Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

27 Jan, 2021

By Jacob Holzman and Bill Holland

|

U.S. President Joe Biden prepares to sign a series of executive orders at the Resolute Desk in the Oval Office hours after his inauguration Jan. 20, 2021, in Washington, D.C. |

Much like the last time Democrats took control of the White House, President Joe Biden may find himself needing to support increased access to a controversial resource to achieve key policy goals.

For former President Barack Obama, that resource was natural gas — a pivotal part of shifting the U.S. power sector away from coal-fired generation and to curb the sector's greenhouse gas emissions. For Biden, mined battery metals will likely be needed to accomplish signature climate policies, such as mass deployment of electric vehicles.

Federal mineral mining financing has already been freed up by the outgoing Trump administration, the prospects of green stimulus appear poised to ratchet up demand for mined materials, and environmental permitting for mining looks unlikely to change.

With that setup, the Biden administration could take a leaf out of Obama's book, presiding over the blossoming of a policy-critical sector in part by simply not restricting it.

Biden already signaled Jan. 25 that mining will be key to his "Build Back Better" initiative when an executive order mandating government agencies to "buy American" included a call to maximize purchases of materials mined in the U.S.

History as a guide?

Mining executives worried about more restrictive regulation or strident environmental reviews under Biden could look at the Obama administration's approach to hydraulic fracking and natural gas production for some hints at a possible future.

"Draconian interventions were not in the Obama administration's interest," said Kevin Book, an energy policy analyst with Washington, D.C.-based ClearView Energy Partners LLC. "They regulated prudently in a limited rather than a maximal fashion. ... Barack Obama didn't come to Washington to be the oil president; he came to actually bring an energy transformation into force, and he got transformed by oil and gas. The ability to get where he wanted to go on green energy — it didn't exist."

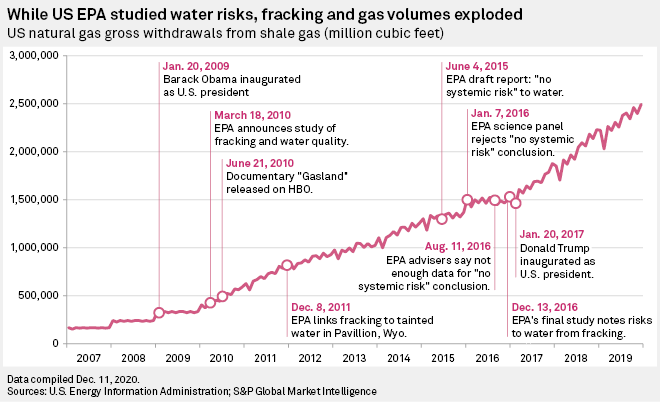

From start to finish, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's study of one facet of fracking — its potential threat to drinking water — took nearly six years and produced no real change in federal regulation of oil and gas fracking. As the shale boom gained steam, many raised concerns that the practice of injecting a cocktail of chemicals into the ground under high pressure represented a risk to drinking water supplies.

|

Public hearings in advance of the EPA study's design showed sharply divided communities. Torn between quick cash from lease bonuses and production royalties and a lack of reliable information on fracking, neighbors in shale country praised and protested, in equal measure, the sea change occurring across their land.

EPA administrators repeatedly expressed concerns about the unknowns of fracking as their investigators reported tainted water discoveries near gas fields from Pavillion, Wyo., to Dimock, Pa. Still, Obama praised natural gas as the fuel of the future in several State of the Union speeches while natural gas production from shale wells quintupled. Even though New York banned fracking, Obama got the gas he needed to crush coal as a fuel for power while reducing U.S. carbon dioxide emissions.

No significant new federal regulations governing fracking and drinking water were developed.

Fracking was not wholly uninhibited under the last Democratic White House. The Obama administration did issue new regulations on fracking on federal lands as well as rules on handling radioactive nuclides in drilling waste and total dissolved solids, ClearView's Book noted.

And the EPA approach may be more complex than Obama's trading cleaner fuel and job growth for a relatively hands-off approach on fracking and drinking water, Book added.

"Yes, he needed a lot more from the gas than the Clean Power Plan. He needed the economic output from all those jobs," Book said in an interview. "The EPA's job is not to create jobs. The EPA's job is to look at this stuff seriously. And the problem that they had was that there was so much poor information."

Permitting's place

Biden has pledged to curtail emissions from the fossil fuels sector, but he has said little about how he would regulate mining. At the same time, Biden's priorities of infrastructure and renewables funding should fit hand-in-glove with the mining industry, which is already adopting his "Build Back Better" campaign refrain.

