S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

26 Oct, 2021

Investors' expectations that the Federal Reserve will hike interest rates by the summer of 2022 are rapidly growing as inflation continues to run hot.

About 58% of investors on Oct. 25 expected at least one hike following the Federal Open Market Committee's June 2022 meeting, up from 16% a month earlier, according to the CME FedWatch Tool, which measures investor sentiment in the Fed funds futures market. About 18% expected the Fed to hike rates as soon as March, a jump from about 2% a month earlier.

Those odds have risen as inflation remains high. The consumer price index, the market's preferred inflation metric, has recorded an average increase of 5.4% year over year each month since June, driven by a supply chain crunch and rising energy prices. Continued pressures might leave the Fed with few policy options outside of ramping up the pace of the soon-to-begin tapering of its monthly securities purchases and preparing for an early rate hike.

"The Fed can't alter the supply-side dynamics," said Kathy Jones, managing director and chief fixed-income strategist with the Schwab Center for Financial Research. "It can't pump more oil, make more computer chips, or clear up the backlogs at ports, but it can hike rates to slow the demand-side if it looks like inflation is going to accelerate."

No ties to tapering

The federal funds rate, a benchmark for short-term lending for financial institutions and a peg for several consumer rates, has been kept near 0% since March 2020, part of the central bank's ultraloose monetary policy in response to the pandemic. The Fed is poised to begin tapering its $120 billion in monthly securities purchases — another pandemic-era measure — as soon as November with expectations that rates may rise after the program is wrapped in 2022.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has indicated a rate hike will not be tied to the end of tapering and is not a policy tool that central bank officials are considering yet to address rising inflation.

Still, half of the FOMC's 18 members expect at least one rate hike in 2022, according to the latest projections released by the central bank in September. Almost all investors expect at least one rate hike before the end of 2022, up from 75% in September, according to the CME FedWatch Tool.

The yield on the five-year Treasury note, another proxy for interest rate expectations, settled at 1.23% on Oct. 23. That was up 58 basis points from Aug. 3, when the yield closed at a near six-month low.

The data points show a growing, aggressive view from investors as inflation has climbed beyond earlier expectations, said John Canavan, a bond strategist for Oxford Economics.

"Markets have called into question the Fed's ability and comfort in keeping rates at the effective lower bound," Canavan said in an Oct. 21 note.

Speedier taper

The Fed could raise rates twice in 2022, once in September and again in December, after ending its tapering in June, said Antoine Bouvet, a senior rates strategist with ING. Elevated inflation and expectations of continued price pressures will increase the risk of earlier-than-expected hikes.

"The Fed could speed up tapering if it needs to make room for a hike in June, possibly even earlier," Bouvet said.

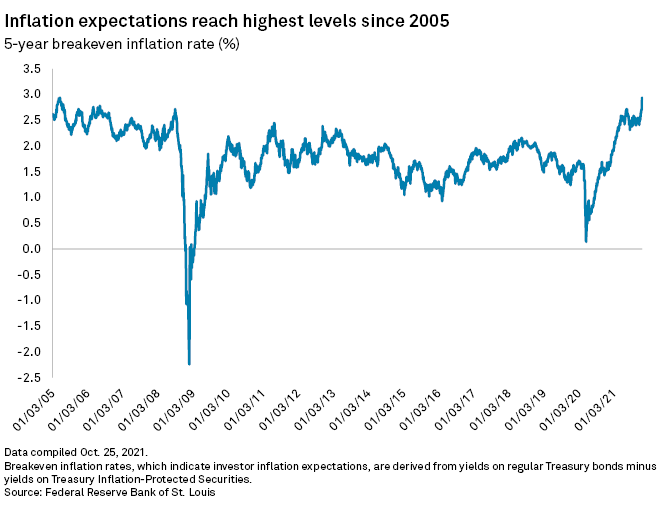

The five-year break-even inflation rate, a market-derived measure of average inflation expectations for the next five years, is at its highest level since 2005. Rising oil prices, COVID-19 variants, and historic supply-chain impediments have slowed the rebalancing of global supply and demand fundamentals, pushing prices up.

If inflation rises substantially more, the Fed may tighten policy earlier than expected, the Schwab Center's Jones said, noting that a rate hike, however, is a "blunt instrument" for the Fed, and officials may remain unlikely to pursue it due to its potential impact on U.S. equities and other markets.

A sooner-than-expected rate hike could also prove counterproductive, considering that price increases were being driven by logjams at ports and low oil supplies, among other factors, Steven Blitz, chief U.S. economist with TS Lombard, said in an Oct. 25 note.

"Higher interest rates imposed by the Fed do not reopen productive capacity," Blitz wrote. "In fact, by ramping up the dollar with aggressive rate hikes, import prices and domestic inflation fall off but at the cost of stagnating the domestic goods industry."