Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

14 Jan, 2021

By Ranina Sanglap and Rehan Ahmad

Major Australian banks face a tougher year in 2021, as their scaled-down operations following a spate of misconduct cases has left them with less cushion against high compliance costs, record low interest rates, elevated loan loss provisions and competition from nonbanks, analysts say.

Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd., Commonwealth Bank of Australia, National Australia Bank Ltd. and Westpac Banking Corp. have sold or are off-loading their wealth management and insurance businesses since the Royal Commission exposed their misconduct and violations of consumer rights in February 2019.

As their revenue sources are now primarily corporate and mortgage lending in Australia and New Zealand, the banks no longer enjoy the benefits of risk diversification and fee growth they used to have during the few strong years prior to 2019. As COVID-19 continues to rage, the banks may have a longer path ahead to regain their earnings momentum, analysts add.

The major banks are "banking on future growth from their lending, especially mortgage divisions," Martin North, founding principal and banking sector analyst at Australia-based Digital Finance Analytics, told S&P Global Market Intelligence.

"Future profitability is also being crunched by lower interest rates, though offset by cheaper finance from the Reserve Bank of Australia."

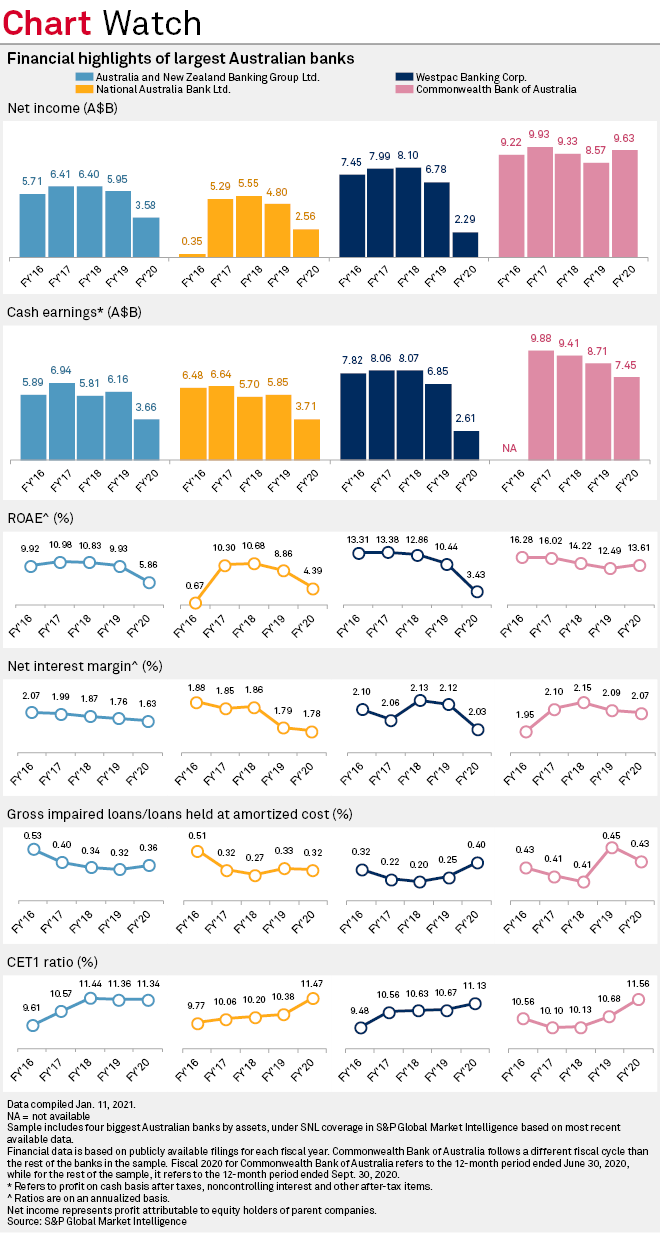

In the last fiscal year, the aggregate cash profit of the four major banks fell 36.6% year over year to A$17.4 billion from A$27.39 billion due to higher loan-loss provisions, customer remediation costs, and in the case of Westpac, a hefty fine on alleged money laundering. Net interest margins of the lenders fell to between 1.63% to 2.07%, from a range of 1.76% to 2.09% a year earlier, as the nation's central bank slashed the policy interest rates to a record low to counter the impact from the pandemic.

Margin, cost pressure

"Banks are expected to continue facing a number of large and complex remediation, regulatory changes and further competition from non-bank lenders," Yin Yeoh, senior industry analyst at IBISWorld, told S&P Global Market Intelligence in an email. Banks are also expected to lower fixed mortgage rates to better compete with non-bank lenders. "These trends are projected to constrain net interest margins for banks," Yeoh said.

Even with the Royal Commission behind them, the major banks are still expected to face increasing regulation, she said.

"Higher compliance costs and capital adequacy requirements are likely to be introduced over the next five years despite the major banks' continued exits from their wealth management businesses," Yeoh said.

The Basel III reforms have been delayed to January 2023 from January 2022. Australia deferred implementing some recommendations from the Royal Commission that were scheduled to be introduced in Parliament to June 2021 from December 2020 in light of the pandemic. Financial sector regulators, too, said they will suspend some of their prudential standards and reforms planned for 2021.

Costs are a big challenge for the big four as transactions move online and away from branches, North said, adding that banks may cut more staff, especially from middle management and customer-facing roles. The big four banks have seen costs remain high in fiscal 2020 and cost-to-income ratios increased to an average of 53.2% from 47.2%, according to a report from KPMG. The increase was driven by customer remediation and higher IT-related expenses.

The Australian major banks are now faced with real management challenges "as opposed to the almost automatic profit uplifts of recent years," he said.

Another big unknown for banks is the amount of bad debts in their books. Banks have increased their provisions to prepare for the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic but the real test will depend on how fast the Australian economy can recover. Australia slipped into its first recession in three decades as the central bank reduced its key interest rate to an all-time low.

"If the economy bounces back soon, then [the banks] may surprise on the upside by reducing provisions and allowing that to come back to the bottom line," North said. "The reverse is also true, if the economic recovery falters and bad debts rise, so will provisions, and profits will fall."

Australian banks had reported gross impaired loans as a ratio of loans held at amortized cost of below 0.50% in their full fiscal-year reports. S&P Global Ratings said in a November 2020 report that it expects the banks' aggregate NPA ratio to reach 2.4% in fiscal 2021, compared with 1.0% in 2020 and 0.9% in 2019.

The number of financially distressed households and businesses are expected to rise as the government reduces its support. The number of deferred loans peaked at 803,281 in June 2020, though it fell below 300,000 in November, according to data from the Australian Banking Association. The value of the deferred loans by the seven largest banks also fell below A$100 billion from its peak of A$250 billion in June.

"The banking landscape is changing, and fast," North said.