Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

5 Sep, 2023

| Workers prepare for a 2007 reopening of the South Crofty tin mine, which has operated intermittently in the UK since the mid-1600s. Mining industry veteran Mick Davis recently invested £25 million in mine owner Cornish Metals as part of a wider focus on clean energy opportunities. |

Name-brand energy transition metals such as lithium and copper have drawn the attention of most mining investors, but some are looking into more niche elements, where navigating a dizzying array of minerals can present unique challenges.

The field of investors in major energy transition metals is crowded, with large miners making plays for copper and even oil majors such as Exxon Mobil Corp. wading into the lithium business. But materials such as rare earth elements, vanadium, graphite, scandium and manganese are critical for supplying magnets used in wind turbines or providing an essential part of rechargeable batteries. Investors targeting those types of metal must stake a bet on relatively small projects that are more complicated to mine, while the project developers need those investors as they struggle to increase a wider understanding of their products.

"These clean energy metals and minerals, many of them are actually very high-value commodities, commodities that don't require big infrastructure," Andrew Trahar, a co-founder of investment company Vision Blue Resources Ltd., told S&P Global Commodity Insights. "[They are] commodities that we can put on a truck and send down existing road infrastructure that doesn't require multibillion-dollar projects and can be built for a few hundred million dollars of [capital expenditure] in much shorter periods of time."

Looking for the unicorns

Mick Davis, founder of Vision Blue and a former mining executive and investor with a track record of building giant mining corporations, is digging through assets containing some lesser-known energy transition metals in hopes of building a stable of unicorns.

The mining veteran behind investment vehicle Vision Blue, Davis built Xstrata PLC into one of the largest mining companies in the world before it was sold to Glencore PLC. Davis, who was not available for comment, also played a crucial role with the executive team at the heart of a merger transaction that resulted in what is today BHP Group Ltd., the largest mining company in the world by market capitalization. Lesser-known commodities such as silicon, tin and graphite have all been pulled into Vision Blue's portfolio.

"If the lithium-ion battery were called the graphite battery, everyone would be piling into graphite," Trahar said. "I'm not trying to discount lithium's significant role to play. Lithium has a very important role in this transition. ... At the same time, every single anode in a lithium-ion battery is graphite today."

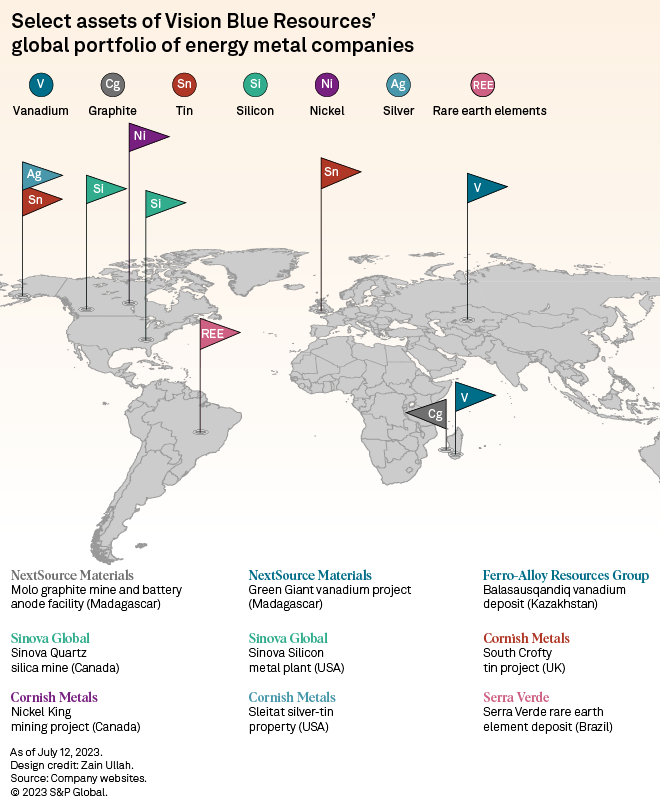

Vision Blue announced in April that it raised over $650 million from investors seeking exposure to the energy transition. Vision Blue's portfolio spans the globe, including a graphite project in Madagascar, a vanadium deposit in Kazakhstan, silicon assets in Canada and Tennessee, a tin project in the UK, and a rare earths asset in Brazil.

Investors looking in the corners

Most investors looking to invest in the energy transition struggle to get beyond the major battery metals such as lithium, nickel, copper and cobalt. Some are mystified by the complexities of things such as the lanthanide series of the periodical table, also known as the rare earth elements.

"There's still, I think, a lot of comfort among investors in terms of [copper]: How you extract it, how you process it, how it's priced, what its base demand is going to be, all kinds of things," said Cynthia Urda Kassis, a partner in the law firm Shearman & Sterling's project development and finance practice, where she is the lead industry coordinator for metals and mining. "With some of these [other] minerals, that's not the case."

It is also harder to invest directly in in rare earths and the other lesser-known energy transition minerals, as some are byproducts of other sought-after materials. That is the case for germanium, which is primarily produced as a byproduct of zinc and which received attention when China said in July that it would impose export controls.

Another example of a lesser-known commodity is antimony trisulfide, a mineral compound used in military munitions and other applications. The US Defense Department recently awarded $15.5 million in funding to Perpetua Resources Corp. to demonstrate what would become the only US-based source. Perpetua Resources plans to produce antimony trisulfide using ore mined from its feasibility-stage Stibnite gold project in Idaho.

"For a lot of these smaller metals, it's not the main product," said Ian Lange, an associate professor of economics and business at the Colorado School of Mines. "It's not what someone is going to invest in, generally, just because the quantities aren't big enough."

Rare earths, rare investors

Producers of these lesser-known materials must educate many of their new investors. Even those familiar with mining can struggle to invest in some commodities where demand is rapidly increasing, said Luisa Moreno, president of Vancouver, British Columbia-based Defense Metals Corp.

"I think, generally speaking, investors understand the geopolitical nightmare that we are in where China essentially controls the production and refining of many of the critical materials for the green agenda, whether that is rare earth or lithium," Moreno said. "Now what is very difficult for most investors, even for investors familiar with the resource space, is how to value a rare earth project."

Thras Moraitis, president and CEO of rare earth miner Serra Verde Mineracao Ltda., said the company faced similar challenges explaining the industry to traditional mining investors. Serra Verde, which is focused on its namesake, preproduction-stage Serra Verde rare earths property in Brazil, is another company in Vision Blue's investment portfolio.

"It's more like a chemical or industrial minerals business than a traditional mining business," Moraitis said. "So traditional mining investors have not historically been interested in rare earth, including the majors. ... We haven't seen major institutional funds invest in this type of activity yet, but I believe it's kind of a matter of time," Moraitis said.

That does not mean major diversified miners are not at least dipping a toe into investment in the lesser-known materials. For example, Perth, Western Australia-based South32 Ltd. is expanding its manganese production, banking on the energy transition requiring wider use of manganese-rich batteries.

However, while the industry takes shape, Vision Blue still has plenty of capital to deploy and can write fairly large checks when opportunities present themselves, said Craig Scherba, president and CEO at Canadian miner NextSource Materials Inc. The company's main assets include the Molo graphite operation in Madagascar, where production is ramping up after commissioning kicked off in March. Vision Blue agreed to invest in NextSource Materials in February 2021, with gross proceeds totaling $29.5 million earmarked primarily for the Molo development.

"We are very selective in the assets that we choose to back," Scherba said. "We need assets that acquirers will be fighting over in the fullness of time when the sector becomes hotter than it even is today."

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.