S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

14 Jun, 2021

By Carolyn Duren and Ali Shayan Sikander

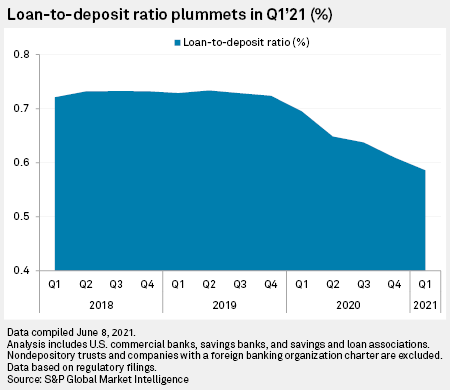

Loan-to-deposit ratios continue to fall at U.S. banks, as the economy has been bolstered by government stimulus and spending by both consumers and commercial entities has slowed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

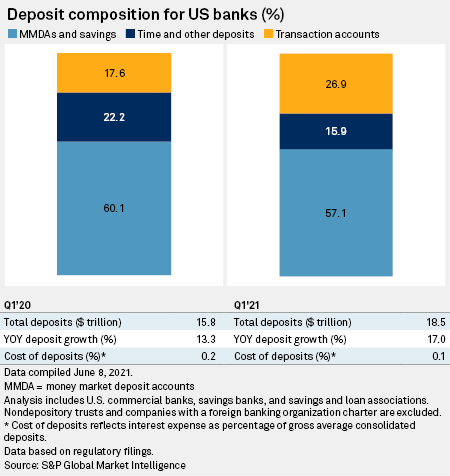

The aggregate loan-to-deposit ratio at U.S. banks has fallen every quarter since the second quarter of 2019. The ratio reached its lowest level in four years in the first quarter of 2021 at just 58.6%. The ratio is affected by both low loan growth and high deposit growth, and can be troublesome for banks' margins. A lack of lending to match deposit growth can lead to lower interest income and higher costs for banks to pay on deposits.

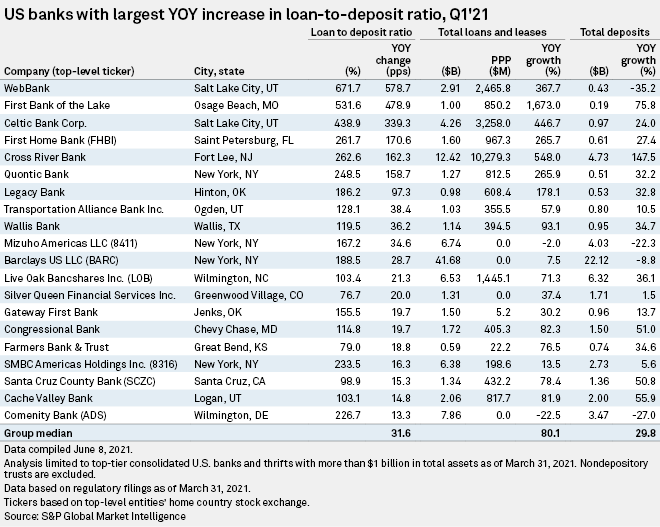

Some banks have seen growth in loan-to-deposit ratios, particularly those that are concentrated in Paycheck Protection Program lending. Salt Lake City, Utah-based WebBank saw its loan-to-deposit ratio increase 578.7 percentage points year over year in the first quarter. The bank reported $2.47 billion in PPP loans outstanding as of March 31, or about 85% of the bank's total loans.

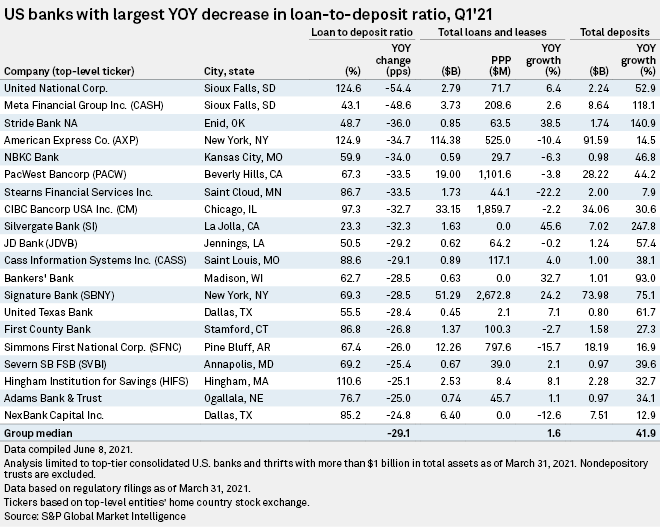

But even some banks that have been able to increase lending have seen such an increase in deposits that they are unable to maintain higher ratios. For La Jolla, Calif.-based Silvergate Bank, a 45.6% increase in loans year over year was far surpassed by a 247.8% increase in deposits, resulting in a drop of 32.3 percentage points in the bank's ratio.

Sioux Falls, S.D.-based United National Corp., which saw the largest decrease among banks with more than $1 billion in total assets, grew loans by 6.4%, but deposits grew 52.9%.

"Deposit growth has been significant," said Lindsey Piegza, chief economist at Stifel Financial Corp., in an interview. Piegza anticipates deposits will start to decrease as the economy opens up and consumers resume discretionary spending and the government stimulus comes to an end.

But loans could be slower to recover, Piegza said. She expects the economy will take all or most of 2022 to recover, and lending growth could be pushed out as far as 2023 or beyond.

Although interest rates are low and now would be a good time to borrow, businesses have been hesitant to take out loans in an environment still defined by pandemic uncertainty.

"No telling where exactly consumers will return first, if at all," Piegza said. "Some of these changes in spending patterns may be semi or entirely permanent."

"The uncertainty right now in the marketplace is far exceeding the very accommodative policies, or very easy money policies that are out there right now," Piegza said.

Excess liquidity at businesses may also be weighing down loan growth, said Christopher Marinac, head of research at Janney Montgomery Scott. When the pandemic first began there was a "massive dash" for liquidity, Marinac said, and now many companies are finding they have too much. "There's no reason to be a net borrower," he said.

Low interest rates, while good for potential borrowers, can weigh on banks' margins. Piegza said it is unlikely interest rates would increase prior to 2023, given what the Federal Reserve has signaled so far regarding a taper in its monthly bond purchases prior to the first rate increase.

"There is no sort of ticking time bomb here that the Fed has to raise rates any time now. They're going to be extremely patient, extremely deliberate," Piegza said.

Overall, both Marinac and Piegza said it is going to be a slow process for banks to change loan-to-deposit ratios and improve margins.

"It's going to be hard to see something meaningful for at least a year, maybe longer," said Marinac.