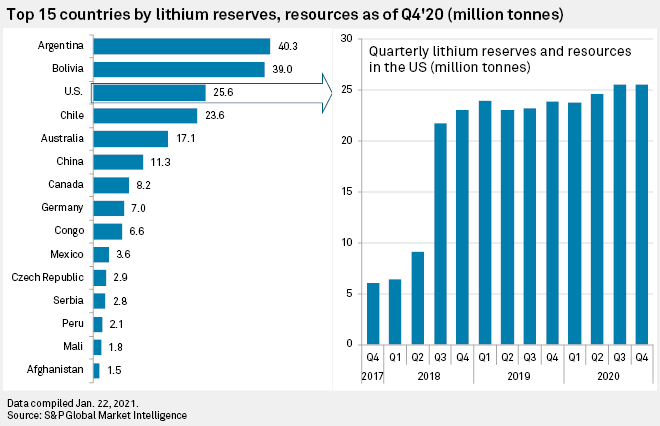

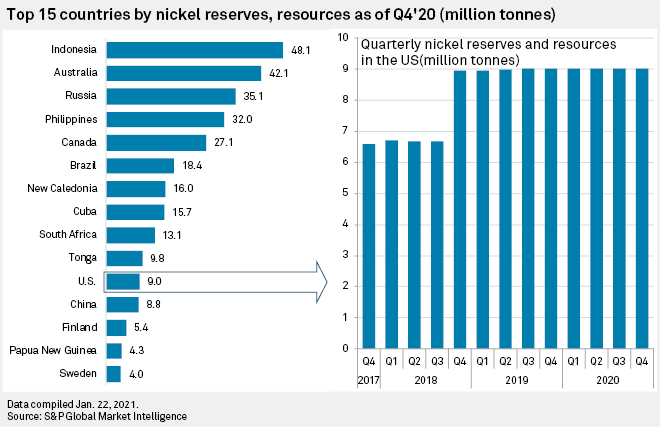

As demand for electric vehicles accelerates, so too will the need for minerals common in manufacturing lithium-ion battery packs, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper and graphite. In cases such as lithium and cobalt, supply of these raw materials has been concentrated among a few suppliers outside of the U.S., including China. Investment in new production could be necessary for the U.S. to overtake China as a top battery supplier, according to BloombergNEF.

Historically, mining in the U.S. has faced political opposition from environmental activists, much like the oil and gas space. Concerns over potential water pollution from mining and the impacts to sacred Native lands have been flashpoints in developing major mine projects on federal lands.

To date, federal policymakers in the Democratic Party focused on hard-rock mining have primarily spent their energy on opposing individual mining projects and overhauling the nation's mining laws, which have not been updated since 1872.

Miners under Trump saw victory in the overhaul of federal environmental permitting, a process they had long bemoaned as overly cumbersome and a cause for project delays and financing woes.

But Trump did not bring about a noticeable uptick in actual mines approved by the federal government, and Biden, in a similar fashion, is unlikely to impact permitting in any direction, BloombergNEF analyst Sharon Mustri said in a Jan. 14 interview.

"There is this narrative that Trump was going to ease environmental assessments and make permitting faster in the U.S. From my point of view, I haven't seen that have actually a big effect on the mining industry," Mustri said. "Honestly, I don't see that changing with Biden. I don't see it improving, but I don't see it worsening. I'm pretty sure it'll just stay the same from a federal point of view."

Resources rather than rules

One key difference between fracking and mining is that most regulation of oil and gas drilling occurs at the state level, while mines are often planned on federal real estate, requiring a more active role from the federal government.

Given that, the federal path to enabling key types of mining would likely look different than that for oil and gas.

The Biden administration may make federal money available to mining companies involved in supplying raw materials for the energy transition. The U.S. Energy Department under Trump recently expanded two Obama-era clean energy financing programs to permit mining companies and firms in the midstream of battery supply, such as cathode and anode manufacturers, to apply for government loans.

Faced with difficult cost hurdles, U.S. miners of battery metals are increasingly turning to the government for financial support to help them through the lengthy mine development process.

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence Managing Director Simon Moores expects that U.S. mining for "strategic raw materials and critical minerals" could blossom under Biden — much as fracking did under Obama — despite an expectation of "really stringent environmental assessments."

"You've got rare earths, that's a well-run story in D.C., [and] the key raw materials that go into lithium-ion batteries. Lithium, cobalt, graphite, manganese ... You've got to have a domestic supply base and build domestic knowledge of these critical minerals and materials," Moores said.

If Biden maintained the DOE financing program, for example, it would allow Biden to provide "instant and available loan money ... to get the supply chain up and running," Moores said.

One of the groups urging the Biden administration to make more funding and tax incentives available for the battery supply chain is the Zero Emission Transportation Association, an industry coalition formed in November 2020 of electric vehicle manufacturers, utilities, midstream manufacturers, and mining companies such as Albemarle Corp., Piedmont Lithium Ltd. and Lithium Americas Corp. The group advocates for policies intended to steer the U.S. toward 100% of auto sales as electric vehicles by 2030.

The association has privately urged Biden's staff to maintain Trump's changes to the DOE clean energy loan programs, Executive Director Joe Britton told S&P Global Market Intelligence.

"Our members, they're looking for help on the financing side, de-risking projects," Britton said. "We think there are ways the federal government can incentivize and support production through loan guarantees and other things ... for folks that are at that early stage and are ready to scale."

A spokesperson for Albemarle said in a Jan. 21 statement that it is "still early days, but with a Biden administration there is a potential benefit from support for electrification and EVs."

"The U.S. has been slower than the rest of the world in embracing EVs and we would like to see the U.S. be more competitive. We are in support of government grants or other programs that drive more domestic manufacturing, job creation and economic welfare for an industry that is going to be very important for the U.S. going forward," the spokesperson said.