June 20.

However, recent developments in generative AI software such as ChatGPT have stirred up a wave of interest in the near-term capabilities of AI, capturing the attention of investors and the industry as a whole.

AI can process volumes of data that would prove dizzying to humans, and the ongoing digitization of older datasets is increasing the potential power of AI-driven exploration, Carr said. "The benefit of AI is that it can see what humans simply don't have the capacity to see," Carr said.

Deep learning AI even has the potential to beat human experts in geology, according to Manolis Kellis, head of the MIT Computational Biology Group and a principal investigator with the university's Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab.

"If you give machines the data necessary, and you give them enough ... ability to learn representations [and] to choose what representations are meaningful for specific tasks, they'll be able to surpass the best geologists, or at least 90% of geologists," Kellis said, looking to the near future.

Data desert

But AI faces a daunting challenge in driving new discoveries because there is so little data on what leads to exploration success, said Benjamin Cox, an industry consultant and head of mining solutions at Open Mineral. Cox thinks that AI is an excellent tool for doing things like helping flesh out known deposits, blocking out or better defining resources and reserves, and managing mine processing. Cox is among the experts who doubt that AI will quickly become a talented prospector.

Time is part of the problem. The discovery-to-production cycle in mining occurs over decades and averages 15.7 years, according to

"AI needs enough wins to learn from to be successful," Cox said.

Duane Parnham, executive chairman and CEO of uranium exploration company Madison Metals Inc., said he was introduced to the concept of AI in mining applications years ago but was leery due to the industry's historical protection of its data. Parnham told Commodity Insights that he remains skeptical to what degree "armchair geologists" will replace more traditional mineral exploration.

"It's much easier to sit in a computer and geo-fantasize about what's going on, geologically speaking, than actually getting out into the field and banging rocks and really understanding the geological models," Parnham said. "Using AI is great, but it's just not your only tool."

Parnham added that it may only be the largest mining companies that can afford the computing power needed to support deep learning for exploration purposes.

Finding features

The surprising speed of advancements in deep learning has continually forced skeptics to shift the goalposts defining the limits of what deep learning AI has been able to achieve over the decades.

"If I had a penny for every time someone said machines will never be able to do that, I would be a billionaire," Kellis said.

Richard Inglis, Newmont's chief geoscientist, painted a picture of AI helping to reshape exploration mechanics and drive discoveries during his March 7 keynote address at the annual Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada conference in Toronto.

There is a lot of potential for generative AI to summarize important information from a sea of exploration reports going back over the centuries as they are converted to digital databases, Inglis said.

"The same technology can be used in mineral exploration and pull information from ... technical reports, government assessment reports, even the comments section of drill logs," Inglis said, referring specifically to ChatGPT. "And we know there's a lot of useful information hiding there."

In this, and through other applications, AI could help stem the industry's declining success rate in finding more metal, Inglis told Commodity Insights on the sidelines of the conference.

"I hope it will turn the tide," Inglis said.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.